Best Available Blitzer (B.A.B.) Rules in Man Pressures

By Mike Kuchar with Brian Bergstrom

Head Coach

Winona State University (MN)

Twitter: @Coach_Bergy

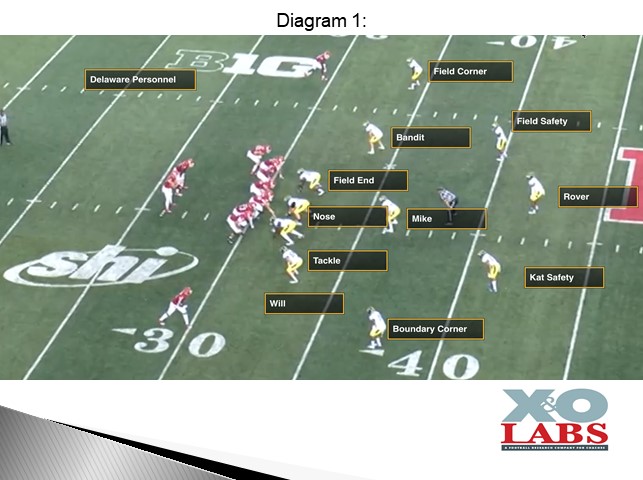

For several years, the South Dakota State University football program has been the prototype of a stingy defense at the FCS level. And former Jackrabbits co-defensive coordinator Brian Bergstrom served as the architect of that defense for five seasons, where he has been a part of five consecutive Jackrabbit playoff teams, earning three trips to the FCS national semifinals, including a runner-up finish.

And when he got his first head coaching job at Winona State University (MN) he wanted to take his four-down structure with him. But as he was installing his pressure package he came to a direct realization- he was overusing some of the three-deep, two-under pressures he relied on so often at SDSU. So, he shifted his philosophy to a simpler route- five and six man pressures, playing cover one behind them. It was for good reason, the movement up front was able to cancel gaps in the run game and if you’re getting into a pass situation, what better coverage to play than man?

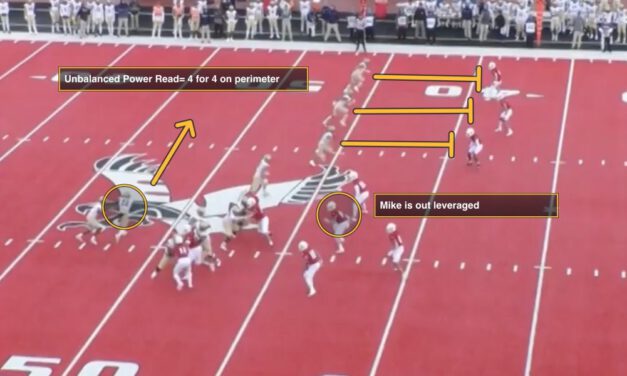

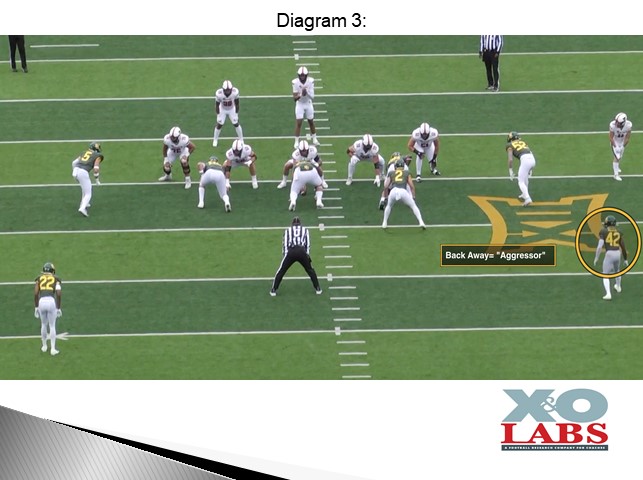

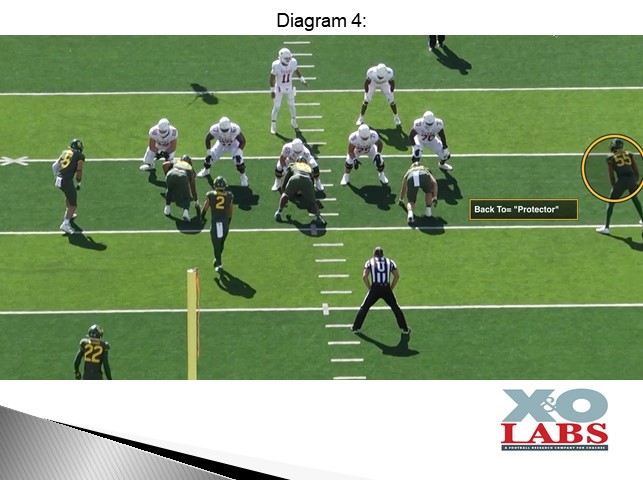

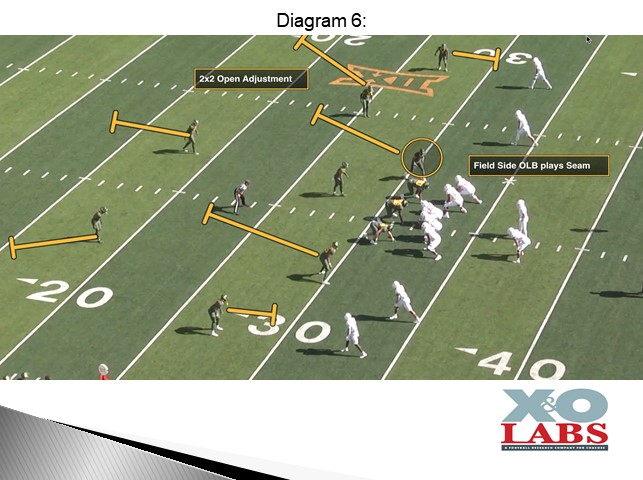

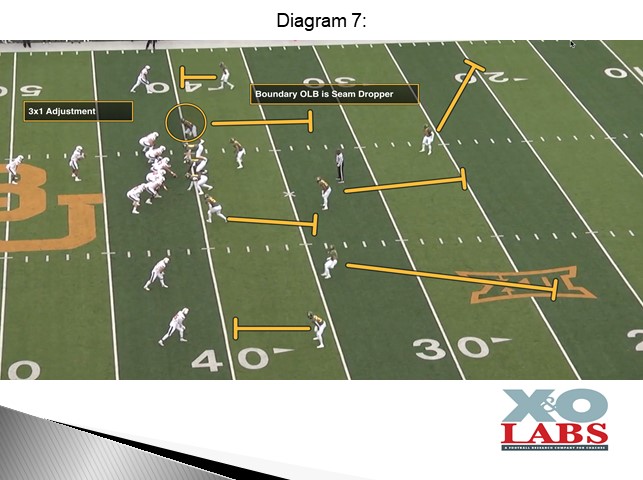

What’s unique about Coach Bergstrom’s system is that all of his man pressure concepts are adjustable by formation. He calls it “bringing the best available blitzer,” and it’s predicated by three types of pressures- field, boundary and interior. In this clinic report, we detail how these pressure is tagged, communicated and adjusted- based on front- in order to get free hitters home to the quarterback.

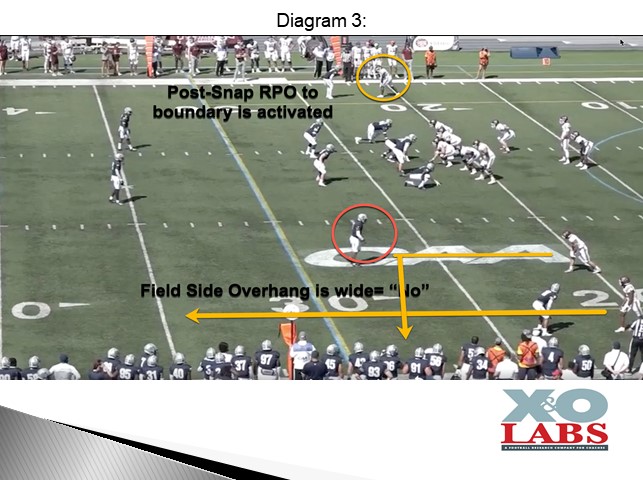

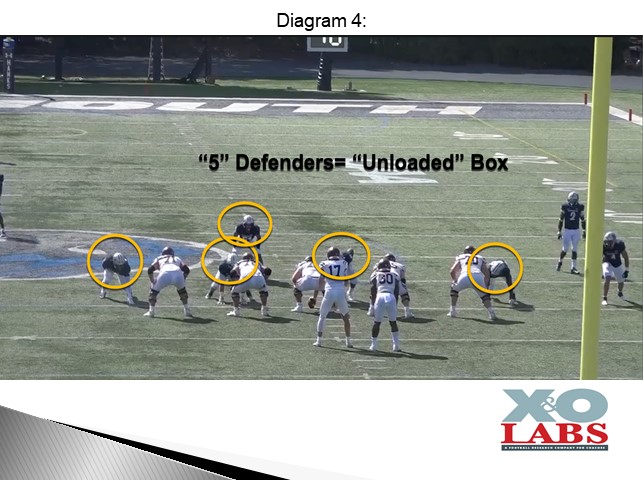

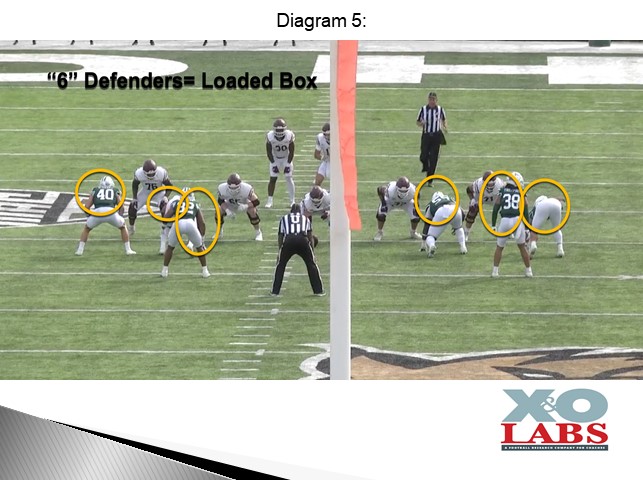

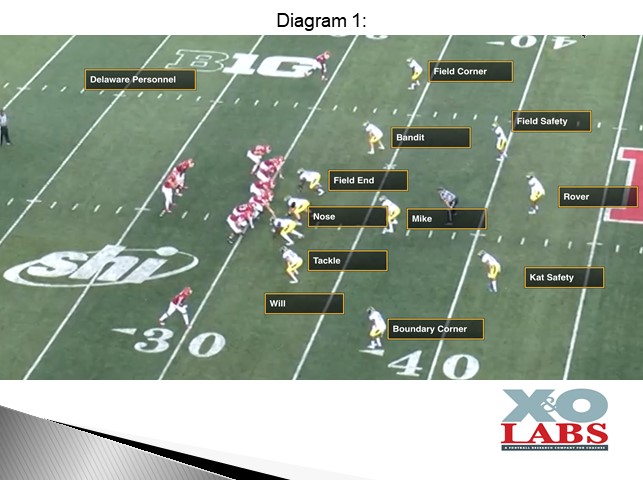

Base Rules:

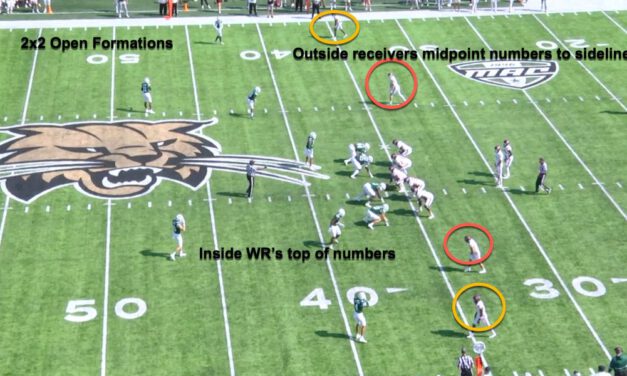

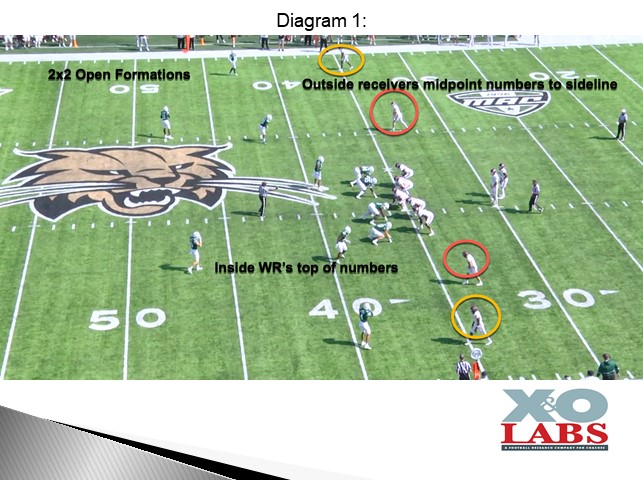

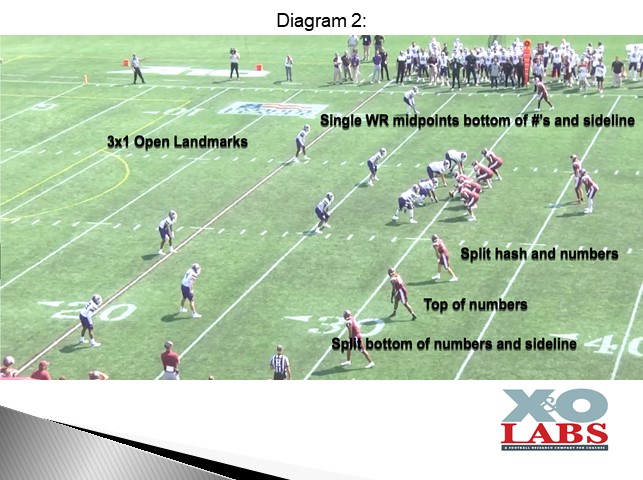

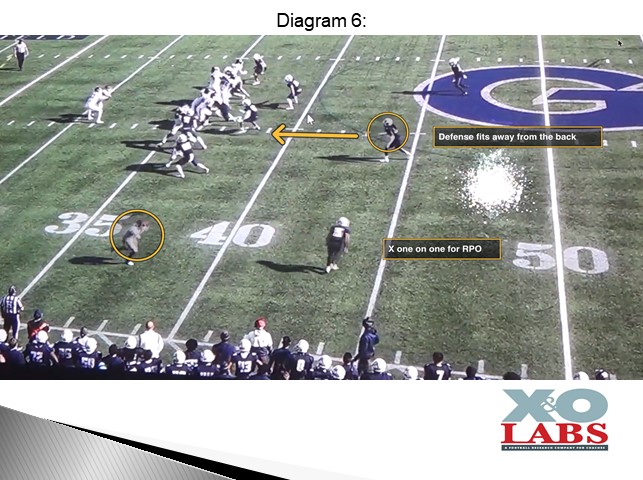

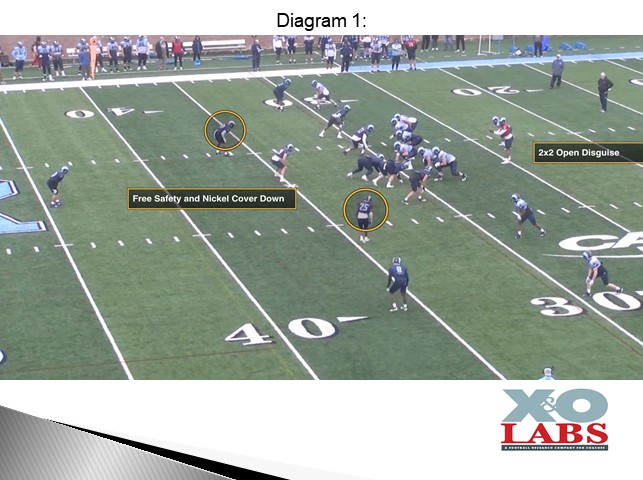

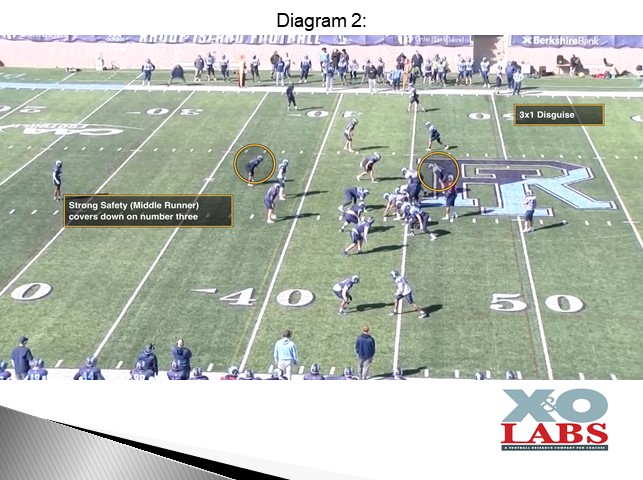

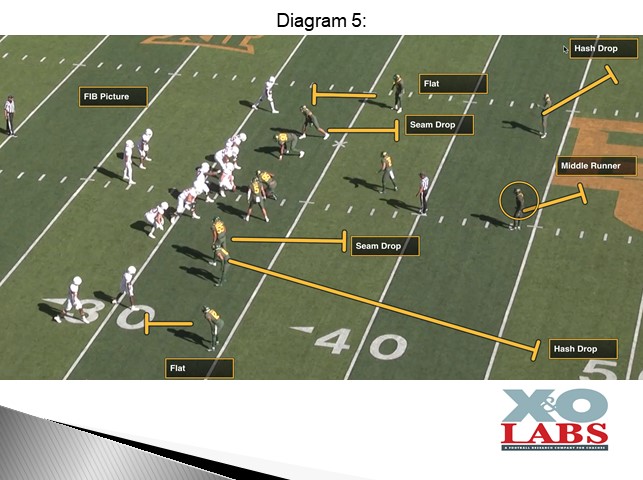

Essentially, Coach Bergstrom separates his pressures into the following: field pressures, boundary pressures and interior pressures. So, the activation will come from one of those three areas of the field. But instead of terming pressures with to denote who is blitzing (Will, Mike, etc.) he created a series of tags to alert defenders who is the rusher based on either offensive formation or personnel. It’s all categorized and taught first to non-blizers using the following progression.

Base Coverage Rules for Non-Blitzers:

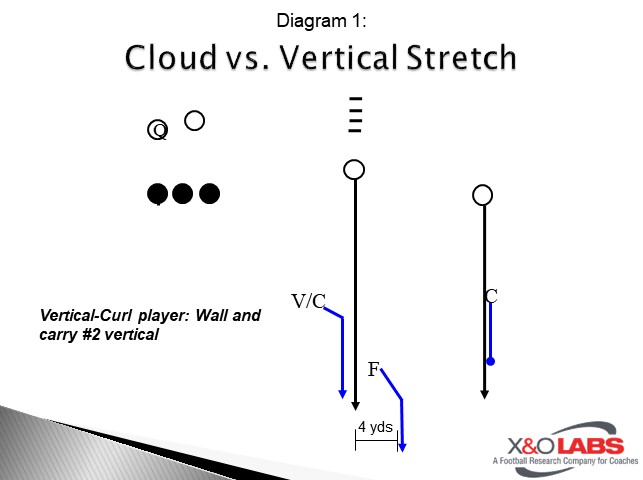

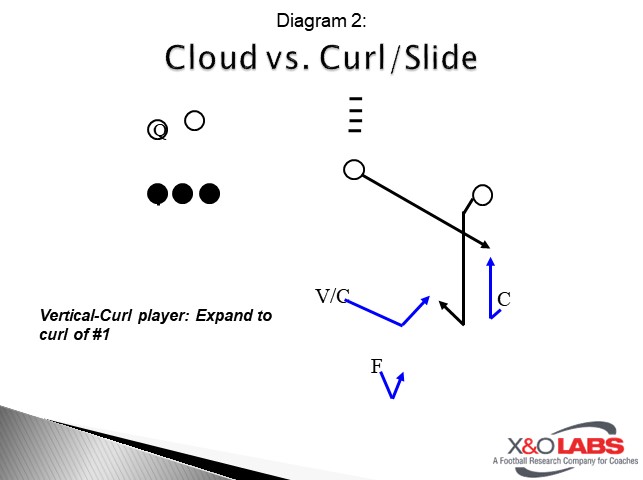

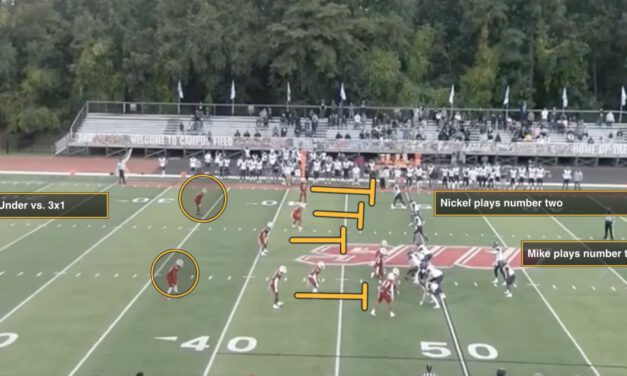

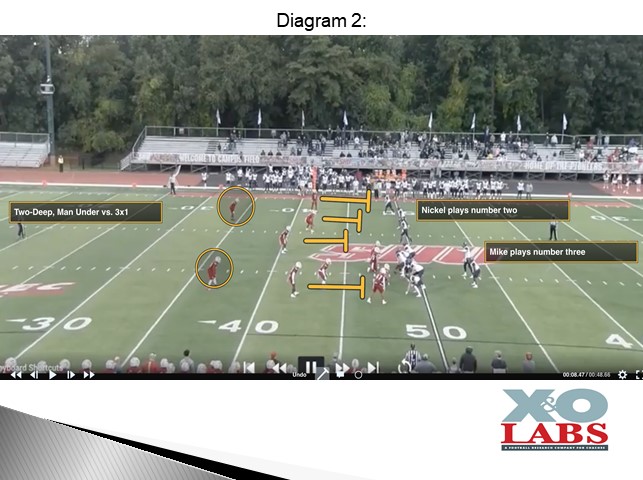

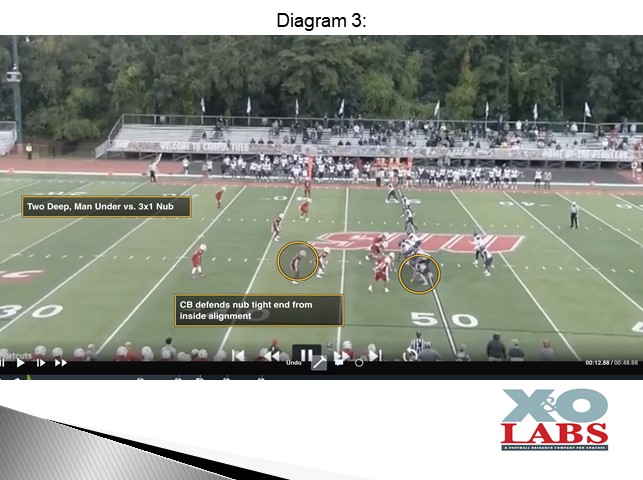

- If I’m a corner and I’m not blitzing, I cover number one

- If I’m a Sam or Nickel or Will and I’m not blitzing I cover number two

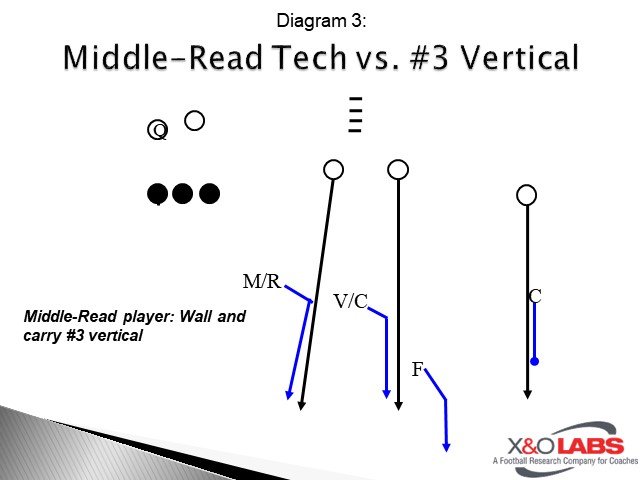

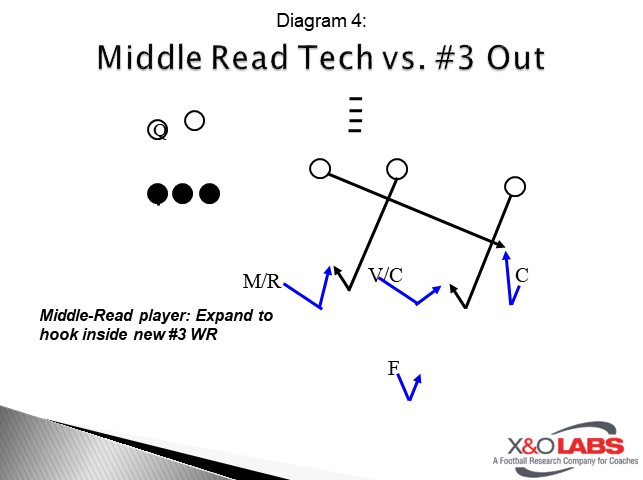

- If I’m a Mike and I’m not blitzing I cover number three

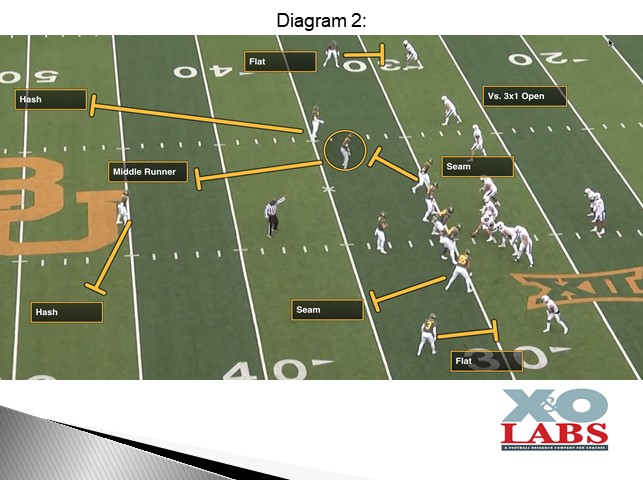

- Any three speed receivers to one side, Mike LB pressures

- Defensive end away from the pressure is usually responsible for the back if he flares. If not, he’s an additional rusher on the quarterback.

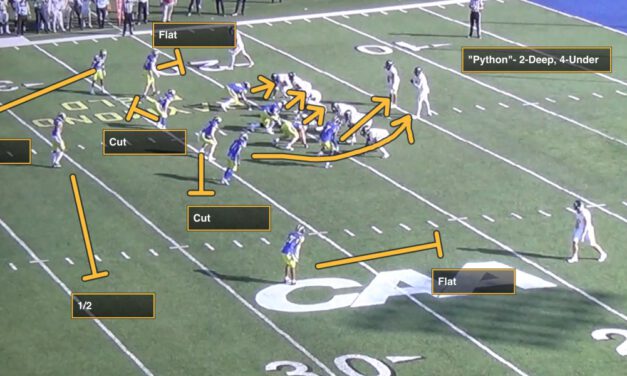

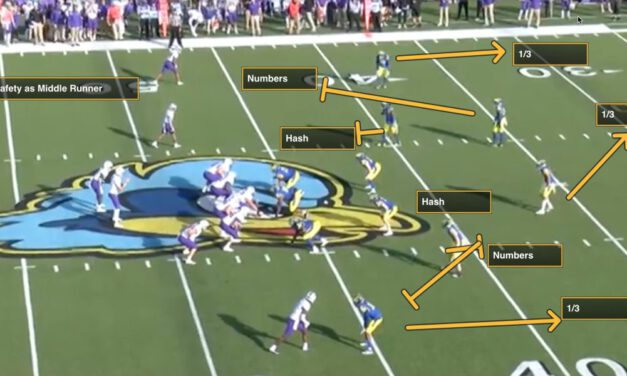

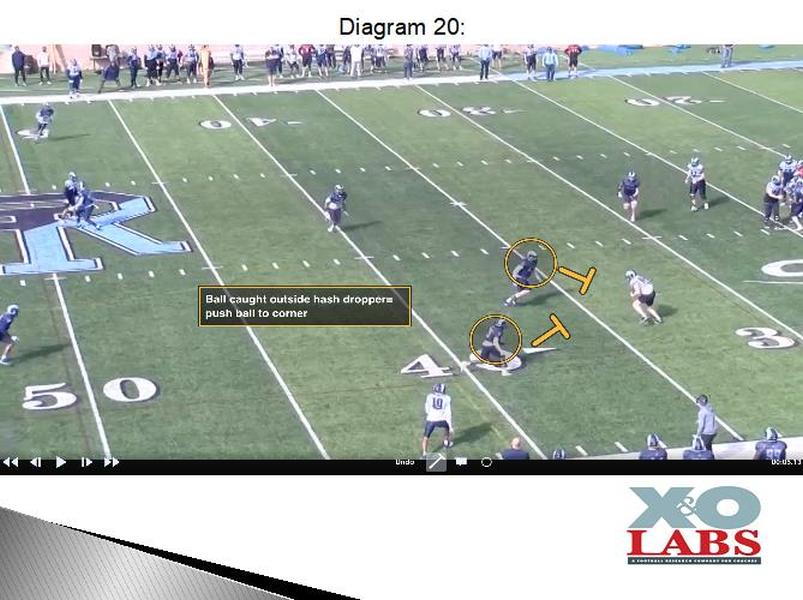

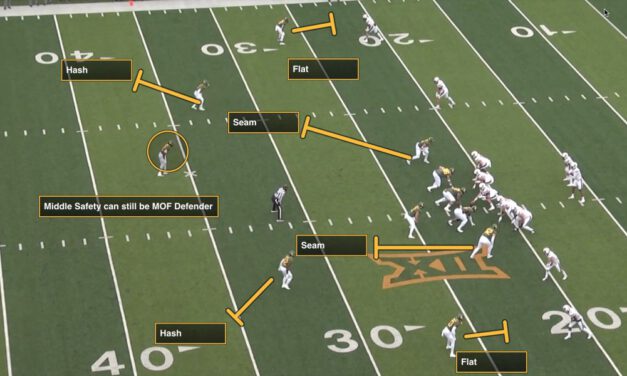

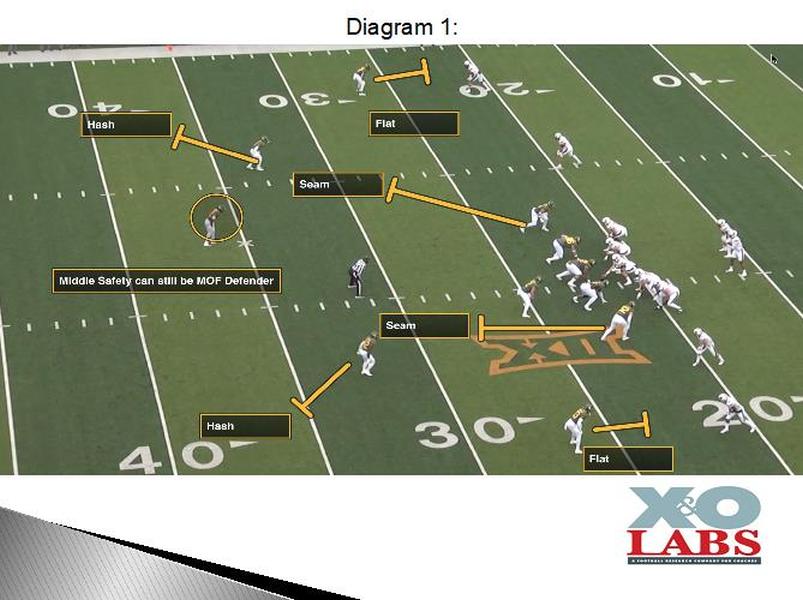

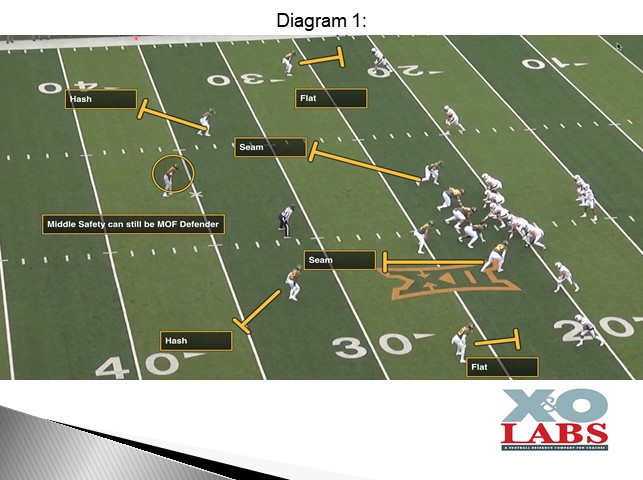

- Safeties need to know if they are spinning down to cover number two or are they working to middle third. If they are spinning down in a field pressure, they cover number two. If they are spinning down a middle pressure, they cover number three. If they are rotating to cover number one in a corner pressure, they use a slide and glide technique (referenced below).

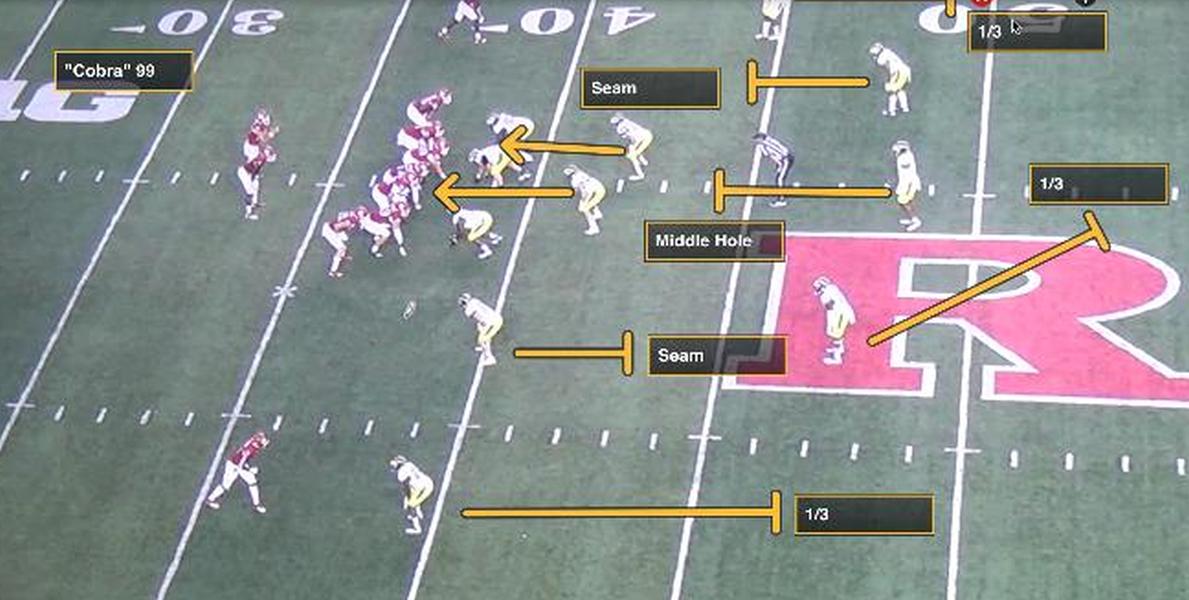

Tag System Rules:

The benefit of using field, boundary and interior tags is it makes options limitless for who can be involved in the pressure. “If you make the term generic for the pressure and tag it from where you want to bring it from that’s what makes it easy to teach,” said Coach Bergstrom. For example, if the pressure was called to the boundary and there was only one threat there, it becomes a cobra, or corner pressure and the defense plays by the coverage rules above. If there are two threats to the boundary, the Will and Mike can pressure, leaving the corner to play number one and the safety to play number two. “It’s not about the backer or corner always blitzing,” he said. “Sometimes there is an awkward surface for them to blitz from so we adjust by bringing someone else. We changed the code word of who is blitzing, and it helps against any mass shift of two or three guys moving so that we can reset it.”

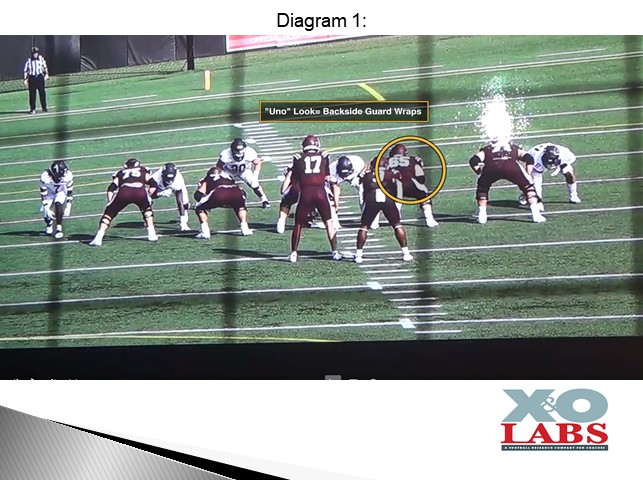

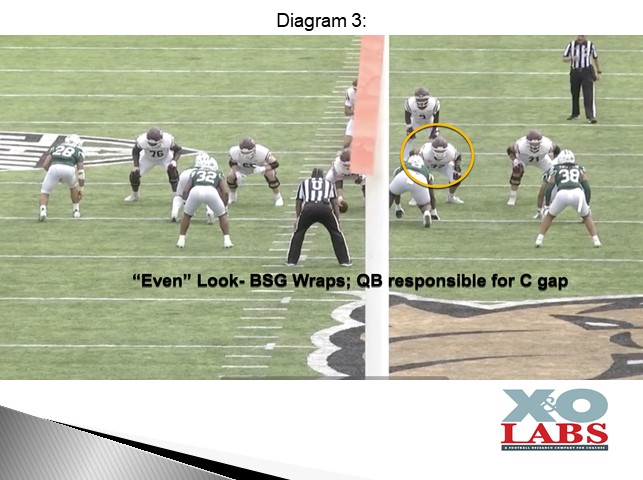

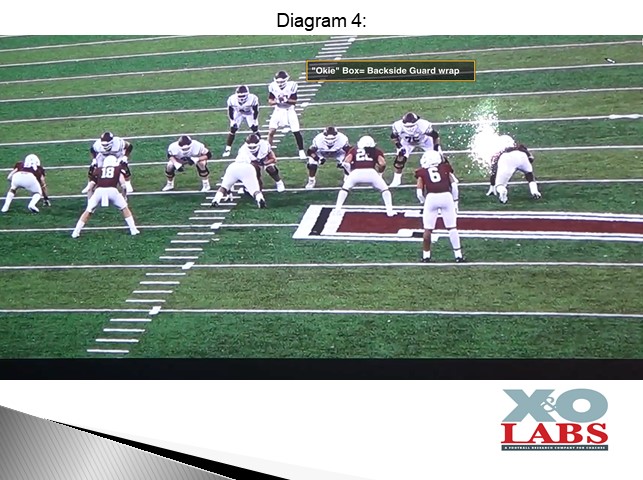

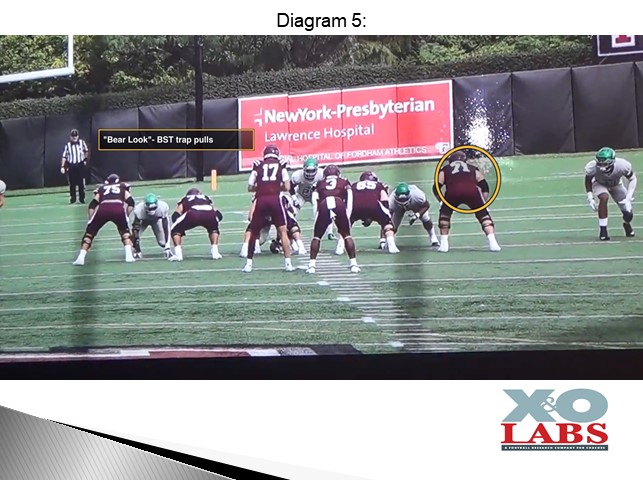

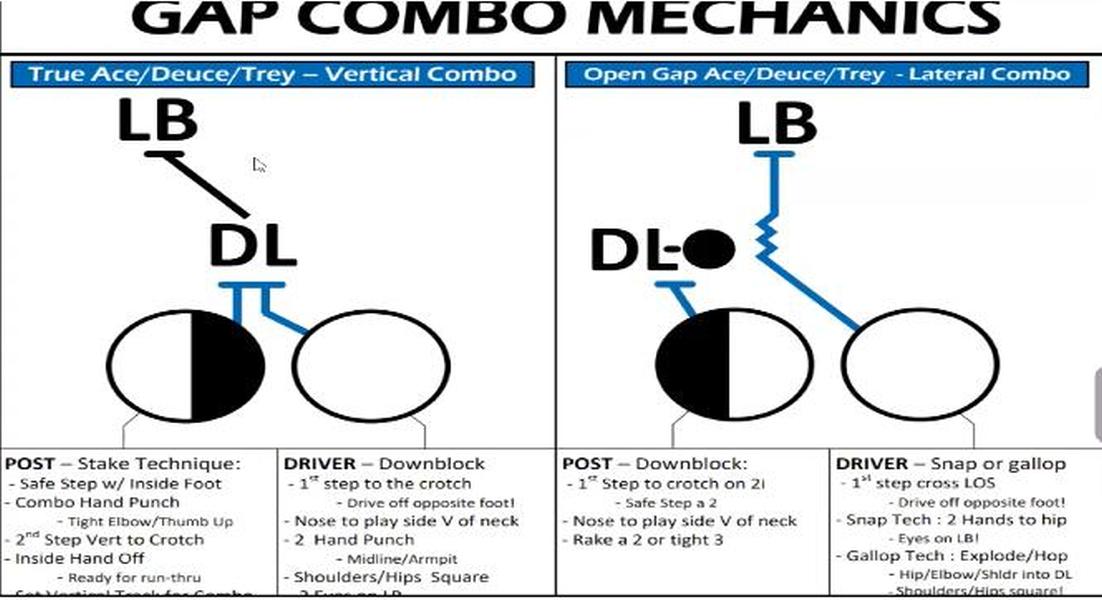

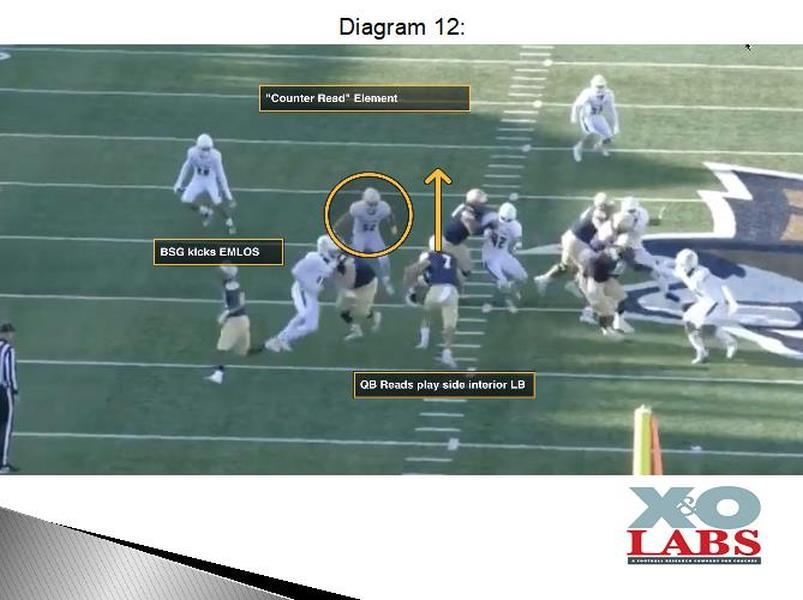

Base Pressure Rules:

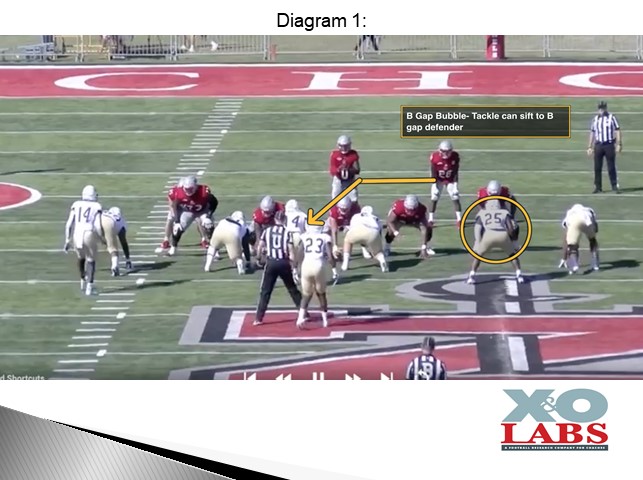

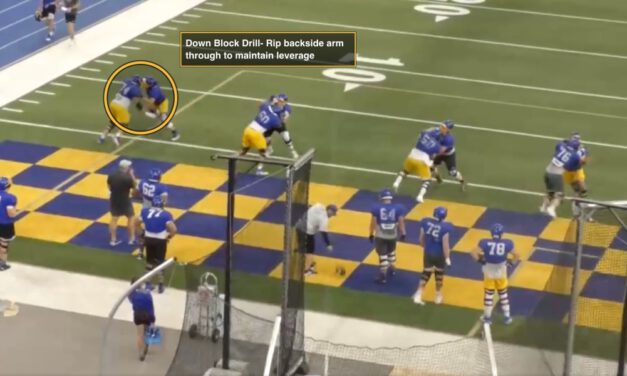

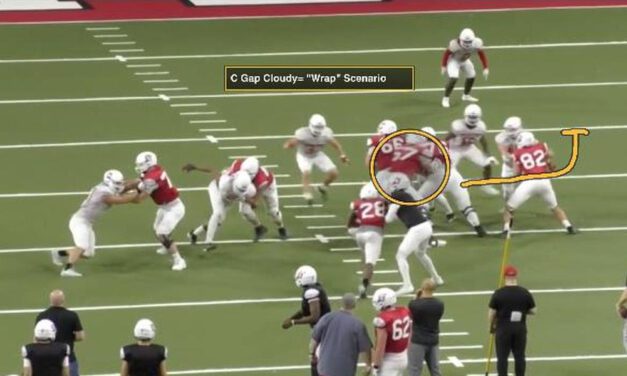

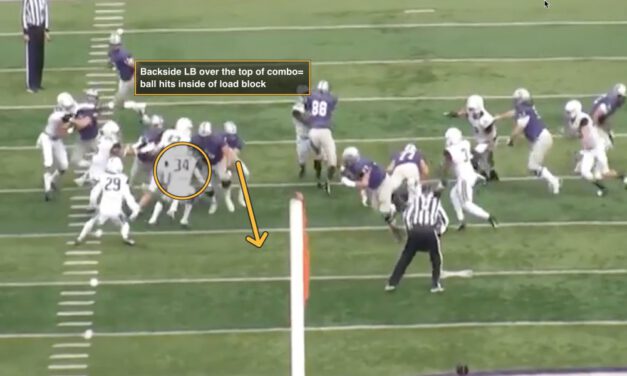

- Interior defensive lineman to pressure “rips across” Center’s face

- Exterior defensive lineman to pressure long sticks

- Interior defensive lineman away from pressure works to contain C gap

- Exterior defensive lineman away from pressure is responsible to peel on back

Now let’s look at how these rules are adapted into field, boundary and middle tagged pressures.