|

Player

|

Assignment

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

By Luis Hayes

Special Teams Coordinator

Long Beach Poly HS (CA)

Situational football, this is term that we coaches hear about all the time and incorporate it into our weekly preparation. As coaches there are countless situations that we all prepare for. During the season many teams script out situations so that they can see how well their team can execute their scheme in a specific game-like situation. This is true for most offensive and defensive coaches. Unfortunately, the one area of the game that often does not get to work situational football is special teams. This can be contributed to time factors and practice configuration. However, the one situation that no coordinator or head coach ever likes to been in is when you only have 10 men on the field. This is especially true in the kicking game. A special team’s coordinator nightmare is only having 10 men on the field and then having to explain to your head coach why you burned a timeout, took a penalty or were just flat out undisciplined. If you have ever coached special teams you may know exactly the feeling I are referring to. The question now is as a special team’s coach how do you prepare for those unique special teams situations?

As a special teams coach you must always be evaluating everything, specifically your personnel, scheme, and weekly preparation. These are three key factors that will enable your players to be successful on game day.

PLAYER EVALUATION

The evaluation of your players is something that a special teams coach should be doing year around. This is because a special team’s coordinator could potentially end up coaching every player on the roster before the season is over. Whether it’s the starting QB as your holder, your left tackle on PAT or the 9th string wide receiver who happens to also be your best long snapper. As the special coach you should know your roster better than anyone else and you should also be a great evaluator of each player’s individual talents. While many staffs debate about which offensive and defensive starters should and shouldn’t be allowed to play on special teams, the determining factor should always be effort. It is very easy to know who are the fastest or most athletic guys on your team but every coach needs to know which guy is incapable of playing more than one phase of the game. The evaluation of talent begins in the weight room. By evaluating your players in the weight room you will be able to predict how certain personnel will respond to certain situations. This will also help you to predict who you can and can’t count on in the kicking game.

Observing your players in adverse situations when they are fatigued will tell you whether they can play on special teams or not. When evaluating players it is very important to remain honest and objective about each player’s individual limitations. A player might have the biggest heart in the world but as a kid starts to exert himself past his mental or physical limits it is not only detrimental to the team to play him but it may also be detrimental to the safety of that player. Instead of riding your best players until they reach fatigue, play young talent that will take the field with fresh legs and enthusiasm. Special teams are an opportunity to get as many of your developmental or upcoming players involved in your program; it is not the part of the game where you want to push your best players to their limit because a mistake on special teams could cost you a game.

The other thing that any coach can evaluate about a player in weight room is responsibility. Our punt team consists of most responsible guys who were also the guys that never missed a lift, and never missed a practice. These are the type of guys that are purpose driven individuals and hard workers. Responsible athletes are also usually responsible students. This is the type of kid that you want to use on your special teams because they are mentally and physically dependable. They will keep their head in the game, know the situation, listen to the call and do their job. A lot of this information can also be gathered by looking at an athlete’s attendance at school and in the weight room or by just talking to your strength coaches. The ability to collaborate with the rest of your staff will make your special teams stronger and make managing your special teams easier.

SCHEME EVALUATION

Constantly evaluating your scheme will allow your players an opportunity to showcase their talent. The evaluation process begins by finding out what your players do best. Then as a coach you must be flexible enough to incorporate those skills into your scheme. For example, in 2011 we had 2 excellent kick returners, in fact both of which ended up returning kicks as true freshmen at their respective colleges; UCLA and Arizona St. My personal philosophy on kickoff return has always been to be a vertical downhill runner. The scheme that compliments this philosophy the best is double wedge however both of these return men were shifty elusive runners. For the first four games of the season I forced a scheme on these two seniors which also forced an unnatural running style on these athletes. Consequently, our double wedge return was average at best. However, after listening to my players and staff we added a sideline return that allowed our return guys to be an athlete and run in space. Needless to say our kickoff return became more explosive and dynamic. Conversely, in 2012 we had true vertical downhill runners, so we ran double wedge with great success.

By altering the scheme to fit our player’s talents we had much more success in the kicking game. We also had more guys willing to actively participate on our special teams and be genuinely excited about our kicking game because they were heard and valued as individuals. When the players are excited they look forward to the situation and this eliminates a lack of focus which also naturally makes them better prepared for all special teams situations. This all stems from knowing what our athletes do best, the ability to be flexible and to also allow our players to evaluate the scheme. I always keep in mind that the players have to execute the scheme with a maximum amount of effort and desire. By building off their strengths and providing each special teams unit with a certain level of autonomy and ownership they now have the ability to master the scheme and execute it with great success.

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

By Sam Nichols

Managing Editor

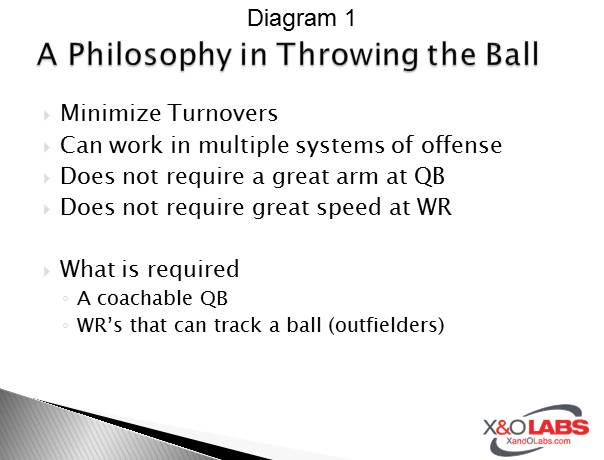

X&O Labs Editor’s Note: Perennial Division 2 Powerhouse Grand Valley State University was kind enough to invite X&O Labs Managing Editor out for an exclusive look at their practice. While there, GVSU’s Quarterback Coach Jack Ginn went into great detail on how they coach their quarterbacks and receivers to make explosive plays in the passing plays in unconventional, but highly effective ways. The following report includes an exclusive interview with Coach Ginn and an in-depth practice review that shows how GVSU has built its practices around its vertical passing attack.

Grand Valley has always been able to score points. Dating back to its emergence on to the national stage under now Notre Dame Head Coach Brian Kelly, they have done much of this scoring by pushing the ball downfield in the passing game. I have personally set through multiple clinic talks by Kelly and his successor and now Notre Dame Offensive Coordinator Chuck Martin where they detailed both the importance of throwing it vertical and the schemes they use in that part of the game. I was always amazed at how they were able to be so consistent in creating big plays with these relatively simple schemes. Grand Valley has always been able to score points. Dating back to its emergence on to the national stage under now Notre Dame Head Coach Brian Kelly, they have done much of this scoring by pushing the ball downfield in the passing game. I have personally set through multiple clinic talks by Kelly and his successor and now Notre Dame Offensive Coordinator Chuck Martin where they detailed both the importance of throwing it vertical and the schemes they use in that part of the game. I was always amazed at how they were able to be so consistent in creating big plays with these relatively simple schemes.

So the question is… how are they able to be ranked 5th in the country in passing efficiency in 2012 and 1st in 2011 if they are so focused on throwing vertically. That is what I set out to discover as I visited Grand Valley and sat down with their Quarterback Coach Jack Ginn.

Interview with Jack Ginn:

SN: Coach I know that you guys are big in throwing the ball down the field. Throughout practice today, you guys worked it deep and often. Give us an overview of how and why you guys do this so effectively.

Well here is what it all comes down to, we will always be throwing the ball away from the defense. For us, it is almost like a two play call or a read option. When we throw the vertical passes we think that if we are isolated one on one there is no covering our players. We will always throw it to space where our guy can get it. We encourage our guys to not run the play like it is on paper, but instead to throw it where they are not.

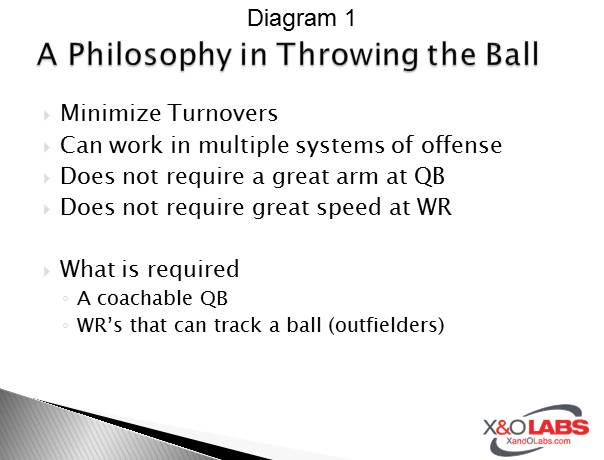

When we talk vertical passing game, we are working to get the ball to the outside of the field. The only exception, of course, is when the defense is in a 2 deep look. We recruit that as well. We want tall guys that can go up and get the ball down the field. We really think this works well because you don’t have to have a great arm or great speed to make it work. What you really need are guys who can track the ball. They need to have depth perception and need to be like outfielder.

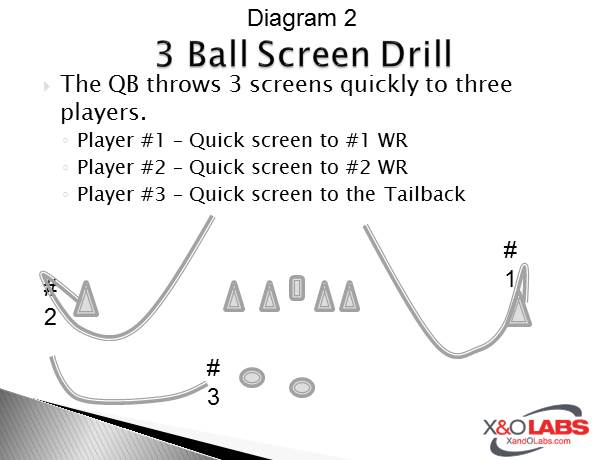

SN: How do you drill that stuff coach?

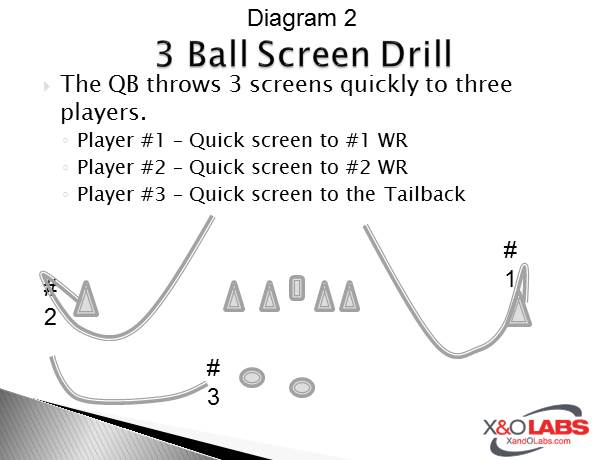

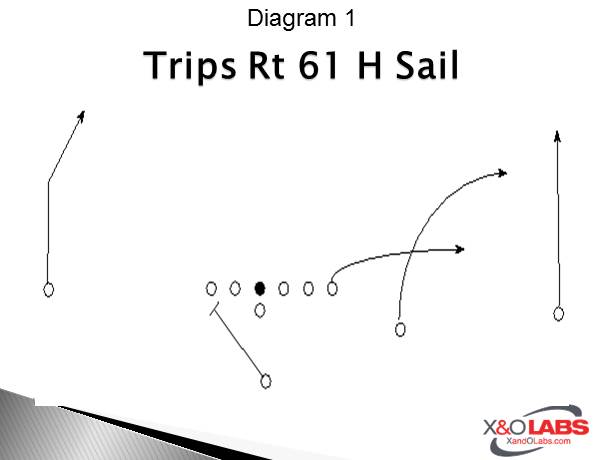

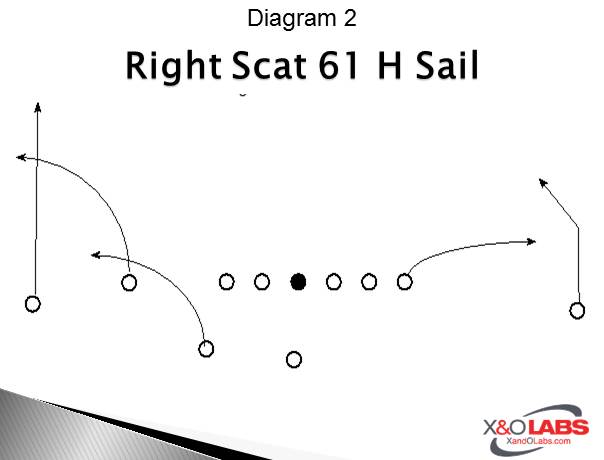

Well one drill we really like is to run our screens (diagram 2) and then follow it up with the go routes. Our players get so ingrained to the short outside throw that our DB’s start playing for it. At that point, it becomes a battle of wills as to who can be the shortest and most outside person on the deep balls. We counter that be moving from the short routes to working the go routes down the field with a focus on working to get vertical and beat someone. Don’t get me wrong, it is very rarely that we do blow by someone and run in open field, we don’t have a single guy running a 4.5. That said, we need our guys to work to it to allow the play and spacing to develop underneath.

So how do we go about getting the reps? Well it is simply what we do. We start pre-practice with go routes on air. The majority of our routes in 1 on 1 drills are go routes. We hang our hat on our ability to make those plays. If we can’t win the deep balls then we will not be able to control the pressure.

SN: So you guys really use the deep ball to set up the rest of your game and control how the defense tries to attack you. That makes sense coach. I saw that throughout practice. So what are you telling the quarterbacks as they are throwing these routes?

We tell them that they should either drop it on his head or throw it outside of him. But of course we can’t do that if the corner is outside. I explain by comparing this to a basketball player posting up in the lane. As long as the post player has the defender on his hip, then you lob the ball to the open space so he can go get it and win the 1 on 1 matchup. If the defender moves to a different position, they lob to a different spot. In our passing game, we never throw to a spot. We will always throw away from the defense even when it isn’t a vertical route.

Here is the thing that is interesting… In the history of Grand Valley is Brian Kelly came as the Defensive Coordinator, became the head coach, and then ran the offense. Same for Chuck Martin, came as the DC and became the OC when he became the head coach. Matt Mitchell, our current head coach, was the defensive coordinator and while he didn’t become the offensive coordinator when he became the head coach, he left the guys in place that had been running it so really our offense was built by defensive guys. They learned the game from the other side of the ball and applied it to their offensive philosophy.

SN: That is interesting coach. So if you are throwing to space, what are you teaching the quarterbacks to determine who is “open?”

Well here is a diagram we use to teach that concept (diagram 3 below). In the upper left you see a guy bracketed by 4 defenders. It is going to take a hell of a throw to get him the ball and have the ball not be toward any one of those people. If you take away one of those players (upper right) then we think we can get that guy the ball if we throw it where the defender was removed. Similarly, if you take away two of them (lower left), we then it almost becomes easy. If you take away three (lower right), then we have all sorts of options.

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

By William Mitchell

Head Coach

Lewisville High School (SC)

Watch a few games any weekend and you are bound to see an abundance of missed tackles. And just in case you don’t see them, the announcers will make sure to talk about how “bad tackling has gotten and how coaches just need to get back to the fundamentals if they want to win.” As a defensive coordinator for the past 12 years, I come at this from a completely different angle. I don’t necessarily believe that we (defensive coaches) have started to blow off fundamentals as much as it has to do with the changes in offensive schemes and overall team strength & conditioning.

Think about if for a second…Offensive football, whether it be Mike Leach’s Air Raid or Urban Meyer’s Spread Option or even Paul Johnson’s Double Wing, has become a game where the best coaches seek to create more one on one match-ups out in space. This requires the defensive players to make more one on one open-field tackles than before. In addition, athletes are becoming stronger & faster at the lower levels of football than they have ever been before.

And while these changes certainly do change the game is played, they haven’t always changed the ways that we prepare. In many ways, the traditional tackling drills that have been used for decades are not preparing our players to succeed in the modern game. They are more focused on “tackling in a phone booth” so to speak instead of making the player a better open-field tackler. Sure the old “Door Drill” and the “Eye-Opener Drill” certainly still have their place, but do they really help a player get ready to tackle Percy Harvin on the bubble screen?

For that reason, I go into every off-season looking for new drills that can specifically prepare my athletes to tackle in space. Ideally, these drills should be effective with or without pads so we can use them throughout the off-season yet translate well onto the field. Here are the two best drills that we use and that I believe can improve your teams open field tackling in a short amount of time. The first I learned from Tyrone Nix when he was at Ole Miss and the second I picked up from a Florida high school coach.

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

By Mike Kuchar

Senior Research Manager

X&O Labs

Coach Aranda comes to Utah State after four years at Hawai`i, the last two spent as the Warriors’ defensive coordinator after coaching UH’s defensive line the first two years. Last year’s Hawai`i defense led the Western Athletic Conference and was tied for 15th in the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) in sacks with 35 (2.7 pg), led by linebacker Art Laurel who ranked third in the WAC and tied for 24th in the nation with nine sacks. Coach Aranda comes to Utah State after four years at Hawai`i, the last two spent as the Warriors’ defensive coordinator after coaching UH’s defensive line the first two years. Last year’s Hawai`i defense led the Western Athletic Conference and was tied for 15th in the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) in sacks with 35 (2.7 pg), led by linebacker Art Laurel who ranked third in the WAC and tied for 24th in the nation with nine sacks.

As the defensive coordinator at the University of Hawaii last season, Dave Aranda would get his weekly dose of read zone schemes from teams such as the University of Nevada and Utah State University – which is ironically where he’ll call the defensive shots this season. So, he’d get frustrated at times watching offenses pre-determine who they were reading in the option game based on pre-snap alignment. Aranda, who runs a 4-3 base quarters package used to play single-gap control defense and wind up getting gashed for big yardage on zone wind backs because of a numbers advantage on the offense because of his two-safety look.

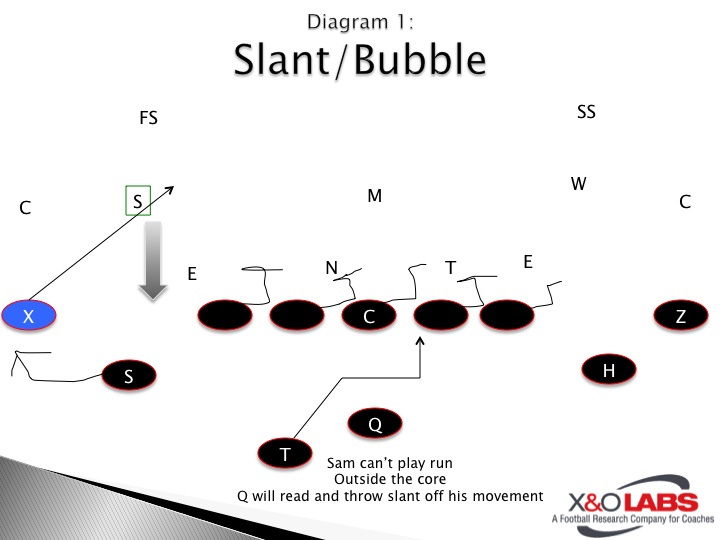

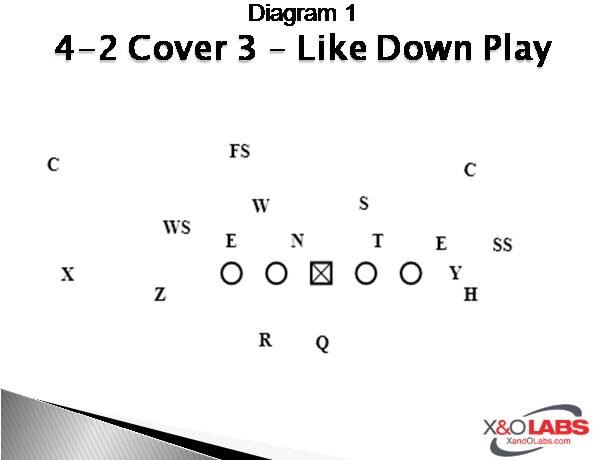

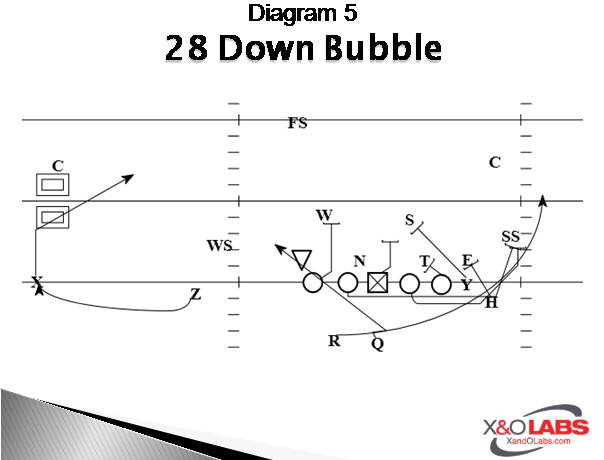

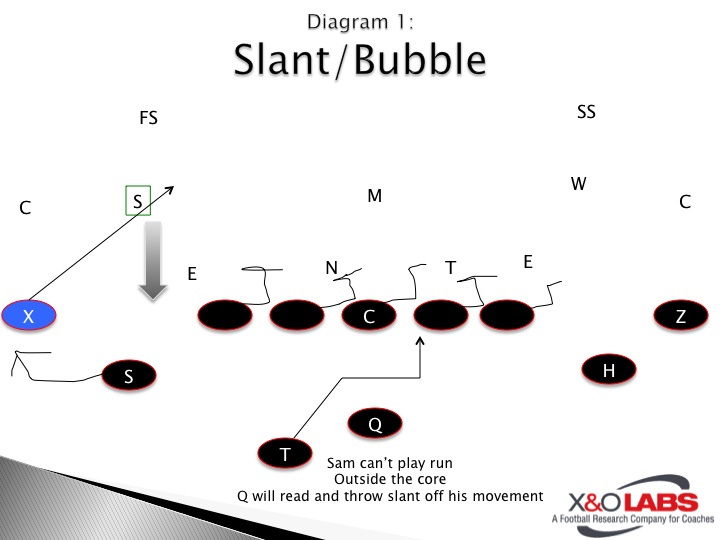

“No matter how you draw it up, the offense will have four guys at the point of attack – the QB, the tackle, the guard and the running back. If you’re a one gap type team and you’re playing it that way, whether your have a five and a 1-tech or a 3- and a 5-tech it really doesn’t matter because it’s four on three,” says Aranda. “You have two DL and one LB. The DE gets the shaft because he has to play two aspects – the dive, the bend of the dive to the inside out to the QB. You’re cheating a guy. An easy answer is to use someone from outside the box and bring him inside the box. The problem with that is the bubble screens and the now screens that are thrown by these offenses. Teams will read the LB that is walked out. If that LB steps up and reads run on the play action to handle QB on zone read. Once the QB sees him step up, he disconnects from the RB and throws the slant over the top of his head. It’s a tough play (diagram 1). I found you needed to get four and four and equate the numbers post-snap.”

So, after years of toiling with it, Aranda has changed to a more unconventional methodology when attacking the read zone schemes – and it comes in the name of equating numbers in the run game by two-gapping players across the board. Now, we must say it takes a ton of teaching, but if you see this across your schedule like Aranda did in the Mountain West Conference, it may be of interest to what you’re doing. He calls it getting “four-on-four” concept in the run game and like any other defensive preparation it starts with dissecting which kind of zone read team you are seeing.

“Zone” Read Teams vs. “Zeer” Read Teams

When Aranda starts prepping for a read zone team, he makes two vital distinctions. Are they a zone read team or a Zeer read team? Sounds like science fiction? It did to us, at least until he explained it.

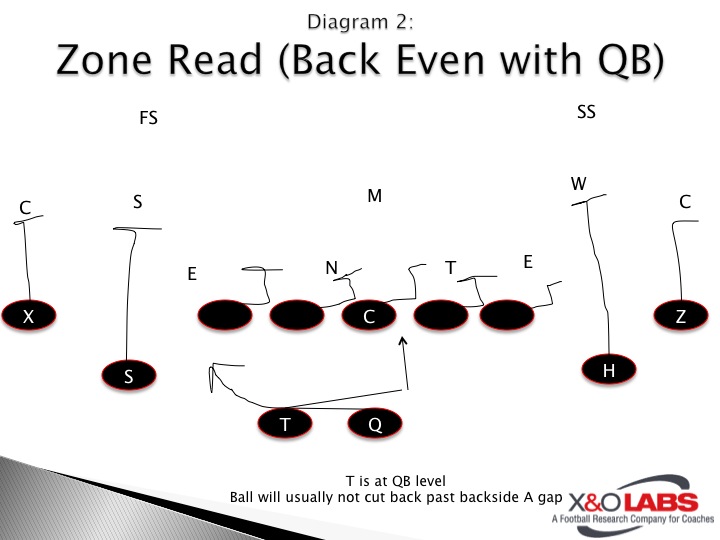

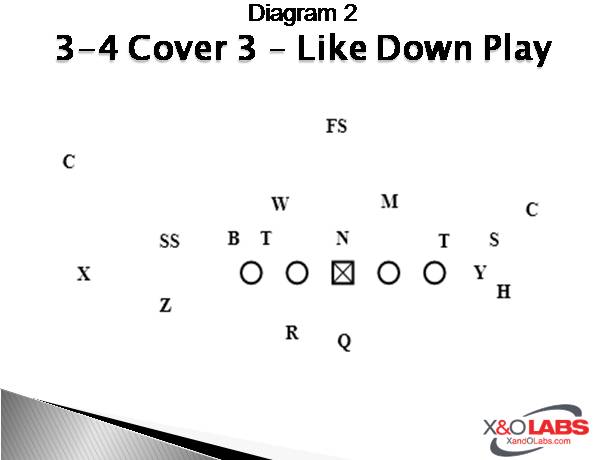

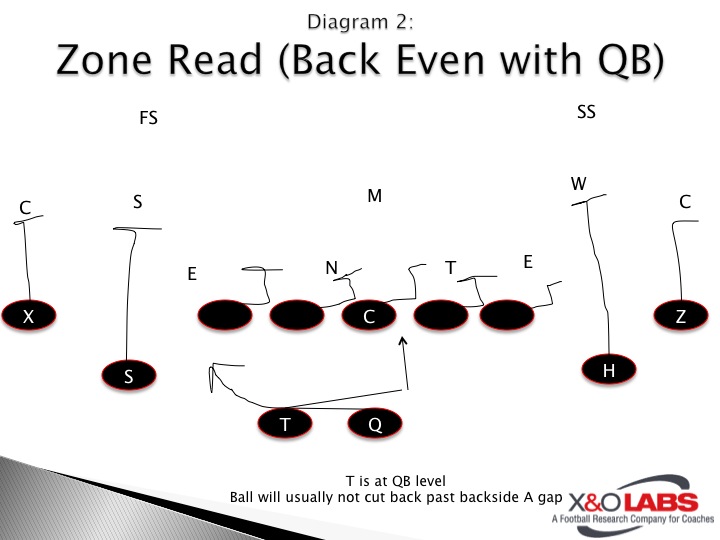

- Zone Read Teams: This means the back is aiming for the outside foot of the guard. Zone teams cross the center and go to the opposite guard. There is no real threat of a bend back. It’s an away side play. The QB is a threat to run it if you’re not honoring him. Most teams that run the pure zone read these days will have the back even with the QB because there is no real threat of a wind back – they are looking to puncture (diagram 2).

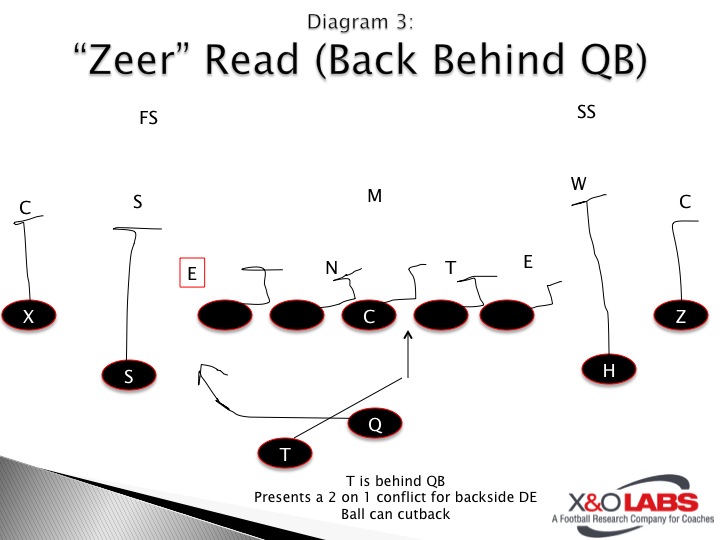

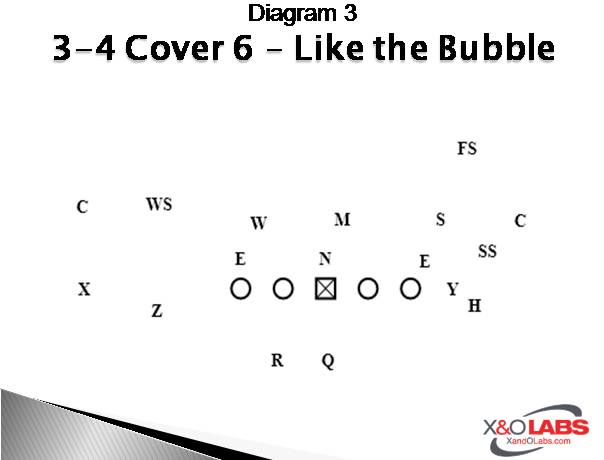

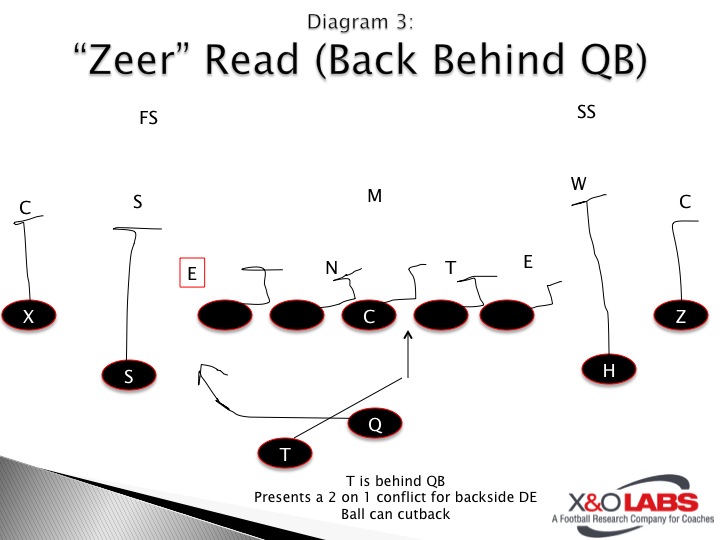

- “Zeer” Read Teams: This is a combination of veer/zone read schemes. These plays hit downhill like a veer. Now it’s a read because they try to put a two on one conflict on a DE. Many of these schemes are run out of the pistol or the broken pistol formation (diagram 3) that we’re seeing so much of now in the college game.

“There are two ways teams block it – they zone it or man it,” says Aranda. “Zoning it is better for offenses. People will zone the front the LB’s will run to gaps and it would be 4 on 3 and a crease for the back. Guys would just run to gaps back-side and the Zeer play would hit front side. You need to have 2 guys take two for one up front and have a LB to fall back.”

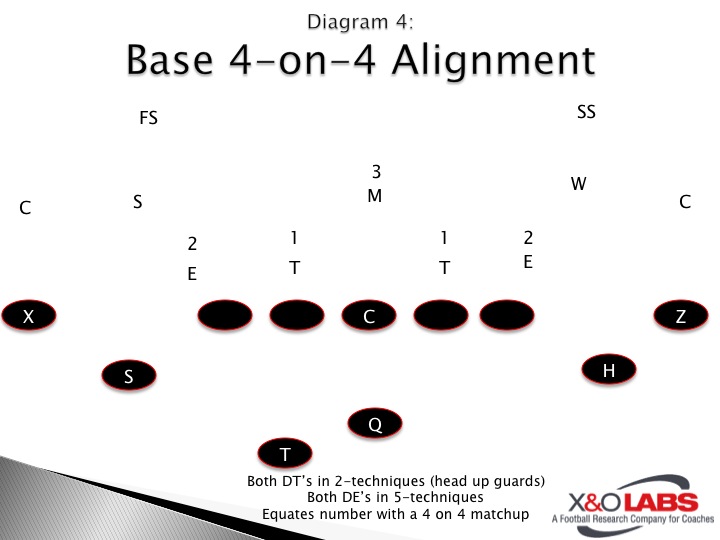

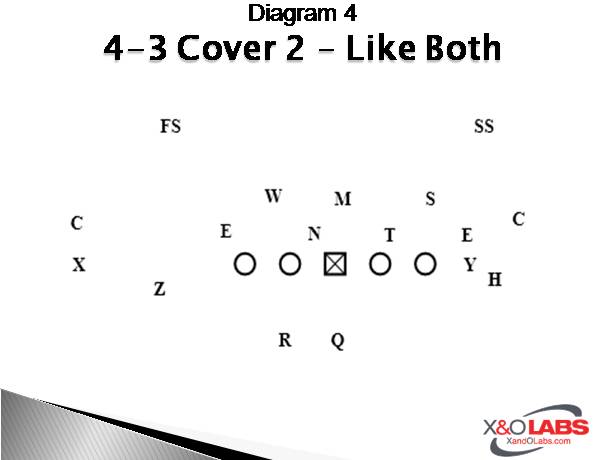

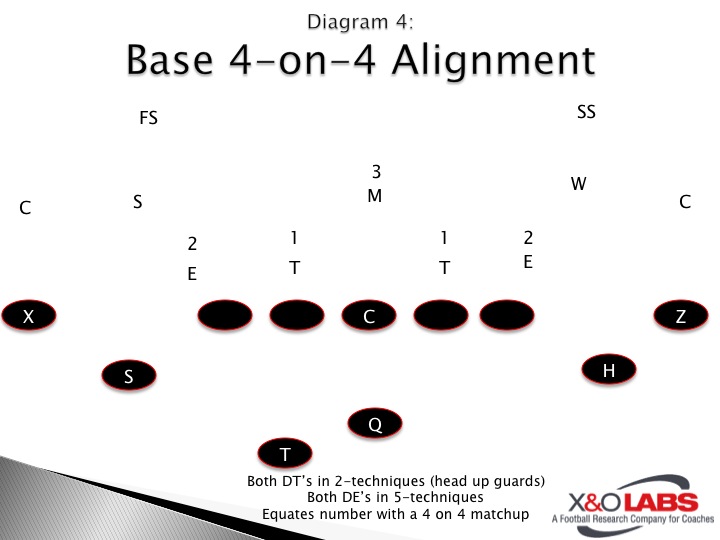

So when playing the Zeer read teams, Aranda plays with two 2-techniqes who “pre-snap” play B gap responsibility, two 5-techniques who play C gap inside out, with the Mike an A gap player inside out (diagram 4). But once the zone is declared the back-side 2-technique is the back-side A gap player. The Guard and Center wind up blocking one 2-techniue while the guard and tackle block the other 2-technique. Aranda talks about it being the same type of block, but how he coaches it is most important to learning the two-gap scheme. Since he feels the tackles are the most important component of the scheme, we’ll start there.

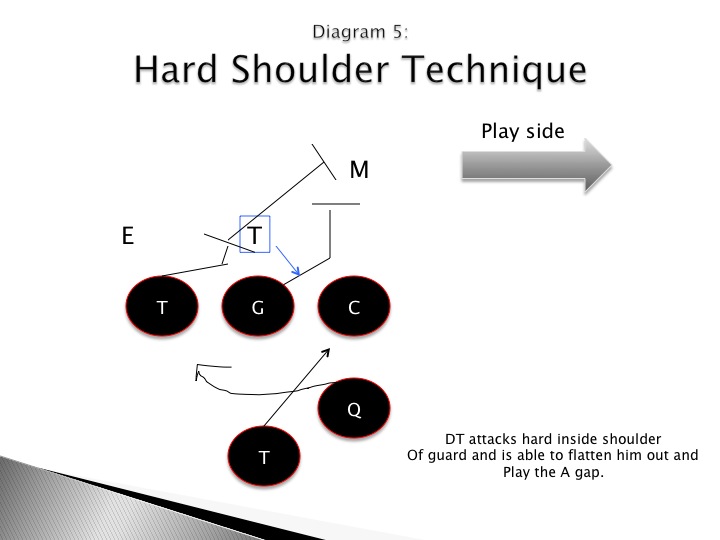

2-Technique: Using the Hard-Shoulder Technique

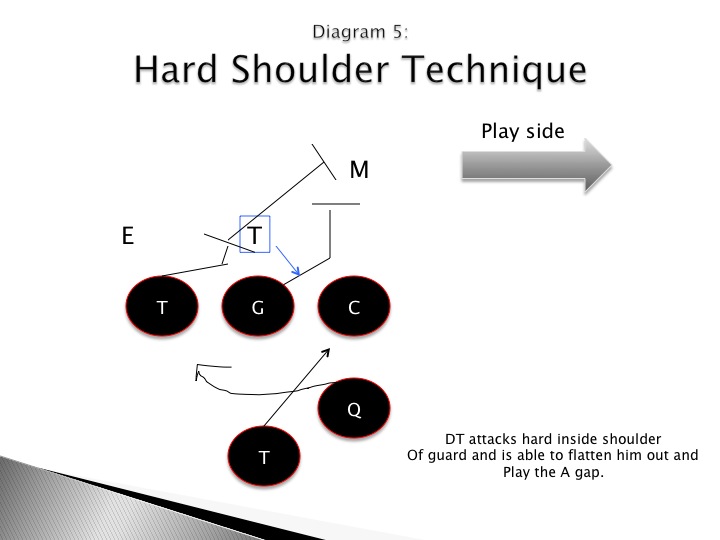

Aranda aligns his defensive tackles head up the offensive guard and he calls them his read attack player. His job is to play the back-side block of the guard. “We will either get a surge to the right or the left,” says Aranda. “The guard is trying to set him up one way and the tackle will try to knock him out one going inside or the center will knock him out going outside, depending on where the play is going. The tackle will try to knock him and try to work up to our Mike LB (diagram 5). He wants to go hips, hands and feet into blocker. We talk about lifting blockers; we want to block the blocker. Take him where he wants to go. As the guard sets up inside, I want to take him inside at a 45-degree angle. We talk about fighting the hard shoulder.”

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

By Mike Kuchar Senior Research Manager X&O Labs

Most of the spread coaches that we spoke with stress the value of patience. They want to be patient with their play calling, choosing to methodically march down the field blocks of yards at a time. They want their quarterback to be patient with his reads – quickly diagnosing coverage before peppering defensive secondary’s with intermediate throws. They even want their running back to be patient for gap displacement when running those zone read schemes synonymous with spread offenses.

But, often times patience can crumble – coming in the form of a speed rusher off the edge or a defensive tackle looping around for contain on zone pressures. While offensive coordinators teach patience, defensive coordinators demand quickness – sending as many rushers to the quarterback as possible without compromising coverage. Eventually, the offense needs to get plays off in a hurry – and in the face of the blitz. We’ve surveyed the coaching industry to provide you a report on how to be effective in the eye of the storm, when that zone pressure comes.

Case 1: Identifying Zone Pressures When covering the topic of zone pressures, there is one common denominator amongst all defensive coaches we speak with. They all tell us the first thing they teach is to “keep the shell” and disguise rotation. What this means, is that pre-snap the defensive secondary should always resemble some form of a two-safety defense. Eventually, one of those safeties will need to get to his landmark and coverage responsibility by the time the ball is snapped. The question is when. Good coordinators teach those safeties to disguise as much as possible – often dropping a split second before the ball is snapped.

Before we address what we discovered as some of the top defensive indicators to tip off a zone pressure, we went the extra mile for you, offensive coaches, in order to help you better disguise your snap count. If you’re a shotgun team, the most frequent indicators seem to be some sort of hand or leg movement – such as crossing or clapping your hands so the center can see it or lifting or moving a leg (similar to the classic John Elway move). If you’re more of an under center quaterback, we’ve found many teams will start their movement when your head comes back to the middle of the formation after looking right and left or the drop of your head immediately before the snap is delivered.

We’ve found that defenses have their “dead giveaways” as well before they start to rotate into their fire zone coverage. While the majority of offensive coaches will key one of the deep safeties to see who drops pre-snap (54.5 percent of our coaches say that’s the first thing they look for), we’ve found there are a few other indicators that hint at a zone pressure coming your way:

- The 3-technique DT is in the boundary: Almost all four down teams place their 3-technique to the field or offensive strength. If he lines up to the boundary and if he’s wide (because he becomes the contain player on pass) chances are a pressure is coming.

- The nose guard is in a shade alignment rather than a 2i on guard: Again, most four down teams play with a 2i and not a shade. If he’s in a shade alignment (outside shade of center) there is a good chance he will be crossing the center’s face to get into the opposite A gap.

- The five technique DE is to the field: Many zone pressure teams blitz from the field (there is more room there, obviously) and that defensive end needs to spike into the A gap. If he’s tight on that offensive tackle, you can bet he’s coming inside.

- The spin safety starts to creep: Like we mentioned earlier, he will eventually begin to spin down to take care of his pass responsibility if he’s dropping. If he’s coming, expect him to creep a lot sooner.

- The deep safety changes alignment: If the ball is on the hash and that inside safety is now inside the hash and over the center (as opposed to playing his deep half responsibility in most cases) he will be rotating to the middle of the field. QBs need to see that and expect some sort of three deep, three under pressures.

We were able to spend time visiting with Shawn Watson, the offensive coordinator at Nebraska, who really simplified his methodology in how he prepares to attack zone pressures. “Really, there will only be three types of pressures you will see,” says Watson. “You have external (outside) field pressures, external boundary pressures, and finally internal (inside) pressures. Once we identify those it’s easy to attack them. Even at our level, rarely is there a balanced pressure team that is effective at all three of those types. They believe in one thing or another – they won’t do all. I see a ton of field pressure teams for the most part – where they will overload the field and bring pressure.”

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

By Justin Webb

Co-Offensive Coordinator/Offensive Line Coach

Tioga High School (LA)

Unbalanced formations have been around the sport of football for hundreds of years. This concept has been and is being used throughout football in numerous styles of offenses. It all began with the Unbalanced Line Single Wing. Eventually, the Straight T and Wing T came along and were popular in the 60’s and 70’s. It was at that point, formations became balanced with two tight ends and even number of linemen on each side of the ball. From there, we saw the development of the Wishbone Option/Veer offenses from coaches all over the nation. The one concept that all of those offenses and schemes have in common was the utilization of the Unbalanced Line formation. Unbalanced formations have been around the sport of football for hundreds of years. This concept has been and is being used throughout football in numerous styles of offenses. It all began with the Unbalanced Line Single Wing. Eventually, the Straight T and Wing T came along and were popular in the 60’s and 70’s. It was at that point, formations became balanced with two tight ends and even number of linemen on each side of the ball. From there, we saw the development of the Wishbone Option/Veer offenses from coaches all over the nation. The one concept that all of those offenses and schemes have in common was the utilization of the Unbalanced Line formation.

The Unbalanced Line is identified by the use of an extra offensive lineman on either side of the ball. This could mean using a “Tackle Over Set” by placing a Offensive Tackle at the Tight End Position or even an extra Offensive Lineman on one side of the ball to create an “unbalance in numbers”. Teams all over the nation and at all levels (pro, college, high school) utilize this concept to create a numbers or strength advantage both in the running game and passing game. Some teams that I enjoy studying and watching employ this tactic are Wisconsin and Michigan State who both employed 5 Offensive Linemen on one side of the ball late in the 2012 season. Option teams such as Georgia Tech, Navy, and Army make use of this tactic pretty regularly as well. Even passing teams such as SMU and Missouri utilize an Offensive Lineman at the TE position to help with pass protection or provide some size and strength for the running game in a predominantly passing offense. There are numerous other teams that employ this strategy and most of those teams were covered in a previous article on X’s and O’s labs a few months back.

“What We Do”

The focus of this article is going to be a little different in its approach to this long-time formational strategy. I am going to show you how we use this strategy to our advantage at Tioga High School. We are an Unbalanced Direct Snap Single Wing offensive team and have been for 1 full season. Our overall philosophy is to outnumber you at the point of attack and create blocking angles to counteract the defense’s overall size and speed. Each and every week defenses must change the overall structure of their defense to defend us. That in of itself is a major advantage for us. This philosophy is a major reason option teams are who they are. We do not devote any time to perfecting the option game. We simply line up running the same Power Off Tackle plays that every run oriented team runs, however we run them out of an Unbalanced Line.

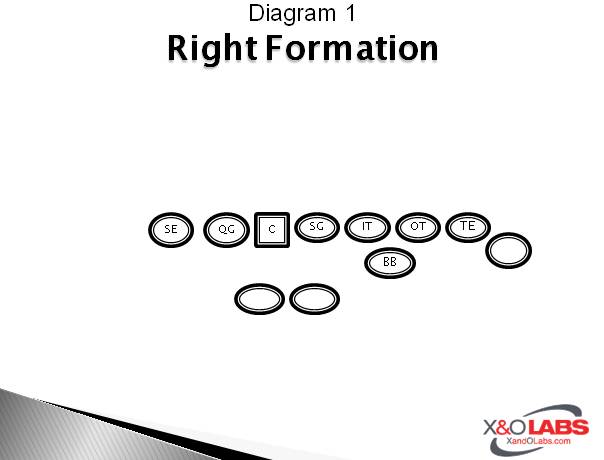

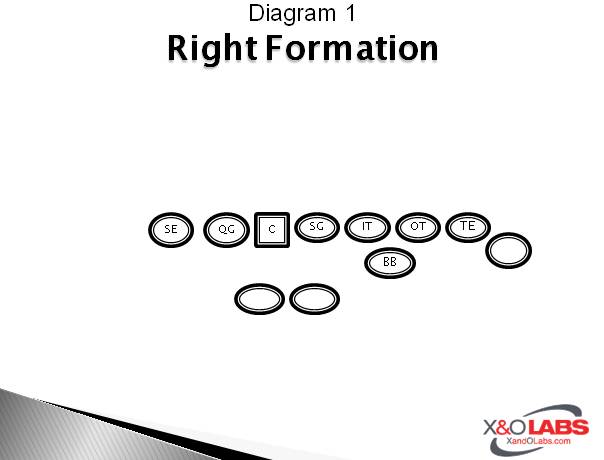

We operate out of our base set, which we call “Right” (See Diagram 1). Our positions are (starting from Right to Left) the Tight End, Outside Tackle, Inside Tackle, Strong Guard, Center, Quick Guard, and Split End. We operate out of this line structure about 85-90% of the time. We have ways of balancing up and getting into a Double TE set, but our bread and butter is the basic Unbalanced Line alignment. We can adjust our backfield and our formations to present a number of different looks in order to outflank and outman a defense at the point of attack. But, the constant variable is that we use an Unbalanced Line.

Technique

The secret to any scheme are the fundamentals up front. This is not a “magic pill” offense and/or philosophy. As a whole, we are no different than college teams such as Alabama, Wisconsin, or in many ways Auburn. The key to any offense is that you must be successful up front with the offensive line. These guys must be coached up on fundamentals, steps, and scheme. The most difficult aspect of adopting the overall philosophy of an Unbalanced Line is to make blocking rules and techniques match up to what you coach day in and day out. We are a 100% gap/down blocking scheme. Our feature play is the Power Off Tackle play. Our technique that we implement is Severe Angle Blocking (SAB). We execute 2 different types of techniques with our SAB technique (see diagrams 2 and 3 below).

>> X&O Labs Members: Login here to continue reading

Join X&O Labs to Continue Reading…

When you join X&O Labs, you’ll get instant access to the full-length version of this report — including access to everything in The LAB and Film Room. That’s over 4,000 reports and videos.

Read More

|

Editor’s note: Veteran Athletic Director and former head high school coach Chris Fore, conducted a lenghty research study on what makes successful football programs. Fore reached out to 108 head coaches from 42 different states nationwide and published the contents of his study in a book entitled Building Championsship-Caliber Programs which can be found here: http://eightlaces.org. Senior Research Manager Mike Kuchar interviewed Fore on some common denominators on successful progams.

Editor’s note: Veteran Athletic Director and former head high school coach Chris Fore, conducted a lenghty research study on what makes successful football programs. Fore reached out to 108 head coaches from 42 different states nationwide and published the contents of his study in a book entitled Building Championsship-Caliber Programs which can be found here: http://eightlaces.org. Senior Research Manager Mike Kuchar interviewed Fore on some common denominators on successful progams.

Editor’s Note: Coach Holzer has served as the Meade Mustangs Head Coach for two seasons from 2011-2012. He was named Coach of the Year by Varsity Sports Network for the State of Maryland as well as by The Capital Gazette, Baltimore TD Club, & Annapolis TD Club. From 2008-2010 Rich was Head Football Coach at Parkdale HS in Riverdale, MD. 2004-2008 Rich was Defensive Coordinator/ Strength Coach at Westlake HS in Waldorf, MD. 2002-2003 Rich was a GA at Hofstra University. Rich is graduate of Hofstra University with a BS in Physical Education, where he was also a 2x All League Offensive Lineman for the Pride, & has a Masters in Educational Administration from McDaniel College.

Editor’s Note: Coach Holzer has served as the Meade Mustangs Head Coach for two seasons from 2011-2012. He was named Coach of the Year by Varsity Sports Network for the State of Maryland as well as by The Capital Gazette, Baltimore TD Club, & Annapolis TD Club. From 2008-2010 Rich was Head Football Coach at Parkdale HS in Riverdale, MD. 2004-2008 Rich was Defensive Coordinator/ Strength Coach at Westlake HS in Waldorf, MD. 2002-2003 Rich was a GA at Hofstra University. Rich is graduate of Hofstra University with a BS in Physical Education, where he was also a 2x All League Offensive Lineman for the Pride, & has a Masters in Educational Administration from McDaniel College.

Editor’s Notes: Justin Iske begins his fourth season on the coaching staff at Fort Hays State in 2014. Iske coaches the FHSU offensive line and serves as the team’s strength coach. In Iske’s first three seasons at FHSU, he has coached seven All-MIAA selections on the offensive line, led by two-time second team selection Hawk Rouse in 2011 and 2012 and second-team selection Mario Abundez in 2013. The Tiger offensive line helped produce an average of over 2,000 rushing and 2,000 passing yards per year in Iske’s three seasons. Iske came to FHSU after two seasons at Northwestern Oklahoma State University where he was the offensive coordinator, special teams coordinator and offensive line coach. His 2010 team won the conference championship and led the conference in rushing offense, sacks allowed and kickoff returns.

Editor’s Notes: Justin Iske begins his fourth season on the coaching staff at Fort Hays State in 2014. Iske coaches the FHSU offensive line and serves as the team’s strength coach. In Iske’s first three seasons at FHSU, he has coached seven All-MIAA selections on the offensive line, led by two-time second team selection Hawk Rouse in 2011 and 2012 and second-team selection Mario Abundez in 2013. The Tiger offensive line helped produce an average of over 2,000 rushing and 2,000 passing yards per year in Iske’s three seasons. Iske came to FHSU after two seasons at Northwestern Oklahoma State University where he was the offensive coordinator, special teams coordinator and offensive line coach. His 2010 team won the conference championship and led the conference in rushing offense, sacks allowed and kickoff returns.

Editor’s Note: Scott grew up as a player for his father Steve Girolmo at Livonia High School in Western New York. A graduate of Cortland State (D-III – NY) he has coached at Castleton State College, and Western New England University as well as made stops in high school at his Alma-Mater Livonia and Liberty high School in Bealeton, VA. In 2012 he took over the offense at Liberty and has installed an ever-evolving hurry up no-huddle philosophy that mixes schemes from across the spectrum. As the Offensive Coordinator in their 2013 campaign the Eagles offense averaged 34.2 points per game, and was the 10th ranked offense in VHSL 4A. Scott is a diehard clinic enthusiast and encourages interactive Q & A regarding any of his contributions to the site.

Editor’s Note: Scott grew up as a player for his father Steve Girolmo at Livonia High School in Western New York. A graduate of Cortland State (D-III – NY) he has coached at Castleton State College, and Western New England University as well as made stops in high school at his Alma-Mater Livonia and Liberty high School in Bealeton, VA. In 2012 he took over the offense at Liberty and has installed an ever-evolving hurry up no-huddle philosophy that mixes schemes from across the spectrum. As the Offensive Coordinator in their 2013 campaign the Eagles offense averaged 34.2 points per game, and was the 10th ranked offense in VHSL 4A. Scott is a diehard clinic enthusiast and encourages interactive Q & A regarding any of his contributions to the site.

Editor’s Note: Rick Wimmer has been the head football coach at Fishers High School (IN) since 2006 when the school opened. Despite going 1-10 in the schools inaugural season while playing a varsity schedule with no seniors, the Tigers have recorded a 54-29 record in 7 seasons including 2 conference championships, 2 sectional championships, and the 2010 Indiana 5A State Championship. Prior to arriving at Fishers, Wimmer also served as head coach at Greenwood, Merrillville, and Zionsville High Schools. In 30 years as a head coach, Wimmer’s teams have compiled a 218-112 record earning 9 conference championships, 6 sectional championships, 3 regional championships, and 2 Indiana State Championships (2010, Fishers (5A); 1987, Zionsville (3A).

Editor’s Note: Rick Wimmer has been the head football coach at Fishers High School (IN) since 2006 when the school opened. Despite going 1-10 in the schools inaugural season while playing a varsity schedule with no seniors, the Tigers have recorded a 54-29 record in 7 seasons including 2 conference championships, 2 sectional championships, and the 2010 Indiana 5A State Championship. Prior to arriving at Fishers, Wimmer also served as head coach at Greenwood, Merrillville, and Zionsville High Schools. In 30 years as a head coach, Wimmer’s teams have compiled a 218-112 record earning 9 conference championships, 6 sectional championships, 3 regional championships, and 2 Indiana State Championships (2010, Fishers (5A); 1987, Zionsville (3A).

Ah…the battle tested Power O. It rivals the veer option as perhaps the most utilized offensive scheme in football. It’s tried and true – tracing back from the days when Woody Hayes fed the ball to Archie Griffin behind a stout fullback and those dominate offensive lines at Ohio State. “Four yards and a cloud of dust,” was not just a mantra but an offensive creed to live by. Even nowadays it’s rare to break down five minutes of game tape without seeing some remnants of the play show up at least a handful of times.

Ah…the battle tested Power O. It rivals the veer option as perhaps the most utilized offensive scheme in football. It’s tried and true – tracing back from the days when Woody Hayes fed the ball to Archie Griffin behind a stout fullback and those dominate offensive lines at Ohio State. “Four yards and a cloud of dust,” was not just a mantra but an offensive creed to live by. Even nowadays it’s rare to break down five minutes of game tape without seeing some remnants of the play show up at least a handful of times.

Editor’s Note: Coach Hayes have been a quarterbacks coach and a coordinator at the collegiate level for the past 8 years. Prior to being named as the offensive coordinator at Anna Maria, Coach Hayes was the quarterbacks coach at Copiah-Lincoln Community College and Assumption College. Brian has worked with a lot of great coaches from all levels and credits them with helping him develop as a young coach in this great profession.

Editor’s Note: Coach Hayes have been a quarterbacks coach and a coordinator at the collegiate level for the past 8 years. Prior to being named as the offensive coordinator at Anna Maria, Coach Hayes was the quarterbacks coach at Copiah-Lincoln Community College and Assumption College. Brian has worked with a lot of great coaches from all levels and credits them with helping him develop as a young coach in this great profession.

Great offenses are all about deception. Recently, there is a trend to package plays to allow for defenses to be wrong / confused regardless of the playcall. One of the most common ways that we have been able to do that within our offenses is to combine the age old buck sweep play from our Wing T roots with our 1 and 2 back shotgun formations. From there, we package plays in a way that the quarterback can make a simple pre-snap read to decide which of the plays in the package attacks what the defense is giving up.

Great offenses are all about deception. Recently, there is a trend to package plays to allow for defenses to be wrong / confused regardless of the playcall. One of the most common ways that we have been able to do that within our offenses is to combine the age old buck sweep play from our Wing T roots with our 1 and 2 back shotgun formations. From there, we package plays in a way that the quarterback can make a simple pre-snap read to decide which of the plays in the package attacks what the defense is giving up.

Grand Valley has always been able to score points. Dating back to its emergence on to the national stage under now Notre Dame Head Coach Brian Kelly, they have done much of this scoring by pushing the ball downfield in the passing game. I have personally set through multiple clinic talks by Kelly and his successor and now Notre Dame Offensive Coordinator Chuck Martin where they detailed both the importance of throwing it vertical and the schemes they use in that part of the game. I was always amazed at how they were able to be so consistent in creating big plays with these relatively simple schemes.

Grand Valley has always been able to score points. Dating back to its emergence on to the national stage under now Notre Dame Head Coach Brian Kelly, they have done much of this scoring by pushing the ball downfield in the passing game. I have personally set through multiple clinic talks by Kelly and his successor and now Notre Dame Offensive Coordinator Chuck Martin where they detailed both the importance of throwing it vertical and the schemes they use in that part of the game. I was always amazed at how they were able to be so consistent in creating big plays with these relatively simple schemes.

Unbalanced formations have been around the sport of football for hundreds of years. This concept has been and is being used throughout football in numerous styles of offenses. It all began with the Unbalanced Line Single Wing. Eventually, the Straight T and Wing T came along and were popular in the 60’s and 70’s. It was at that point, formations became balanced with two tight ends and even number of linemen on each side of the ball. From there, we saw the development of the Wishbone Option/Veer offenses from coaches all over the nation. The one concept that all of those offenses and schemes have in common was the utilization of the Unbalanced Line formation.

Unbalanced formations have been around the sport of football for hundreds of years. This concept has been and is being used throughout football in numerous styles of offenses. It all began with the Unbalanced Line Single Wing. Eventually, the Straight T and Wing T came along and were popular in the 60’s and 70’s. It was at that point, formations became balanced with two tight ends and even number of linemen on each side of the ball. From there, we saw the development of the Wishbone Option/Veer offenses from coaches all over the nation. The one concept that all of those offenses and schemes have in common was the utilization of the Unbalanced Line formation.