By Jeff Smith

Special Assignment Researcher (X&O Labs)

Offensive Coordinator

Warrenton Central High School (MO)

Introduction

Utilizing the quarterback as a runner can be a detriment to any defense and it purely comes down to a simple numbers advantage. In the run game of conventional offenses, the quarterback is used to turn and hand the ball off taking him out of the numbers equation. It’s 10 (offensive players) vs. 11 (defensive players) football, meaning at least one defender will be unblocked to make the tackle. And that’s not including the potential of one getting off a block to make the stop. The quarterback run game forces defenses to account for him, often resorting to 8-9 man boxes with man coverage behind it (you will see plenty of those defensive structures in this report). And nobody does it better than Clemson as it pertains to designing formation and alerting their blocking schemes to make sure their top athlete (the quarterback) gets plenty of touches.

Once the defense starts to do load boxes and play man coverages, that’s when the big plays come in the pass game. We will detail those in case three. In case one we are going to focus specifically on the gap run menu for the quarterback.

What is a Gap Run?

Most offensive coordinators classify their run schemes into three genres: zone runs, gap runs, and man runs. This all depends on the blocking scheme up front. The crux of a gap-blocking scheme is double teams at the point of attack. These are two on one blocks where two offensive linemen are working against a down defender (such as a defensive lineman) and a second level defender such as linebacker. The benefit of doubles teams, aside from the numbers advantage, is that it creates instant movement on the line of scrimmage. This, in turn, creates opening up entry points for the ball carrier to run the ball. Modeled after the old Woody Hays power play at Ohio State, Clemson uses its gap runs out of open formations, with no attached tight end.

Why gap runs are effective in this system?

Clemson isn’t known for having the most stout offensive linemen up front, but they know how to move. The gap system cultivates this type of offensive lineman who are technically sound. As one of our researchers told us, “The offensive line doesn’t maul people, but they are sound. They stay on combo blocks until they absolutely have to come off." This is evidenced in our research below.

The second reason why Clemson is effective in its gap schemes is their use of open formations. Their use of four and five wide receivers sets spreads the defenses out. That formation advantage, coupled with double teams at the point of attack, usually equates to big gains in the quarterback gap run game. They also use open sets, shifts and motions more than most teams to spread the defense out and to make them think and adjust on the fly.

Gap Runs Used by Clemson:

QB Counter Concept

One of the more prominent gap runs in Clemson’s offensive menu is the QB counter concept. This is a scheme that they use with a variety of pre-snap shifts and motions. They also use a number of different read keys and the mix a sixth hat into their blocking scheme. Due to this scheme’s versatility, it allows Clemson to run it from multiple formations and personnel groupings. This keeps things simple and consistent for the offensive linemen, yet creates a lot of window dressing for defenses to worry about.

We start by looking at the Counter scheme for the offensive linemen. This scheme is exactly like a power blocking scheme, except instead of the puller climbing up to the 2nd level, they are looking to kick out the (EMLOS) end man on the line of scrimmage. To execute this type of scheme with success, there must have gap rules. Every team has specific terminology to accomplish this, which can be very complex. But in order to keep it simple these are the rules for front five.

Line Scheme and Front Rules

Play side Tackle and Guard

Center vs. Four Man Fronts

Backside Guard

Backside Tackle

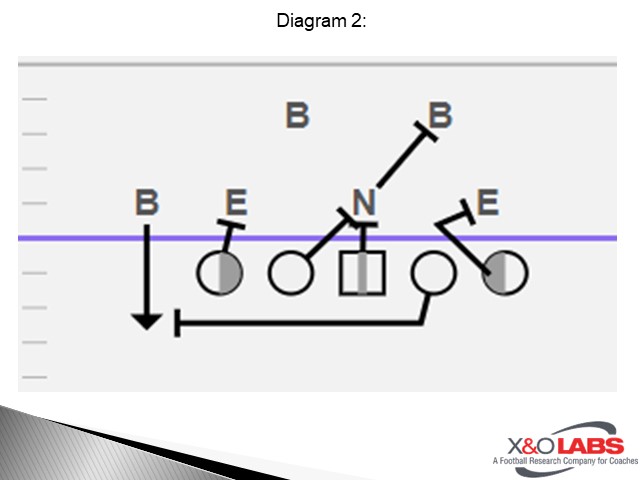

By working through these techniques, an offensive line is “building the wall” on the play side, which makes it hard for backside defenders to get through or over it. This combined with kicking out and logging the play side defenders. The diagrams below illustrate how to block the counter scheme against the two more common defensive fronts.

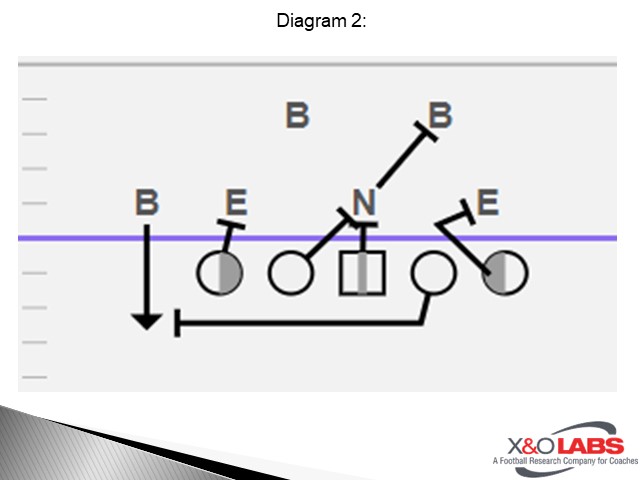

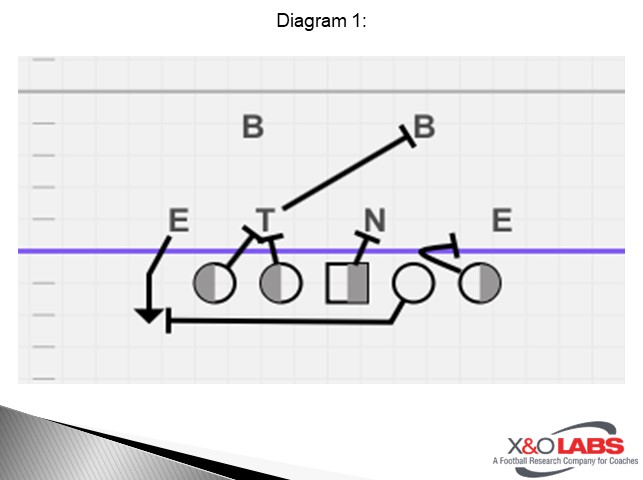

Counter vs 42 Over

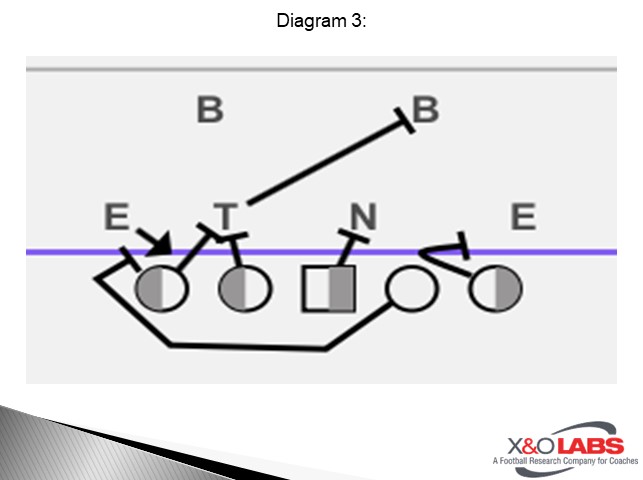

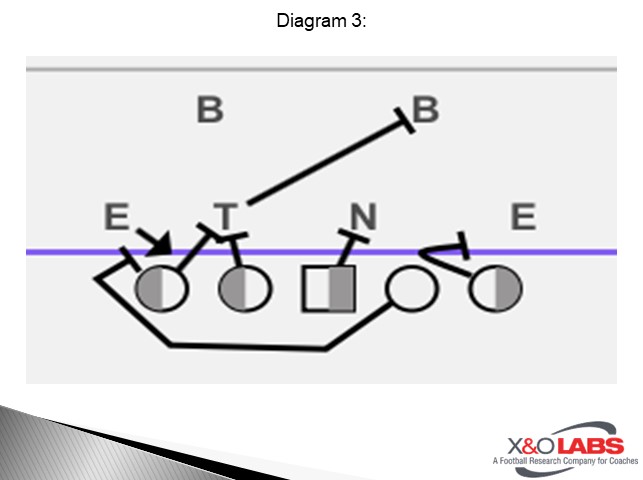

Counter vs 34

Blocking Variations

Those are the counter basics, but adjustments need to be made in order to run the play effectively against disciplined defenses and there are plenty of those in the ACC. So, in order to protect the base concept of the play, Clemson has to make alterations in its blocking scheme to take advantage of potential personnel mismatches.

Log Block

Again, the goal of this scheme is to kick out the EMOL and work inside of this block through B Gap. The quickest way to gash a defense is straight ahead. That being said, many defenses are taught to “spill” the ball, by making sure the defensive lineman that is getting kicked out, forces the ball outside on the perimeter where there are better athletes available to make a tackle on the quarterback. When this situation happens, the puller at Clemson is taught to read it and instead of trying to kick them out (which would be basically impossible) they will “log” them inside. This basically means they will work their head and hips to the outside of the EMOL and will look to seal them inside. This forces the play to bounce outside to C or D Gap. This means that the ball carrier needs to look to bounce instead of cutting back. See the illustration below:

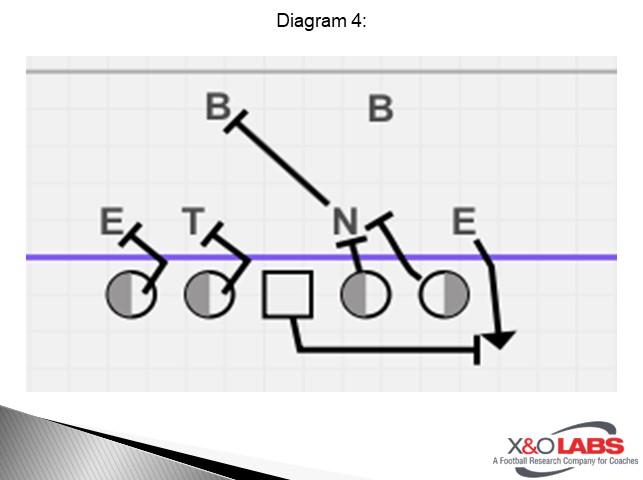

Counter vs 42 Over- Log Block

Center Pull

Four defensive linemen defenses, like the ones being used at the University of Miami at Virginia Tech in the ACC, usually possess a dynamic player at the 3-technique position. This block can be extremely difficult for a Center to execute a back block on. He may be too fast and get too much penetration into the backfield. In these circumstances, Clemson will pull its Center and keep its backside Guard on that dominant defender. The illustration below details this changeup.

Counter vs 42 Under- Wide 3 Tech, Center “Switch” Call

Insert Blocking

Special Assignment Researcher (X&O Labs)

Offensive Coordinator

Warrenton Central High School (MO)

Introduction

Utilizing the quarterback as a runner can be a detriment to any defense and it purely comes down to a simple numbers advantage. In the run game of conventional offenses, the quarterback is used to turn and hand the ball off taking him out of the numbers equation. It’s 10 (offensive players) vs. 11 (defensive players) football, meaning at least one defender will be unblocked to make the tackle. And that’s not including the potential of one getting off a block to make the stop. The quarterback run game forces defenses to account for him, often resorting to 8-9 man boxes with man coverage behind it (you will see plenty of those defensive structures in this report). And nobody does it better than Clemson as it pertains to designing formation and alerting their blocking schemes to make sure their top athlete (the quarterback) gets plenty of touches.

Once the defense starts to do load boxes and play man coverages, that’s when the big plays come in the pass game. We will detail those in case three. In case one we are going to focus specifically on the gap run menu for the quarterback.

What is a Gap Run?

Most offensive coordinators classify their run schemes into three genres: zone runs, gap runs, and man runs. This all depends on the blocking scheme up front. The crux of a gap-blocking scheme is double teams at the point of attack. These are two on one blocks where two offensive linemen are working against a down defender (such as a defensive lineman) and a second level defender such as linebacker. The benefit of doubles teams, aside from the numbers advantage, is that it creates instant movement on the line of scrimmage. This, in turn, creates opening up entry points for the ball carrier to run the ball. Modeled after the old Woody Hays power play at Ohio State, Clemson uses its gap runs out of open formations, with no attached tight end.

Why gap runs are effective in this system?

Clemson isn’t known for having the most stout offensive linemen up front, but they know how to move. The gap system cultivates this type of offensive lineman who are technically sound. As one of our researchers told us, “The offensive line doesn’t maul people, but they are sound. They stay on combo blocks until they absolutely have to come off." This is evidenced in our research below.

The second reason why Clemson is effective in its gap schemes is their use of open formations. Their use of four and five wide receivers sets spreads the defenses out. That formation advantage, coupled with double teams at the point of attack, usually equates to big gains in the quarterback gap run game. They also use open sets, shifts and motions more than most teams to spread the defense out and to make them think and adjust on the fly.

Gap Runs Used by Clemson:

- QB Counter Concept

- Counter Read Concept

- Power Read Concept

- Power Toss Concept

QB Counter Concept

One of the more prominent gap runs in Clemson’s offensive menu is the QB counter concept. This is a scheme that they use with a variety of pre-snap shifts and motions. They also use a number of different read keys and the mix a sixth hat into their blocking scheme. Due to this scheme’s versatility, it allows Clemson to run it from multiple formations and personnel groupings. This keeps things simple and consistent for the offensive linemen, yet creates a lot of window dressing for defenses to worry about.

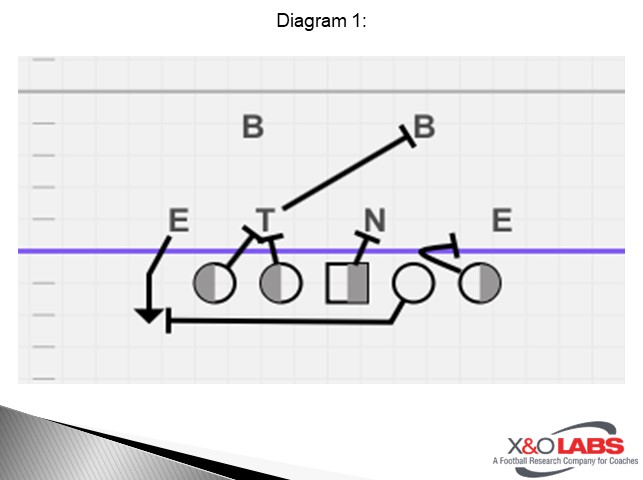

We start by looking at the Counter scheme for the offensive linemen. This scheme is exactly like a power blocking scheme, except instead of the puller climbing up to the 2nd level, they are looking to kick out the (EMLOS) end man on the line of scrimmage. To execute this type of scheme with success, there must have gap rules. Every team has specific terminology to accomplish this, which can be very complex. But in order to keep it simple these are the rules for front five.

Line Scheme and Front Rules

Play side Tackle and Guard

- Protect your backside gap.

- If it isn’t threatened, work a double team to the backside inside linebacker.

Center vs. Four Man Fronts

- Work down the line of scrimmage.

- If you can’t execute the down block because the defensive lineman is too wide, then make a “switch” alerting the pulling Guard that the Center will pull.

Backside Guard

- Flat pull and kick out EMOL

- If Center calls for a “switch”, protect A Gap and wheel back.

Backside Tackle

- Protect B Gap and wheel back.

By working through these techniques, an offensive line is “building the wall” on the play side, which makes it hard for backside defenders to get through or over it. This combined with kicking out and logging the play side defenders. The diagrams below illustrate how to block the counter scheme against the two more common defensive fronts.

Counter vs 42 Over

Counter vs 34

Blocking Variations

Those are the counter basics, but adjustments need to be made in order to run the play effectively against disciplined defenses and there are plenty of those in the ACC. So, in order to protect the base concept of the play, Clemson has to make alterations in its blocking scheme to take advantage of potential personnel mismatches.

Log Block

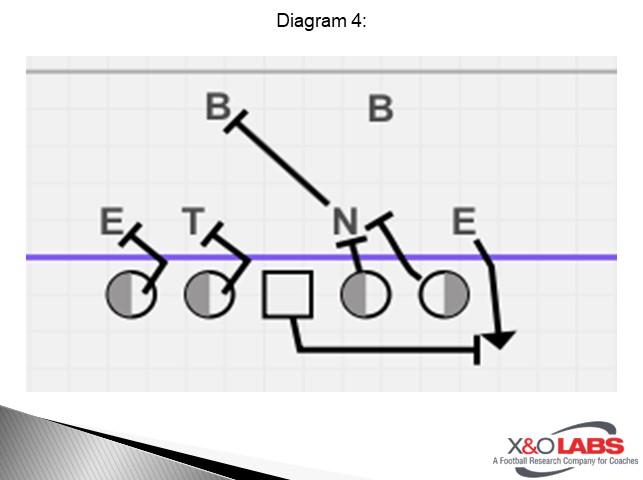

Again, the goal of this scheme is to kick out the EMOL and work inside of this block through B Gap. The quickest way to gash a defense is straight ahead. That being said, many defenses are taught to “spill” the ball, by making sure the defensive lineman that is getting kicked out, forces the ball outside on the perimeter where there are better athletes available to make a tackle on the quarterback. When this situation happens, the puller at Clemson is taught to read it and instead of trying to kick them out (which would be basically impossible) they will “log” them inside. This basically means they will work their head and hips to the outside of the EMOL and will look to seal them inside. This forces the play to bounce outside to C or D Gap. This means that the ball carrier needs to look to bounce instead of cutting back. See the illustration below:

Counter vs 42 Over- Log Block

Center Pull

Four defensive linemen defenses, like the ones being used at the University of Miami at Virginia Tech in the ACC, usually possess a dynamic player at the 3-technique position. This block can be extremely difficult for a Center to execute a back block on. He may be too fast and get too much penetration into the backfield. In these circumstances, Clemson will pull its Center and keep its backside Guard on that dominant defender. The illustration below details this changeup.

Counter vs 42 Under- Wide 3 Tech, Center “Switch” Call

Insert Blocking