By Sam Nichols

Managing Editor

X&O Labs

Editor’s Note: This spring X&O Labs was invited out to Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, MI to get an up close look at the changes that are taking place under 1st year head coach PJ Fleck. Western’s staff, to a man, thanked us for our work in helping coaches and allowed us full access to their practice and staff afterwards. The story that emerged was different than the one I expected to write, but it is one that we can all learn from and has lessons we can all use in our own coaching starting today.

Editor’s Note: This spring X&O Labs was invited out to Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, MI to get an up close look at the changes that are taking place under 1st year head coach PJ Fleck. Western’s staff, to a man, thanked us for our work in helping coaches and allowed us full access to their practice and staff afterwards. The story that emerged was different than the one I expected to write, but it is one that we can all learn from and has lessons we can all use in our own coaching starting today.

What does a 32 year old, first time head coach choose to base his program on as he takes over an FBS program? Flashy offense? Blitzing Defense? Neither. Instead, PJ Fleck came into Western Michigan looking to find the root of the reason that recent teams had not lived up to their billing. After some research, he and his staff determined that the difference between winning and losing Western Michigan University is protecting the football.

The data tells the story. Over the past few years, WMU is 4 and 39 when they lose the turnover margin. Conversely, the Broncos are 43 and 24 when winning that margin. Coach Fleck decided to take this idea and run with it, focusing all energies of his new staff on convincing their new team that “The Ball is the Program.” This refrain can be heard and seen throughout their practice and facilities and was the obvious focal point of the team during the practice that I viewed on April 29th. The concept was present in every individual, group, and team segment of their 24 period practice.

Defining “The Ball is the Program” Mentality

Coach Fleck made it very clear… controlling the ball is more than not fumbling or throwing interceptions. It is a mentality that every player needs to take personally and apply within his own position. For offensive players, this means holding on to the football, moving the chains, and even being in the right position to jump on the ball should it pop out. Defensively, the coaches impress the disciplines of what they call “ball disruption.” The spend time working on stripping the ball, batting it down, and scooping and scoring when the opportunity presents itself.

In addition to the reasons already stated, WMU’s coaches also acknowledged that their decision was a practical one for a first year staff. They said that ball security and ball disruption is a skill that is mostly a learned skill. That is to say that any player, regardless of talent level, can be taught these skills in a short time. This is important since they did not recruit any of the players they were working with this spring and there are talent deficiencies on their roster that can’t be addressed until later in the program building process. They believe that they can address those deficiencies by ensuring every player they put on the field can execute their ball security / disruption skills at a high level.

To get a better idea of how the WMU staff is implementing these skills with their players, I interviewed Bronco Offensive Coordinator Kirk Ciarrocca. Here is a transcript from that interview.

SN: Coach thanks for your willingness to share with us today. I love the concept of ball security / disruption I saw on the field today. Can you tell us where that all starts for you guys on the offensive side of the ball?

KC: Well the first thing for us is education. We need to educate the team on why it is so important. We talk to the guys about the connection of turnovers to wins. If I could look at only one stat to tell me who won a game, I would ask what the turnover margin was. We believe that it is the biggest predictor and the great thing is that it doesn’t have anything to do with ability level. We show them statistics to prove the concept and then impress it upon them that they have the ability to make an impact by focusing on ball security.

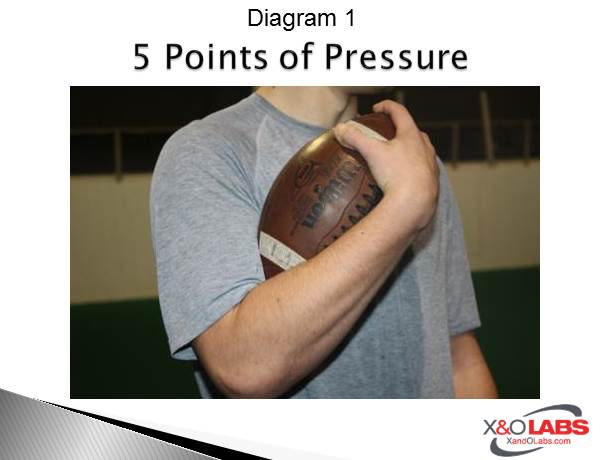

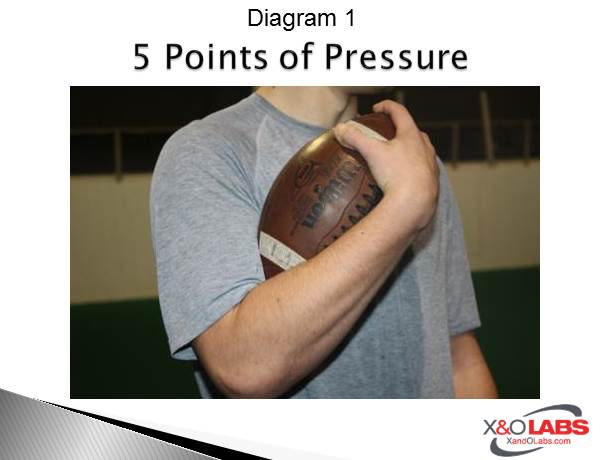

Once we have educated them on the concept as a whole, we can then move to teaching them the fundamentals. We teach the “chin” concept where the tip of the ball is tucked up under the runners chin. They also are expected to have 5 points of pressure on the ball at all times. 1 is the claw over the tip of the ball. 2 is the inside of the forearm. 3 is the tip of the ball under the bicep. 4 is pressing the ball against the peck and 5 is the elbow against the ribcage. We expect that at all times. It never leaves that position because the ball is the program.

Again this goes back to educating them. In our first team meeting, we show them how they are expected to carry the ball. From that moment on, all of our coaches will be on them to make it happen. We will chase them down the field to impress it on them. We are yelling “chin” all day long at our practices. Nothing else matters if we can’t take care of the ball.

SN: Yeah I heard that coach. It is obvious you guys really believe in the importance of this concept. What do you do in addition to yelling “chin” to teach the ball security basics?

KC: Well we certainly drill the concept. We have a ball security segment in every signel practice and we have a bunch of different drills we rotate through for players based on their positions. These range from fumble recovery to catching the ball and getting it to the chin position, to taking a handoff and getting it into the 5 points of pressure position. Again these change up every day and focus on different parts of the ball security concept. But really, it is about emphasis. We want to make it overwhelmingly clear that this is a priority for us and is essential if we are going to win games. We tell them it is the most important thing, so we have to show them that as well.

SN: So you have a variety of drills for each position that you use on a rotational basis I assume?

KC: Yes and of course we will change it up as needed to address problems. We are also willing to completely stop practice to address an issue in this area if it comes up. You saw that today. Coach Fleck saw a teaching moment with that fumble so he stopped the whole thing and impressed on the players the importance of holding on to the football and even scooping and scoring instead of jumping on the ball for the defense.

Coach Fleck tells us to forget about if a guy ran the route wrong, forget about his bad splits, and forget about his footwork on his handoff. If he doesn’t take care of the ball none of that other stuff matters. We cannot move on until we fix the ball security problems.

SN: Is this concept something you have done at your other stops at Rutgers or Delaware or is this something unique to what you guys are trying to do here at Western?

KC: Honestly it is something I have always focused on and something I am really proud of. Everywhere I have been we have made this a priority and we have seen success because of it. Conversely the teams that haven’t done well have not taken care of the ball. One year when I was at Delaware, we were 2-3 after 5 games because we weren’t taking care of the ball. We were able to turn it around and low and behold, we were protecting the ball better in the second half of that season. A lot of people talk about the importance of the big play or explosive plays on the outcome of the game, but we think that a lot of times that has to do with ability. Taking care of the ball, on the other hand, has nothing to do with talent or us calling the right play. It has everything to do with them respecting the ball and respecting the program. It was the same way when Coach Fleck and I were together at Rutgers.

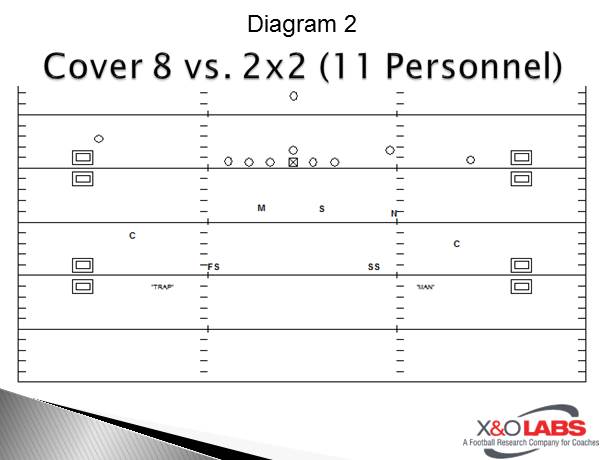

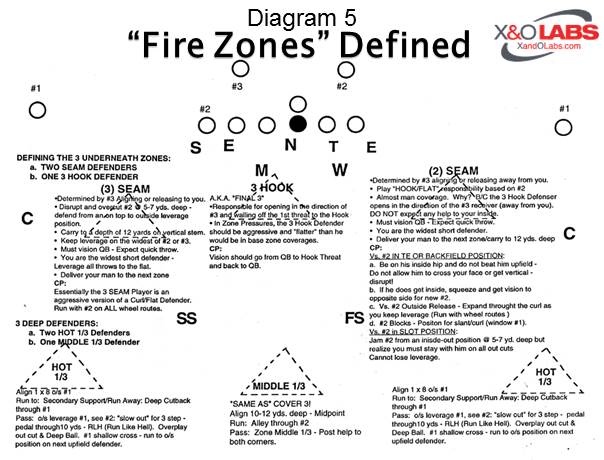

Editor’s Note: X&O Labs Senior Research Manager Mike Kuchar spent time this spring at Kean University (NJ) talking with head coach Dan Garrett and the rest of his defensive staff about the Cougars 50 front zone pressures. The Cougars finished 2nd in the NJCA in total defensive in 2012 and qualified for the Division 3 playoffs in 2011, the first in program history.

Editor’s Note: X&O Labs Senior Research Manager Mike Kuchar spent time this spring at Kean University (NJ) talking with head coach Dan Garrett and the rest of his defensive staff about the Cougars 50 front zone pressures. The Cougars finished 2nd in the NJCA in total defensive in 2012 and qualified for the Division 3 playoffs in 2011, the first in program history.

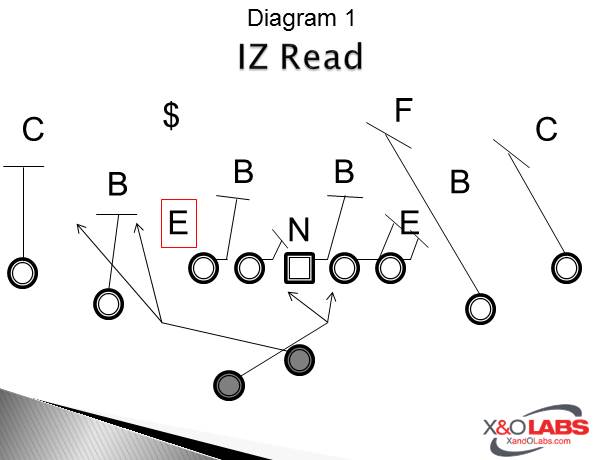

Editor’s Note: Herb Hand returns for a fourth year to the Commodore coaching staff as offensive line coach. This past season, the Commodores finished with a 9-4 record- one of the best in program history- including a bowl victory against NC State. Prior to accepting the Vanderbilt position, Hand worked three years at Tulsa, serving as assistant head coach, offensive coordinator and line coach. Hand helped guide Tulsa to consecutive GMAC Bowl appearances behind one of the NCAA’s most explosive spread offenses. Before joining Tulsa, Hand spent six successful years at West Virginia, serving as tight ends coach and recruiting coordinator under Coach Rich Rodriquez. Hand helped the Mountaineers to three Big East Conference titles and five straight postseason bowl games during the span, including a 38-35 victory over Southeastern Conference champion Georgia in the 2006 Sugar Bowl. X&O Labs Senior Research Manager Mike Kuchar spent some talking with Hand, who has been involved in spread systems since 1999.

Editor’s Note: Herb Hand returns for a fourth year to the Commodore coaching staff as offensive line coach. This past season, the Commodores finished with a 9-4 record- one of the best in program history- including a bowl victory against NC State. Prior to accepting the Vanderbilt position, Hand worked three years at Tulsa, serving as assistant head coach, offensive coordinator and line coach. Hand helped guide Tulsa to consecutive GMAC Bowl appearances behind one of the NCAA’s most explosive spread offenses. Before joining Tulsa, Hand spent six successful years at West Virginia, serving as tight ends coach and recruiting coordinator under Coach Rich Rodriquez. Hand helped the Mountaineers to three Big East Conference titles and five straight postseason bowl games during the span, including a 38-35 victory over Southeastern Conference champion Georgia in the 2006 Sugar Bowl. X&O Labs Senior Research Manager Mike Kuchar spent some talking with Hand, who has been involved in spread systems since 1999.

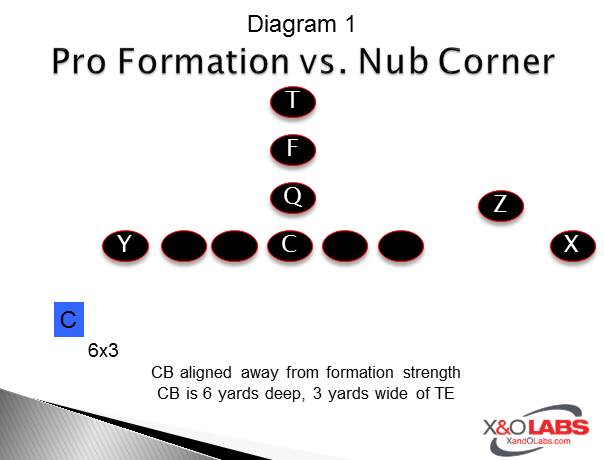

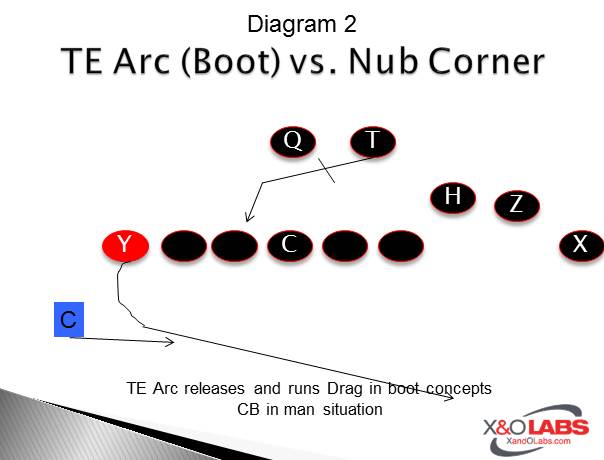

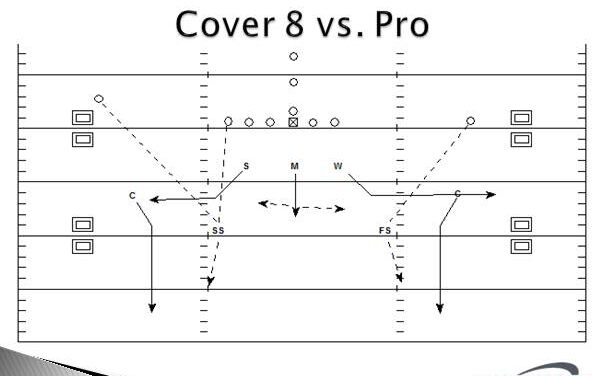

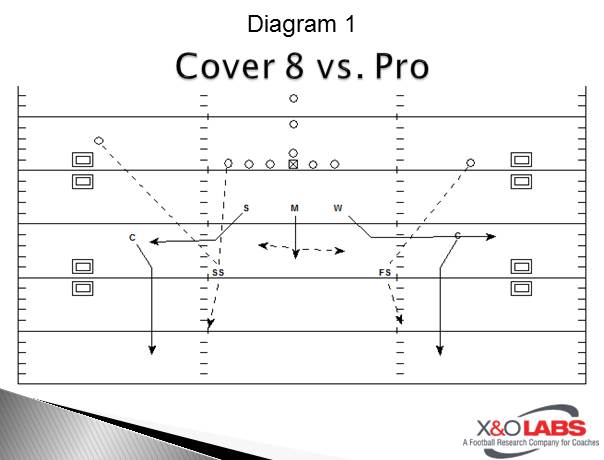

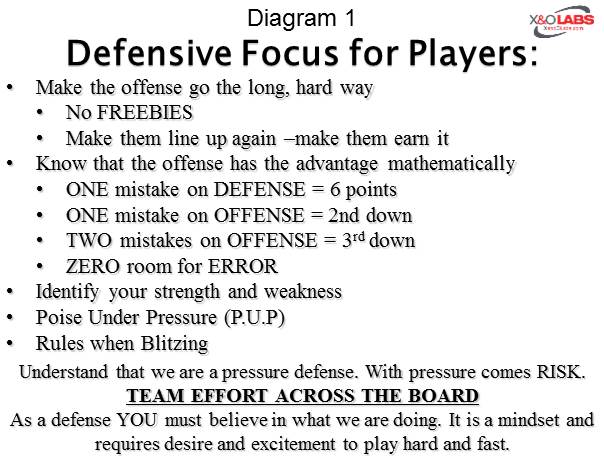

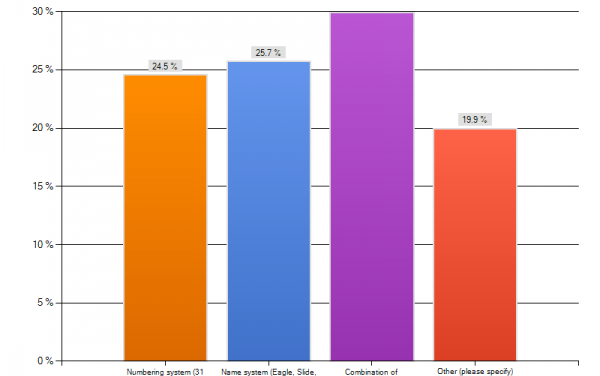

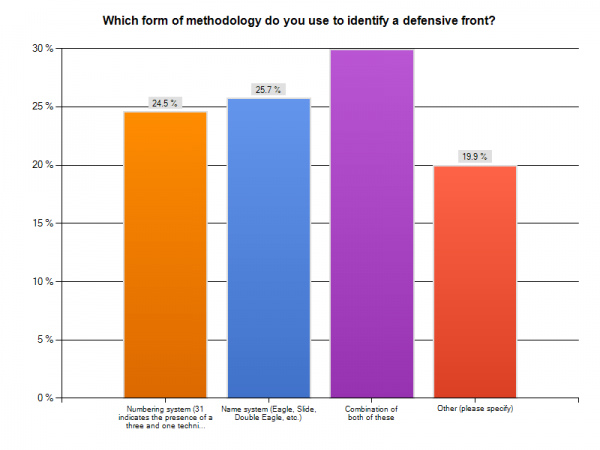

Bio: Mark Hendricks is currently the defensive coordinator at Lenape High School in New Jersey. Prior to his time at Lenape, Hendricks was the cornerbacks coach at James Madison University from 2008-2012. He was also the defensive coordinator at Rowan University (NJ) for a season.

Bio: Mark Hendricks is currently the defensive coordinator at Lenape High School in New Jersey. Prior to his time at Lenape, Hendricks was the cornerbacks coach at James Madison University from 2008-2012. He was also the defensive coordinator at Rowan University (NJ) for a season.