By Mike Kuchar Senior Research Manager X&O Labs [email protected]

Researchers' Note: You can access the raw data - in the form of graphs - from our research on the sprint out pass game: Click here to read the Statistical Analysis Report.

Before we ruffle any feathers of the football purists in the world, it’s important to note that the following information may not be conducive to what you do offensively. Quite frankly, it pales in popularity to the zone read, bubble screen or power O. In fact, it may rate somewhere above the single wing scheme and the veer option. But, at X&O Labs, we felt the sprint out pass game was a topic worth studying. And why wouldn’t it be? Most programs now have an athletic QB behind center, so why not vary his launch point and give him the run/pass option to make plays in space? And if you don’t have an athletic signal caller, you can still be productive with the scheme, and we’ll show you how.

Whatever your situation, we recommend you read this entire report. You may find you can apply elements of our research to what you’re doing.

While it may be true that the majority of our readers – 63.3 percent – use the sprint out concept 25 percent or less of their offensive snaps – it does serve some merit in regards to when you dial it up. It’s a change-up call more than anything else. We’ve found through our research that unless you’re an option outfit, you won’t call the play with some degree of frequency. After all, who wants to put their QB through the stress of having to throw on the run on a consistent manner? It’s hard enough to do that alone, not withstanding six or seven defenders hunting you down from your blind side. Yet throughout time, it’s been a consistent third and short favorite particularly when you want to give your QB a chance to push the ball to the perimeter and make something happen in a hurry. Programs like BYU, Arizona State, Utah and Boise State – whom we have researched below – all have made a steady living off the play, particularly in those situations. It often puts the flat player in a bind – unable to make a decision of whether to tackle the QB or cover his pass responsibility, and before you know it, it’s a first down. Surprisingly, we had some resistance from coaches when we started to put this report together, so instead of giving you supporting evidence to run the sprint out scheme – we felt it was necessary to dispel the four main arguments or myths as to why some coaches are afraid of running the scheme.

Myth 1: Only Coaches With a Mobile, Athletic QB Can Run the Sprint Out Concept

Fact: According to our research, 64.1 percent of offensive coordinators still run the sprint out concept with what they would call an "immobile QB." So, it may depend on how well you can coach it.

Myth 2: It Cuts the Field in Half and Makes it Easier for Defenses to Defend

Fact: While this myth does make sense on the surface, we’ve found that cutting up the field can clean up the read of your QB, and we’ll show you how you can do it. Often times, it’s a one-defender read and by the time he makes a decision, you’ve either blown by him or dumped it off. It’s like defending a two-on-one fast break.

Myth 3: My Route Selection is Limited. I Got a Curl/Flat Combo and a Flood Principle. That’s it.

Fact: As Adrian Balboa so assertively declared in Rocky 3 "that’s not it!" Not only do you have your horizontal stretch combo’s, you can implement some vertical stretches as well – double moves are lethal in the sprint pass game. Remember, it worked for Balboa – he beat Clumber Lang.

Myth 4: Sprint Out is Only Effective in Shotgun Sets, and We’re Not a Shotgun Team

Fact: According to our survey, while it may be true that 70.4 percent of coaches prefer to run the scheme detached from the center, we’ve found that many of these teams still incorporate the route concepts under center as well. It’s all in the punch step or separation from the center, which we will explain later in this report.

Case 1: Pass Protection Dilemma: Turn-Back or Full Zone?

Case 1: Pass Protection Dilemma: Turn-Back or Full Zone?

I have to admit, I was anxiously anticipating the outcome of this facet of the survey. Through the years, I’ve heard so many arguments for either the turn-back or full zone protection. Proponents of the full zone protection talk about its simplicity of structure, allowing the QB to get to the edge quicker and either deliver the ball or pocket it. Yet, advocates of the turn-back scheme always talk about protecting the back-side of the QB first, and the best way to do that is to hinge back-side. This would lead you to believe that most teams will full zone the front side and turn back the back-side. What we’ve found is 61.2 percent of coaches execute a full reach front side with a turn back away from the center.

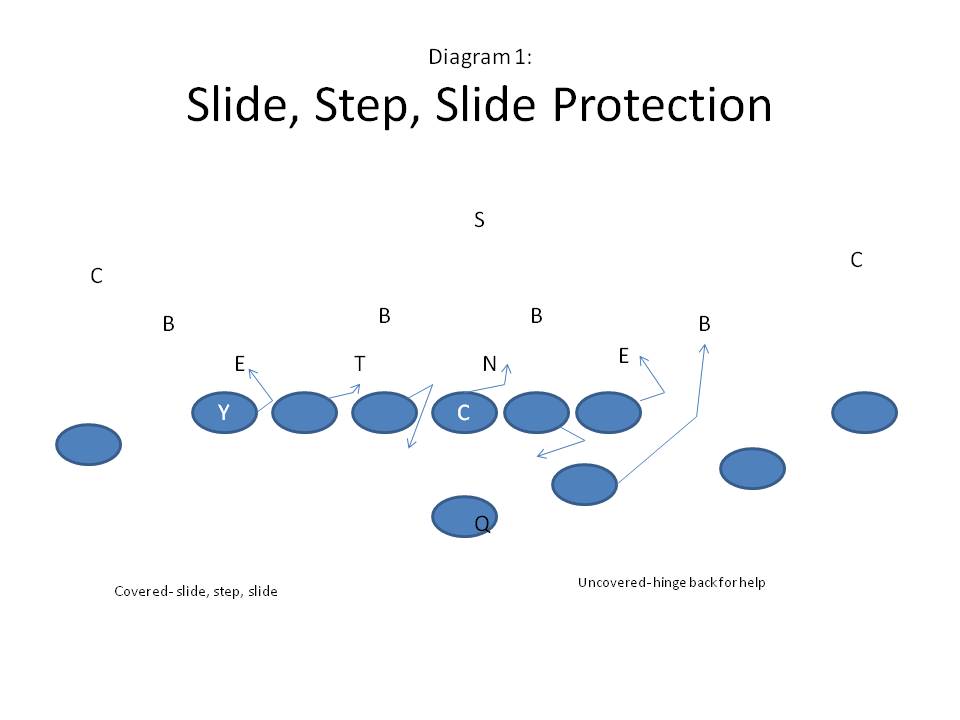

When we surveyed those coaches that incorporate the full zone principle in protection, 39.1 percent of them worked a full-reach step to get to the outside armpit of the defender, while 33.5 percent taught a bucket step. Doug Taracuk, the offensive coordinator at Dublin Scioto High School in Dublin (OH) combines both with the "slide, step, slide" action to his offensive lineman when working his protection schemes. He enforces the "nose to nose" rule, meaning that each player is responsible for the defender – either first or second level – that is from my nose to the next adjacent lineman’s nose play side.

"If you’re covered, you execute the ‘slide, step, slide’ technique. If no one is there, I hinge and help back side," says Taracuk (Diagram 1). "From our stance we step with the outside foot laterally for four to six inches. Some players may opt to bucket step depending upon the angle of intersection with the pass rusher. Our second step is a slide step back to our base athletic stance width. On this movement we want to end up with the outside foot. Our goal is to have the outside foot slightly outside of the defender’s outside with the inside foot splitting the crotch of the defender."

In order to reinforce the "slide, step, slide" action, Taracuk executes a dowel rod drill that he got from former NFL offensive lineman Doug Smith. A defensive lineman holds the dowel rod, about five feet in length with the width of a baseball bat, while an offensive lineman comes out of the stance with an inside hand position. The offensive lineman must hook the defender while keeping hand position on the dowel rod. According to Taracuk, it’s a terrific drill for quickness.