“The challenge lies in finding a defender with equal ability to match the skill set of the QB. More often than not you’ll need two skill defenders to handle that responsibility.”

- Bud Foster, former Defensive Coordinator, Virginia Tech University

By Mike Kuchar

Senior Research Manager/Co-Founder

X&O Labs

@MikeKKuchar

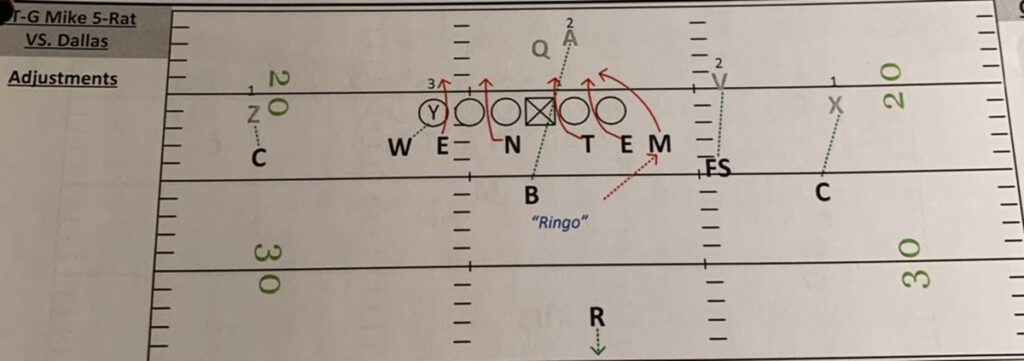

The Ideology: Getting a Plus One Rush

The premise is simple. Find the back in protection and overload him. It’s a philosophy that defensive coaches work tirelessly to achieve when designing their pressures. Truth is, Bud Foster was already building in these add-on rushes from a man cover perspective for years. During my visit, I was extremely impressed with the sophistication of his add-on rush system and how it was communicated by the front seven. This system consists of man pressures from the Mike, Backer, Rover, and Whip/Nickel position. They can be run as single huddle calls or built-in adjustments based on formation. All blitzes are communicated with a “Ringo” call meaning it’s coming from the right or a “Lucky” call meaning it’s coming from the left. Most are complemented with 5-Rat coverage, which is pure man free coverage although they can be used with Mini and Lock coverage as well. I’ve noticed he tends to call these on the first call of the game to generate some pressure on openers.

The rules of this system are below:

Defensive End to Blitz:

- Pinch Technique- step to Tackles crotch and cross over

Defensive Tackle to Blitz:

- 3-Technique= Tag (take the A gap)

- 2-Technique- Play normal

- Secure the opposite A gap, key the Center

Defensive Tackle Away from Blitz:

- 3-Technique- Play Normal

- 2-Technique= Spark into the opposite B gap

Defensive End Away From Blitz:

- Normal

The base man pressure calls in the system are as follows: Mike, Backer, Tango, and Rover.

These pressures are five-man pressures and can be run with the following base coverages:

- 5 Rat (man-free)

- Mini coverage

- Key coverage

- Quarters

It’s important to note that in man-free coverage these blitzers are in “shoot support,” meaning they will be asked to hammer the ball back inside to one another. All other defenders are in man coverage.

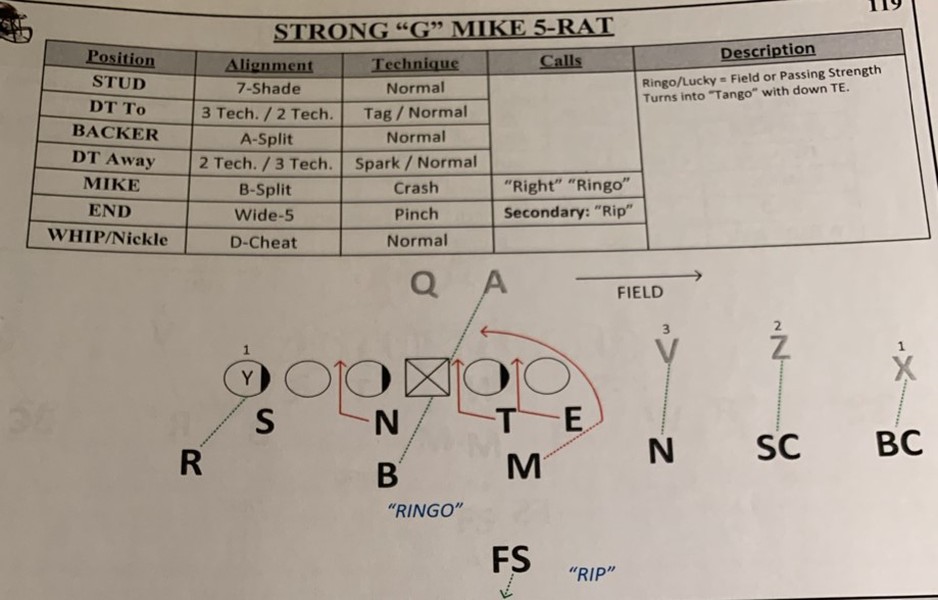

Mike Pressure:

Here is what the Mike pressure looks like vs. 2x2 formations:

Here is what the Mike pressure looks like vs. 3x1:

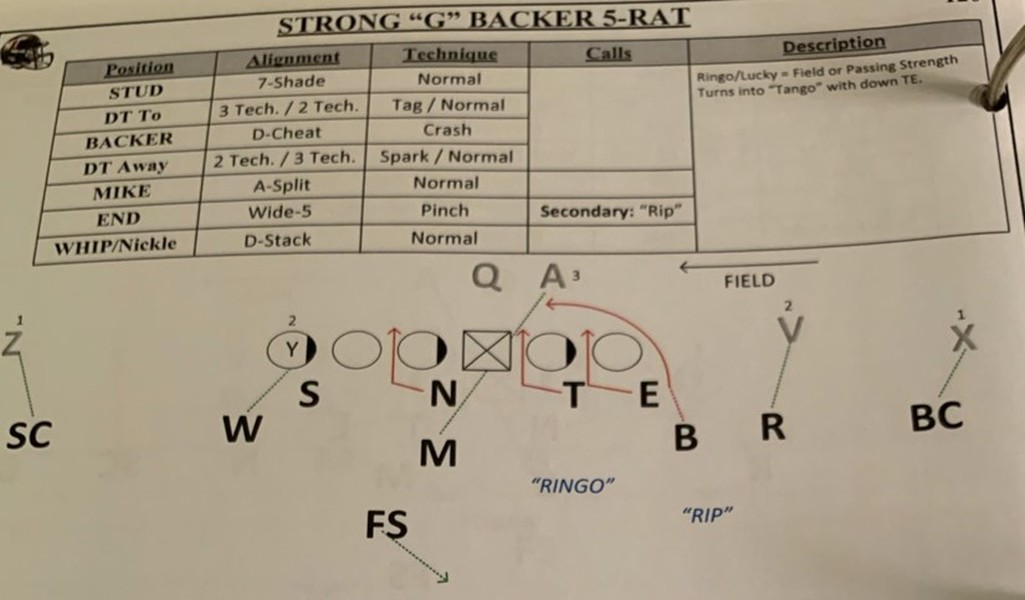

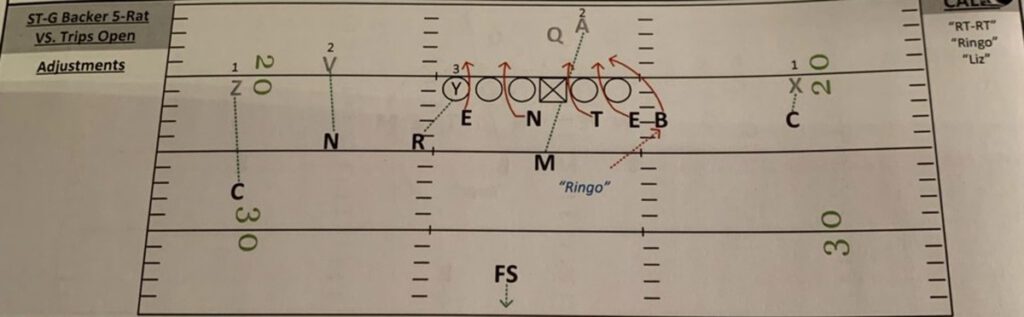

Backer Pressure:

Here is what the Backer pressure looks like vs. 2x2:

Here is what Backer pressure looks like vs. 3x1:

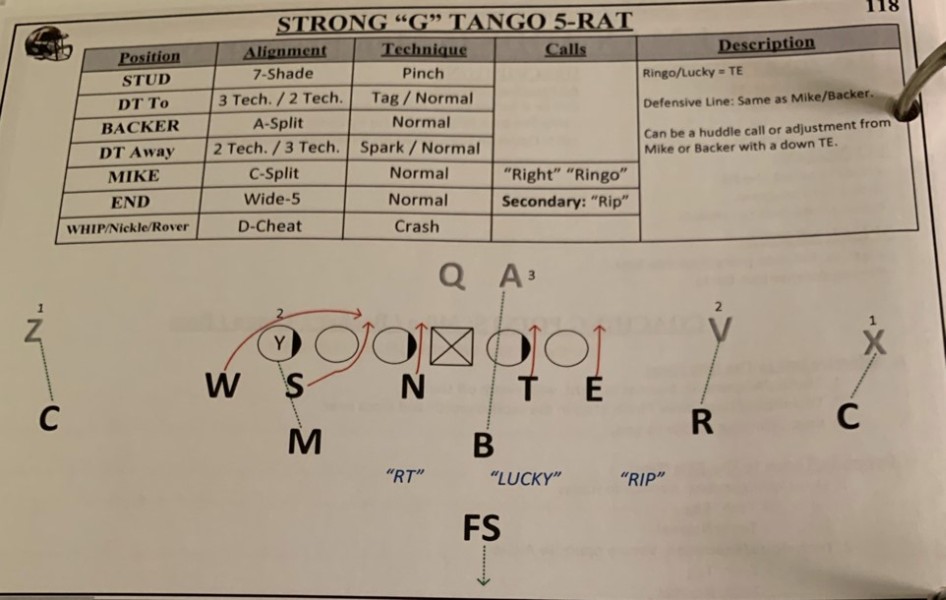

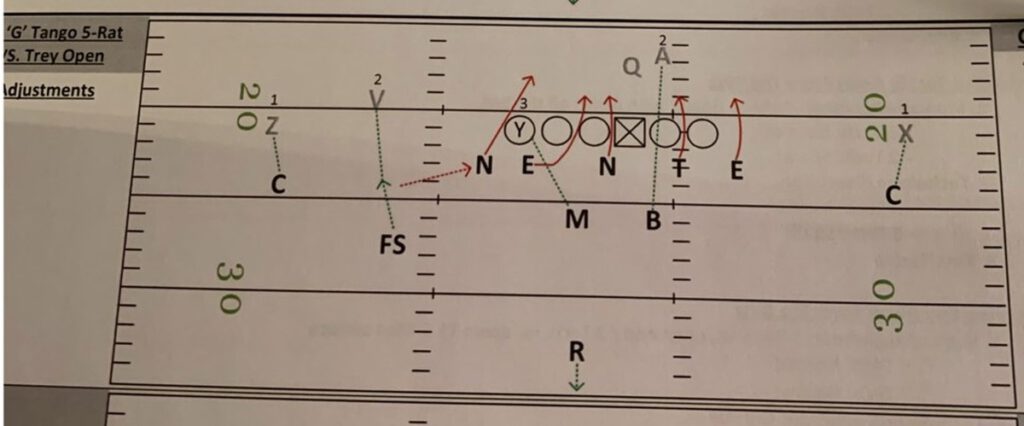

“Tango” (Whip/Nickel) Pressure:

Tango was predominantly a Nickel/Whip pressure off the tight end surface. It would be used against offenses that had a strong tendency as a tight end run team because it brought pressure right off the edge.

Here is what Tango pressure looks like vs. 2x2 formations to the field:

Here is what Tango pressure looks like vs. 3x1 formations to the field:

But now, here’s where his man pressure system progresses. Tango can often be used as a pressure check for any defender to pressure off a down tight end. Consider the scenarios below

- If the tight end is to the field (as in the diagrams above) the Nickel/Whip could blitz a down tight end.

- If it’s 2x2 with the tight end to the boundary, the Rover could be the blitzer.

- If it’s a Nub formation with the tight end into the boundary, the boundary corner could be the blitzer.

- If the tight end was off the ball in a sniffer alignment, the Mike or Backer could be the blitzer.

Essentially, whatever defender responsible for the tight end would be the pressure defender and the Mike or Backer would cover the tight end man to man. If the tight end stayed in to block, they would be scrape blitzers off his edge which is described below. Bud’s thought process was to just let cover players cover and be more gap controlled in the run game. The scrape pressures element to the blitz.

So much of his man pressure system is allowing the defenders the freedom to be in advantageous pressure alignments based on formation surface. Blitzer abided by unwritten rules like if the pressure is coming from a two-surface formation, the blitzer can be crash blitzer from depth and will automatically be the run support defender.

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point:

But if the blitzer is aligned to a three-surface formation, he is mandated to walk up and blitz from the edge to ensure that he cannot get sealed in the run game. “We don’t need to show it right away,” said Coach Foster. “But we can’t be in a position to get pinned.”

The clip below best illustrations this coaching point:

It’s important to note that he treats H/Y off formations like three-surface formations so the Mike would walk up and pressure the edge, leaving the Whip to play the Tight End. The safeties can now “chain” off the Y (because it’s a man coverage concept) or the safety to the side of the tight end can track him. Meaning, if the tight end blocks, the safety can add to the fit and be a bonus defender.

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point:

Since these are man pressure concepts, linebackers are told to gap fit and first-level defenders don’t wipe as they would in his zone pressure package (which is presented in the next ideology). Instead, the box linebacker not pressuring has an A gap to the ball responsibility.

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point.

One of the main coaching points for that A gap to ball player is to slow down and expect the ball to come back to him. In the Mike pressure clip below, the Backer is too fast over the top and the ball cuts back behind him.

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point.

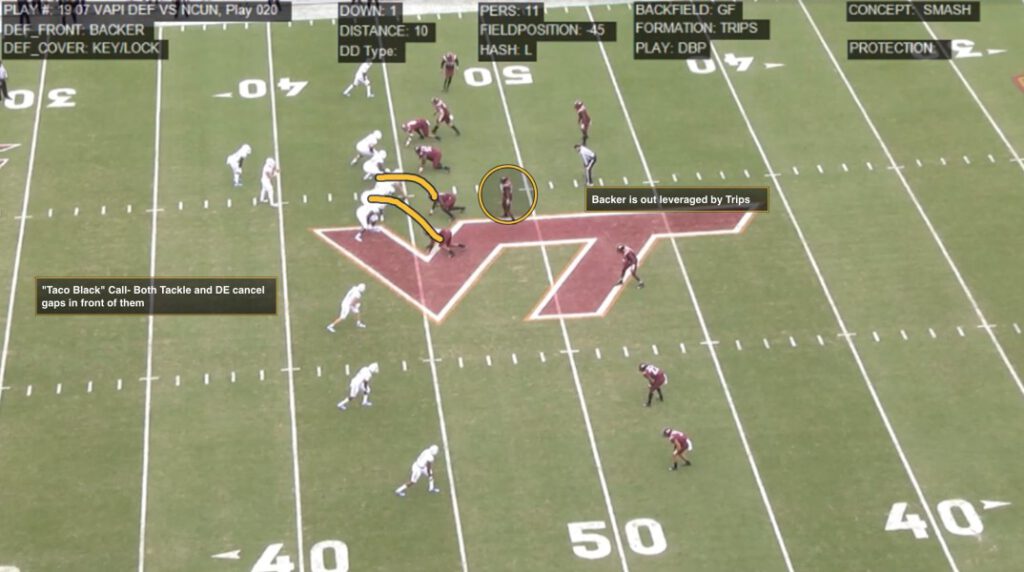

One of the things that should help the box backer vs. gap schemes is having the “Tagger” or defensive tackle to the side of the pressure cross face of the Center on any backblocks. This automatically cancels the play side A gap and allows the linebacker to flow to the ball. Those same run game responsibilities cannot be overlooked in this add-on pressure system. Crash blitzers must know that they are force defenders with run action to them. The opposite linebacker (Mike or Backer) must also understand that they immediately become the force defender opposite the blitz, which he calls this “shoot support.” They must be A gap to ball players. Again, if at any time they felt out-leveraged pre-snap they always were given the freedom to make “Black” calls alerting first-level defenders to cancel gaps in front of them. It would help get the ball pushed out in the run game.

I’ve noticed there have been several instances where these defenders lose leverage on the perimeter giving up a big run because defensive backs are in man coverage.

The clip below against North Carolina is an example of this:

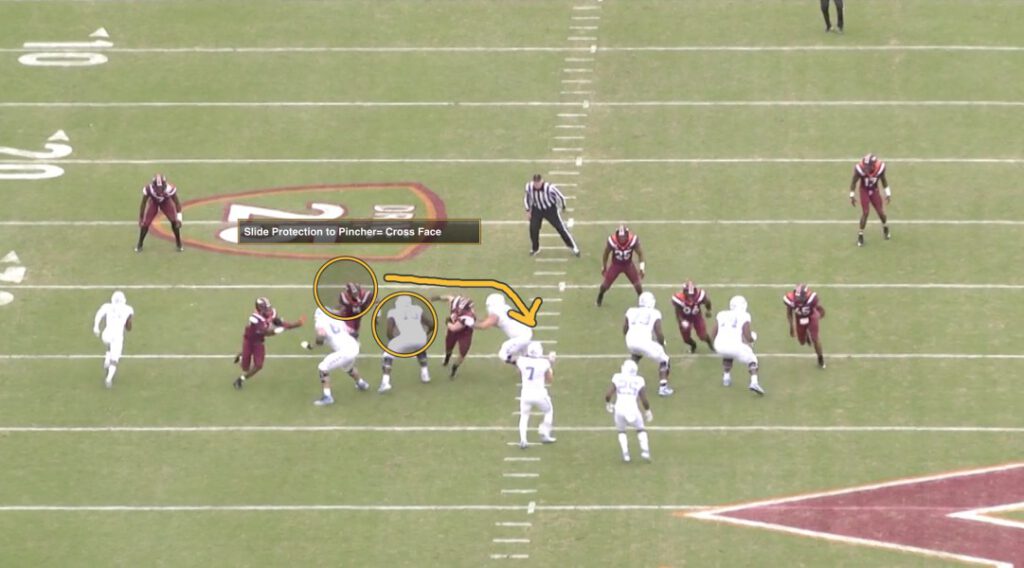

In the passing game, these pressures get translated into two on one matchup on the back when the tight end blocks. Against pure slide protect teams, I’ve found that he will continually make “Tango” calls, which tells the defender to the side of the tight end to blitz. And if the tight end blocks, the Mike or Backer to his side becomes another scrape rusher. This is where you get two on one with the back.

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point:

One of his built-in adaptations vs. slide protection was for first level defenders to the side of the pressure to cross the face of linemen that were setting the slide to them. As shown in the image below, this can alter the protection schemes and promote the possibility of a free rusher.

BTB (Blitz the Back) Pressures:

All of these man pressure concepts were then built around what Bud called his “Blitz the Back” or “Blitz” package. Now the defender (either the Mike or Backer) that was aligned to the back would execute the blitz, which can essentially become a “Mike” or “Backer” pressure. The same-add on principles applied if any offensive player blocked. So, if the back starts in one location and switches to the next, the call gets redeclared from a “Ringo” to a “Lucky” call. The blitzer can either walk up and come from the line of scrimmage (against a three-surface formation) or he can scrape and come from depth (against a two-surface formation). The remaining linebacker will be the A-gap player to the ball. If the RB blocked he can add to the pressure.

The clip below illustrated this coaching point:

BOB (Blitz Opposite the Back) Pressures:

Once offenses got clued to the Hokies adding to the back, they would work to cross their back in protection to eliminate the extra add on blitzer. So, when offenses would start to “scan” the back in protection by having him work opposite, “B.O.B.” pressures (Blitz Opposite the Back) principles were built in. The linebacker (either Mike or Backer) would be the blitzer while the other would play A gap to ball or add-on as an additional rusher and he may choose to swipe the front to the side of the pressure.

The clip below illustrated this coaching point:

The Impediment: RB’s Becoming Viable Pass Options/Mobile QB’s

When Bud Foster first came into the Big East in 1995 running backs had two jobs: run downhill and don’t fumble. Things have changed in the last 25 years. Running backs at the FBS level now are multi-purpose players who can not only stretch the field horizontally but can stretch it vertically as well. They are often recruited to be dual threat players in the run and pass game. In the ACC alone in 2019, his last year as a coordinator, opposing running backs accounted for over 180 receptions. This forced him to implement several adjustments in his base defense and pressure system to account for threats out of the backfield.

Mobile quarterbacks were also few and far between when he started his career. The Big East and ACC were stocked with pocket style signal-callers. In fact, there was one in his conference in 1995- Donovan McNabb at Syracuse. Yes, he was one of the best that ever played. But now several quarterbacks have the ability to break the pocket and extend plays. It’s forced him to completely change the way he’s evaluated quarterbacks. Prior assessment tools such as arm strength, the timing of the release, the level of his shoulders on throws and pre-snap indicators have been supplanted with measuring the QB’s ability to escape while keeping his eyes downfield. “We look at how well he throws on the run,” Bud told me. “Can he throw from hash to hash? What is his true skill set? You want to make sure you contain him. You may want to get some twists to get up in his face so he gets spooked. QB’s that can extend the pocket are very difficult to defend. If you spy on him these days then you’re giving up someone in coverage or in the rush.” The challenge lies in finding a defender with equal ability to match the skill set of the QB. Chances are that won’t be a defensive lineman. More often than not you’ll need two skill defenders to handle that responsibility. It’s something that Bud was forced to do when defending Notre Dame QB Ian Book in 2019.