"In G defense I can close my eyes and know how teams were going to block and manipulate us. We couldn’t protect the backside linebacker in gap runs."

- Bud Foster, former Defensive Coordinator, Virginia Tech University

By Mike Kuchar

Senior Research Manager/Co-Founder

X&O Labs

@MikeKKuchar

The Ideology: A Single Gap Control Mentality

Bud Foster defenses know how to get after the quarterback. In fact, since he arrived in Blacksburg in 1995, the Hokies have led all FBS programs in sacks (894) and sack yardage (-6,110). And while he realizes that the days of the 50 sack per year season tally has dissipated, he still works tirelessly to put less and less on the shoulders of the defensive ends in his system. It’s a far contrast from many defensive coaches who expect these players to handle multiple responsibilities in the run and pass game. For years in Blacksburg a defensive end’s job description was two parts: get off the ball and create havoc. And with the success of many under his tutelage- Jason Worilds, Darryl Tapp, Cornell Brown, and Corey Moore to name a few- who is to argue? Coach Foster built his G defense around spill principles in the run game, asking first level players to bend down the line of scrimmage to spill blocks so that linebackers can be free to make plays. This philosophy stayed true to keeping those precious linebackers free to flow to the ball, and came with first level defensive lineman playing single gap control in most situations. He never tinkered with the two-gap technique, mainly because he felt he didn’t have the type of personnel to do so. “You don’t see many defenses that can line up and play two-gap that can just man-handle people like Alabama can,” he said. “We couldn’t get those guys. We can play with smaller guys that are every bit as physical.” So, he had to create one on one situations that allowed players to play faster. And since most offenses work to manipulate edge defenders in the read game, it didn’t make sense to ask him to do multiple things. “Edge players are our most dynamic players,” he said. “You want them to be playmakers. Offenses continually try to negate speed players and manipulate them, so we try to find ways to allow them to play fast and attack the offense. If we slowed them down, it affected our pass rush. Instead, we turned them loose.”

The Impediment: Lack of Protection for Box LB’s in 11 Personnel Run Game

Back in 2015 when I last visited with Bud, he was enamored with the Bear defense, and for good reason. The Hokies had just come off a 35-21 win at 8th ranked Ohio State, where he used the Bear front exclusively to draw off double teams to hold the Buckeyes' potent run game to 108 yards on the ground, down from the 264 yards per game they averaged that season. The plan worked until the following season when OSU rushed for 359 yards in a redemption win. RB Ezekiel Elliot wasn’t a great matchup for the Mike linebacker (who would be?) and QB Cardale Jones was able to avoid the 5-6 man pressures to extend plays and just like that the Bear defense was shelved. But according to Bud, that outcome wasn’t the sole impetus that drew the change.

Part of the role of turning first level defenders loose was allowing them to be bend players and not read players. These were called “Free Calls,” in Bud’s system where the defensive end was able to bend down the line of scrimmage to play the first level of the option concept. It was an easy technique for first-level defenders that were able to get the ball spilled to the perimeter so that second and third-level defenders can run things down. It fit with the premise of the G defense because it got everything spilled. But the problem was the upfield natural movement of that defensive end allowed for offensive linemen to get angles on second level linebackers who were not able to get over the top of blocks in gap concepts. So, in a sense, the ball was getting spilled to grass.

The Adaptation: The 50 Defense

So, in 2017, Coach Foster went back into the lab and produced what he felt was the perfect hybrid between the Bear and his vaunted G defense. He called it his 50 defense.

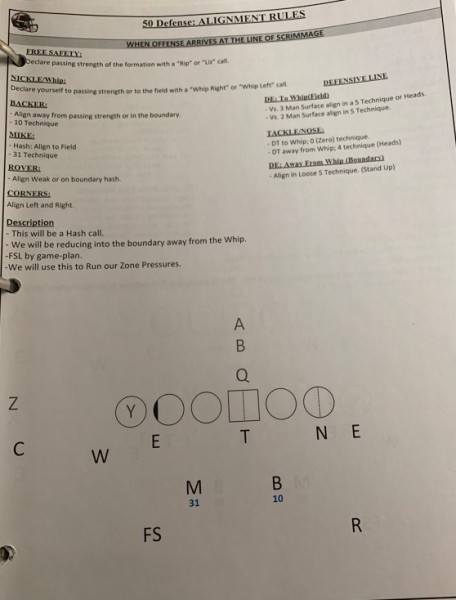

Without changing personnel, he tabbed what he called a “Bear” End who would be allowed to be in a standup position at the line of scrimmage. The other 5-technique defensive end would align with the Whip/Nickel, the Nose would reduce to a pure 0 technique, and the Tackle would play a 3-technique to the side of the “Bear End.”

The Bear End can be set to the following surfaces based on specific preferences:

- To the Boundary- This provided alley support to boundary corner in field zone pressures

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point:

- To the Field- This provided immediate support in any perimeter runs like jet sweep

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point:

- To the Back- This provided immediate mesh disruptions for speed options teams.

The clip below best illustrates this coaching point:

- Away from the Back- This provided immediate mesh disruption on dual options like power read.

- To the Tight End- This provided a better edge for outside runs

To get these protocols straightened out, the Bear End would align to the strength called by the Mike. The Mike would set the front to any of those possible scenarios above while the coverage would adjust accordingly. But if there were pressures called, the base rule was to have the Bear End align to the boundary or away from passing strength.

The 50 defense was something he wanted to use exclusively against the 11 personnel run game because the presence of a backside B gap responsible first level defender made it hard for linemen to get to the backside linebacker in run schemes. “You get two linebackers in the box and usually one of them is clean,” he told me. “It was a big help in defending spread gap schemes that we’re seeing now like counters.” According to Bud, it also allowed the field defensive end to play both the C and B gap in his “pop pinch” technique described below. The Mike linebacker was able to overlap concepts and run them down.