Defending Pre-Snap Movements: Statistical Analysis

The following Statistical Analysis Report is from the following Research Reports (click on the report name to access that specific report):

X&O Lab’ Mike Kuchar will meet with the staffs of 10 colleges in just 8 days this spring. Keep reading www.XandOLabs.com for all t

X&O Lab’ Mike Kuchar will meet with the staffs of 10 colleges in just 8 days this spring. Keep reading www.XandOLabs.com for all t

Offensive Line Coach

Utica College (NY)

Editor’s Note: The following clinic report was written by Utica College (NY) offensive line coach George Penree, a post he has held since 2007. In 2010 Utica broke more school-records including points in a single game (78), pass completions (231), passing a receiving yards (2,742), passing yards per game (274.2), total offensive yards (4,007), total yards of offense per game (400.7), and all purpose yards (5,049). Coach Penree will be happy to answer any comments or questions by leaving them below.

I would like to thank X&O Labs and all the great coaches who have influenced me over the years. I would like to discuss how we at Utica College teach the inside and outside zone using three-person groups, which is something we do once a week for a ten-minute individual period (five minutes for inside zone and five minutes for outside zone).

Before getting into the actual drills, a few things must be understood. The inside and outside zone blocking concepts are based on the teaching that in any inside or outside zone play there are “covered” and “uncovered” linemen.

I talk to my players about the different covered alignments a defender can have. The defender can either align to the play side (the side the ball is being run to), or backside (the side the ball is being run away from.) The covered lineman will first diagnose if he is covered play side, or covered backside. The uncovered linemen’s universal rule is to work with the next covered linemen to the play side. They have to diagnose what alignment the defender is in on the covered linemen they are working with. The covered lineman will make the call. If the uncovered lineman will look to the play side to identify the player and technique he is using. Once our guys understand these alignments, they then perform the technique best suited to block defenders in the different alignments.

I use these tables to organize all the techniques I have to teach in meetings and practice. It also gives our guys the ability to quickly recall the technique best used to block the defenders aligned across from them.

The table below explains the four situations we encounter on inside zone.

| Covered / Uncovered | Play side / Backside | Technique Used |

| Covered | Play side | Drive Block |

| Covered | Backside | Stab and Demeanor |

| Uncovered | Play side | Check and Climb |

| Uncovered | Backside | Lateral Drive |

The table below explains the four situations we encounter on outside zone.

| Covered / Uncovered | Playside / Backside | Technique Used |

| Covered | Play side | Reach |

| Covered | Backside | Reach, Stab, Climb |

| Uncovered | Play side | Reach, Check, Climb |

| Uncovered | Backside | Reach, Run, Takeover |

Blocking Technique Coaching Points:

Drive Block

Stab and Demeanor Block:

Check and Climb Block:

Lateral Drive Block:

Reach Block:

Reach, Stab and Climb Block:

Reach, Check and Climb Block:

Reach, Run and Takeover Block:

Determining Covered/Uncovered

By Mike Kuchar

Research Manager

X&O Labs

Two weeks ago, X&O Labs released its report on the Diamond formation run game. While we realized its balanced, three-back structure can produce a myriad of problems for defenses to defend the run, all of which we detailed in the prior report, we had no idea how many coaches were gashing coverages by putting the ball in the air. Although the Diamond formation may provide some generous one-on-one matchups on the perimeter (a key ingredient for the quick game) we’ve found that the majority of coaches will employ some play-action concepts in the formation.

Since the Diamond is still a relatively novel idea (although the T-formation old timers may tell you differently) the following report does not contain a ton of statistics and figures. It’s more of a collection of examples from coaches that reached out to us and wanted to pass their ideas along to you. It’s verbatim, straight from our surveys. As if that is not generous enough, they’ve even offered to answer any questions you may have. So when you’re done reading, feel free to ask questions or make comments below and these coaches will respond. By the same token, you’re always welcome to share what you’re doing at any time by contacting us (I can be reached at [email protected]).

We’ve broken down the Diamond formation play-action game into the following categories:

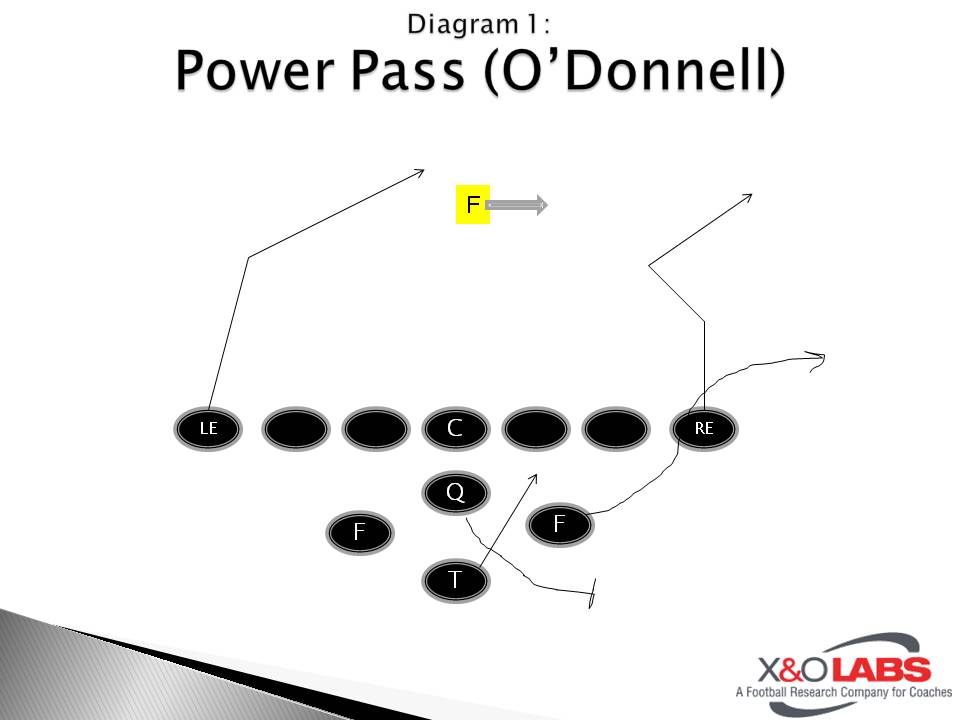

Play Concept (Power Pass)

Contributor: Mike O’Donnell, Rush City High School, Rush City (MN)

The most production pass action we have employed from the Diamond set has been to fake our power/lead play. We’ll look for the play side end who runs a post-corner route. At the same time, our near back who would be a kick out blocker on the defensive end in our lead play, would slide out into the flat after faking a block on the defensive end. This power/lead action tends to freeze the defense and keeps them committed to stopping the off-tackle action. By forcing the defense to check for the run first, we then get a two-on-one look with our play side end deep to the corner and our near back in the flat. At the same time, our backside end runs a post and looks for a deep opening in the middle of the football field. If the free safety moves out to help cover the post-corner route by the play side end, the post is wide open to the backside end. Diagram 1.

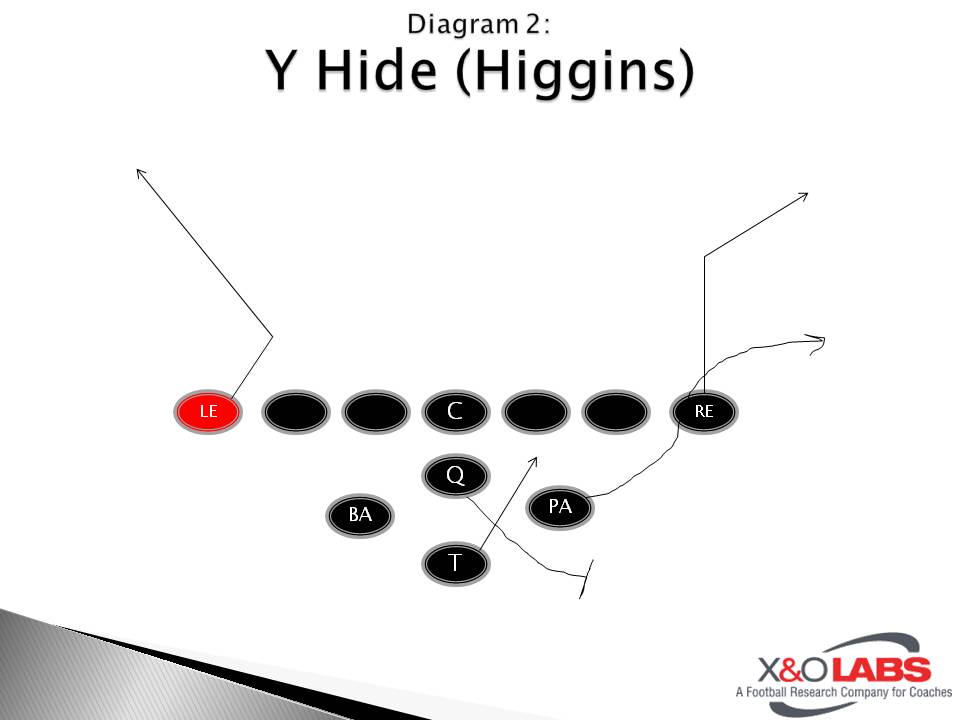

Play Concept (Y Hide)

Contributor: Dan Higgins, Cocoa Beach High School, Cocoa Beach (FL)

QB Check Downs: (diagram 2)

By Mike Kuchar

Senior Research Manager

X&O Labs

Researchers’ Note: You can access the raw data – in the form of graphs – from our research on the Diamond Formation: Click here to read the Statistical Analysis Report.

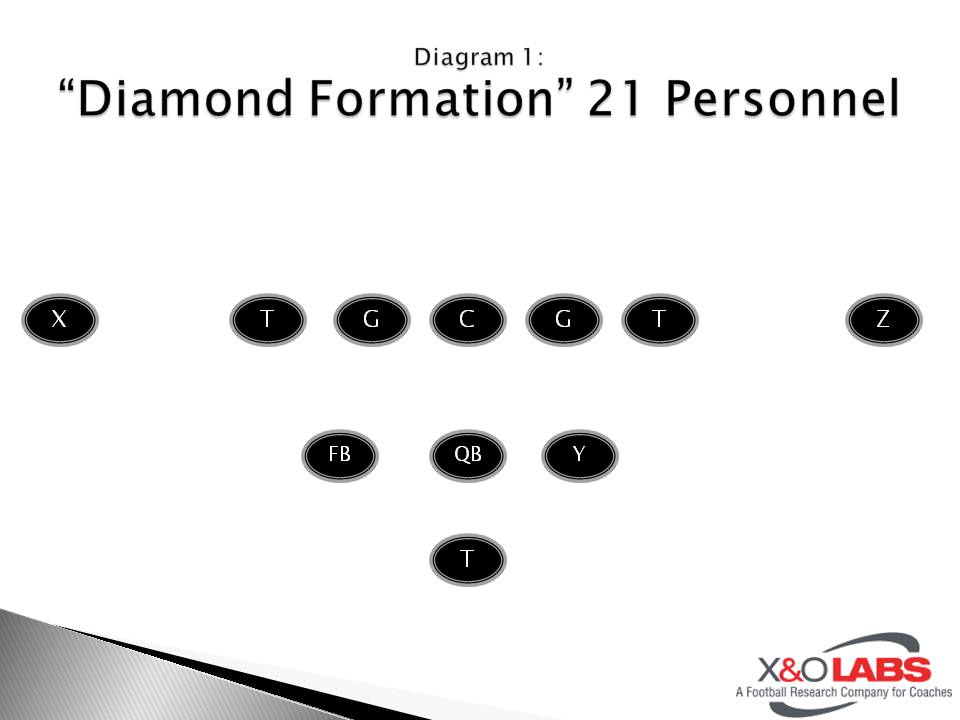

You’ve seen both the Pittsburgh Steelers and Green Bay Packers showcase it in front of millions of people in last year’s Super Bowl. Then you saw Bob Stoops at Oklahomatoy with it in Norman. Finally you saw former Oklahoma State offensive coordinator Dana Holgorsen bring it to a whole other level and dice defenses in Stillwater. It was “score at will” time for the Cowboys, propelling Holgorsen to his first head coaching job – now he’s doing it at West Virginia. So, chances are by now, you are familiar with at least the structure of the diamond formation (Diagram 1), but have you had the gaul to use it? If you’re like most of the coaches we spoke with, you’re still hesitating on dipping both feet in.

In fact, when we distributed our survey on the diamond formation to over 10,000 coaches we asked that only those that use the diamond formation respond…356 hit us back. Now we realize that it is clinic season, but that number should be a good indicator of how many coaches still have not incorporated the diamond formation into their offense. What’s more is that of those 356 coaches, 57.3 percent of them use it in less than 10 percent of their offensive schemes. Probably the most telling facet of our research was that of all of the coaches that use the formation said they will use more of it next season. If that’s not a testament to its value, we don’t know what is. But again, we’ll try to be unbiased in producing the following research – even if our coaches can’t.

When asked why they’ve decided to utilize the diamond formation, we got a laundry list of benefits. These are in no particular order.

Benefits of Using the Diamond Formation:

Case 1: Alignments and Personnel

We’ve found that when using the Diamond Formation, 49.4 percent of coaches will mainly run out of this set 75 percent of the time. While there are several opportunities to throw the ball, there is no question it is a run-first formation with lethal play-action possibilities off corresponding run actions. In the survey, we inquired about personnel and which is more suitable for running this formation. We’ve seen both: we’ve seen the Oklahoma State’s of the world run it out of 10 or spread personnel while professional teams like the Carolina Panthers used more 21 personnel with the addition of an H-Back. When our survey concluded, we noticed that 42.5 percent use 21 personnel while 37.3 percent use 10 personnel – these were the two personnel groupings of choice based on our coaches.

Tom McPherson, the head coach at Ridgeview High School (FL) uses both 30 and 10 personnel groupings in his diamond formation. When he’s in 30 personnel, he’ll have three viable backs (two sniffers and one tailback) to run his power and kick run game as well as his isolation run game. He’ll cheat his sniffers up to two yards from the line of scrimmage so they can get to the point of attack quicker. “We’re a no tight end team, so we have a hard time handling seven in the box,” said McPherson. “Now we can kick and wrap our sniffers and have seven blockers in the box. Our traditional diamond set is the only three back set where I use 10 personnel. I think in terms of bigger backs or smaller backs. Changing personnel helps with practice planning because I’m not going to do any jet sweep meshes with the big backs, only with the smaller skill kids in 10 personnel. I won’t ask a big back to be the jet sweep guy. He will only be the power guy.”

By Mike Kuchar

Senior Research Manager

X&O Labs

Last week, X&O Labs published part one of a two-part installment on the 17 biggest mistakes college assistant coaches make with their contracts. We’ve sifted through the fine print, and examined the details of hundreds of contracts. Although the process may have been tedious, the results were rewarding. To us, there is no better satisfaction than helping you, our readers, discover new coaching trends and information that help you better your program and career.

We’ve surveyed college level assistant football coaches and interviewed coaching agents, attorneys and employment experts – including lengthy research with the founder of a prominent coaches representation company, Dennis Cordell of Coaches, Inc. We’ve found what we consider to be The 17 Biggest Mistakes College Assistant Coaches Make with Their Contracts. These mistakes are in no particular order.

Before we advance, if you have not read part one of this two-part research report featuring mistakes and solutions #1 through #9 – please click here to read part one – you can come back here and read mistakes and solutions #10 through #17. Also, you can review the raw data – in the form of graphs – from our research of assistant coaches’ contracts: Click here for the Statistical Analysis Report.

The Problem:

This, of course, was only a problem when coaches weren’t pushing for it. NFL players often get bonuses for playoff appearances and personal productivityso why can’t coaches? Previously, what may have been a case of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” has now been brought to the forefront of negotiating.

The Solution:

The FCS (football championship subdivision, formerly D-1AA) teams have limited salary pools, but we’ve found establishing individual performance based bonuses beforehand are easier for Athletic Directors to sell to people across campus. “One of the problems in FCS is participating schools don’t generate playoff revenues as FBS schools do with bowl games.” says Cordell. “Although bowl bonuses are the norm in FBS, standard playoff bonuses for assistants are minimal to non-existent at the FCS level. If it was my client, I would ask for bonuses for common measurable achievements for his position group; such as rushing yards and RB all-conference honors for a RB Coach. You can also get creative, like having a bonus for losing less than three fumbles per year or averaging more than 5 yards per carry. This type of bonus money is easier for the school to swallow because it’s validated with numbers and does not apply to every assistant on staff.” Might as well ask, what do you have to lose?

By X&O Labs Research Staff

As coaches, we all see the prestige associated with coaching America’s greatest game. We flock to various conventions, scour over daily television reports and flood coaching websites hungry for the next job opportunity. So it’s not surprising when we see a former colleague, mentor or friend leave for greener pastures and land the next coordinator or position coach job. But what we don’t see is the handshake agreements that are not included in the contract, the neglected clauses and the other shortcuts taken to get a deal done in time for a press conference. The coaches themselves often don’t even realize their mistakes until they find themselves fired and left wondering where they went wrong. But by then it’s too late. In this X&O Labs’ Coaching Research Report, we are offering an exclusive look into the biggest and most common mistakes that are made in coaching contracts so that you don’t fall victim to them, too.

In 2011, researchers at X&O Labs have surveyed 1,800 college level assistant football coaches and interviewed coaching agents, attorneys and employment experts. We’ve found what we consider to be the 17 Mistakes College Assistant Coaches Make with Their Contracts. You can review the raw data – in the form of graphs – from our research of assistant coaches’ contracts: Click here for the Statistical Analysis Report.

You can’t change the brutality of the business of coaching college football, but there is one thing you can do – protect yourself and your family.

The following is part one of a two part report by X&O Labs. Part one features contract mistakes 1 through 9. In Part two, we will discuss contract mistakes 10 through 17 (click here to read part two). The following mistakes are in no subsequent order.

The Problem:

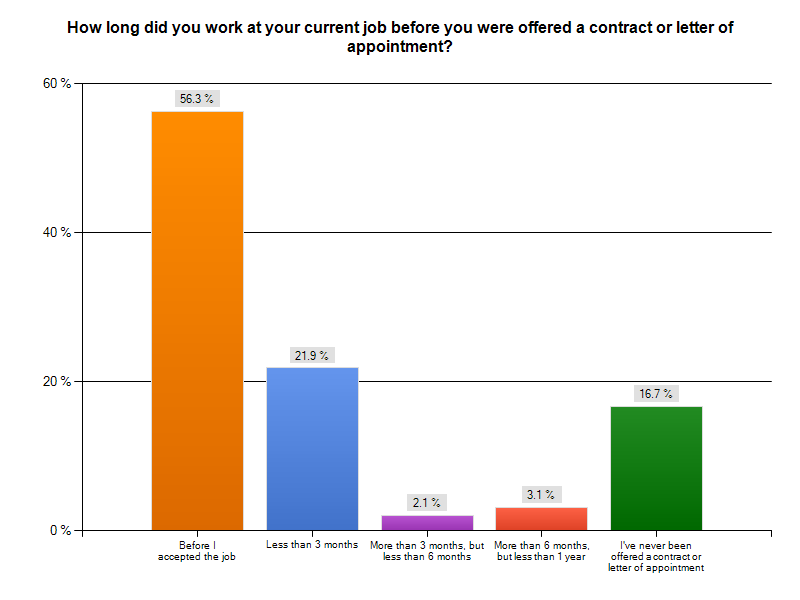

Perhaps the old coaching adage, “I’d do this for free,” does have some merit to it. Surprisingly enough, it’s not just the mid-major and small time programs that are buying into this philosophy. Over 36% of coaches polled have worked essentially on borrowed time by not having a contract. Even some NFL assistants we spoke with have not finalized their contracts. According to one BCS level coach, for the last two years he has worked without a contract from March to June and couldn’t get on the field for the first day of two-a-days in August because a contract had not been finalized.

This is one of the easiest traps to fall into. Many coaches are often hired right before spring football begins, so before they know it they’re caught up in drills and don’t have the time or legal assistance to finalize a written contract.

The Solution:

According to agent Dennis Cordell of Coaches, Inc., most teams want to form one-year contracts that offer no long-term job security. However, in recent years there have been more multi-year deals signed at FCS and FBS levels. “I think now you need to produce at least a two-year deal. If one of my clients needs to uproot his family and move across the country for a job, then he’s going to need more security. Not only do multi-year contracts protect the coach financially if he is fired before the contract expires, they also can deter schools from firing a coach when he has more than one year on his deal.”

The Problem:

We were surprised to see this one make our list. Keeping a copy of your employment contract on file is common sense. Shockingly, we found over 36% of college assistant football coaches do not have a copy of their contract signed by both parties.

As detail-oriented as coaches are when it comes to their programs, some are not meticulous enough to store away important documentation – documentation that can cost them tens of thousands of dollars.

During our research, one attorney who asked not to be identified shared an example of how important it is to keep a signed copy of your contract on file: “I sat in on conferences where there was a dispute with a $6 million signing bonus from a NFL defensive player. The franchise said they didn’t agree to a specific term – and the player lost out on all that money simply because he or his agent didn’t have a copy of his contract to prove it.”

Cordell added: “Some of the coaches I’ve signed still may not have a copy of their contract on them and need to check with their wives because they don’t know where it is. Often times they can’t produce it within 30 minutes.”

The Solution:

Keep a copy of your contract, signed by both parties, in a safe place that you can access within 30 minutes. In fact, one employment expert we talked with took this advice to the next level: “Every coach should keep the original signed copy of their contracts at home in a safe or fire box. I also have them scan the contract and keep on their computer in the event they need to email copies. And, obviously, your attorney or agent will always want a copy on file as well.”