By Gordon Sammis with Mike Kuchar

Offensive Line Coach

University of Connecticut

Twitter: @CoachSammis

Everywhere Gordon Sammis has been, the wide zone has been his most efficient concept. A true Alex Gibbs disciple, Coach Sammis installed the wide zone at VMI, William and Mary, and now UCONN. And walking into the meeting rooms at Storrs it’s clear that offensive line culture is built off this concept. There is signage that reads loud and clear:

“If you can’t run outside zone, you can’t play here. If you don’t like outside zone you don’t belong here. If you don’t execute the outside zone, we won’t win here.”

“We are going to get our PHD in the wide zone play,” he says. “It’s the one run in my mind where I don’t necessarily need to block the box and be okay. It doesn’t matter who the quarterback is. He can be a runner or a statue because we will cut the backside guy free and our aiming point should help us win.”

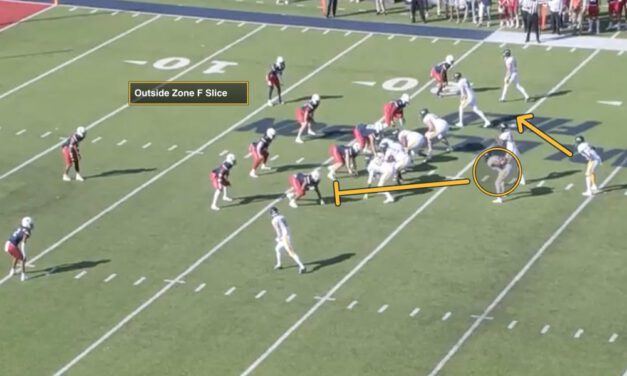

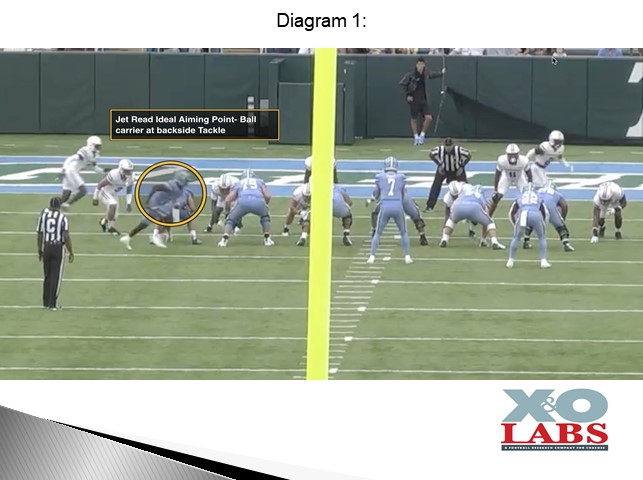

RB Landmarks:

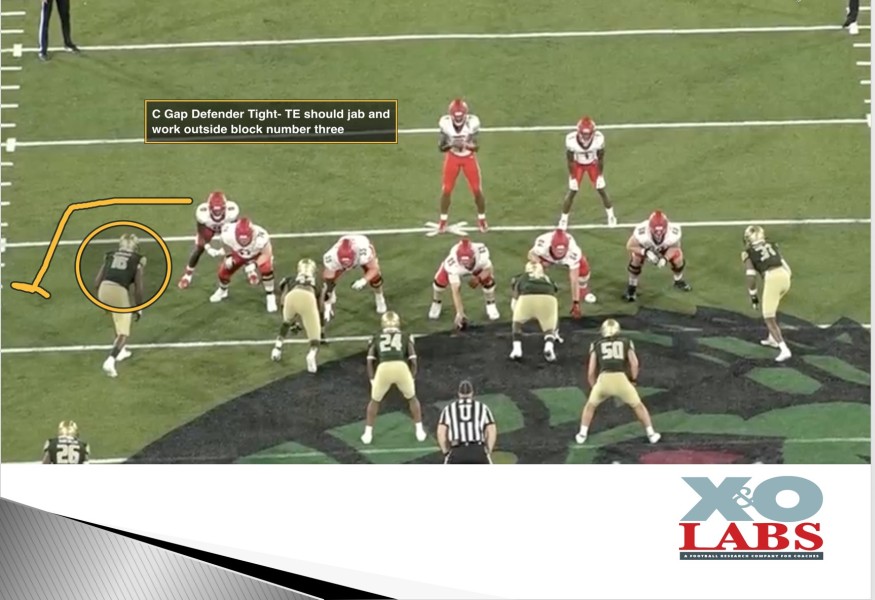

In true Alex Gibbs style, the play side tight end (or ghost tight end in a two-surface formation) is the aiming point for the ball carrier. And the emphasis is getting to the aiming point. “We talk about not losing ground with your feet because the back will get scared,” he said. “Once you get the ball start getting downhill right away and run the outside edge of the hole. We call it ‘riding the wave.’” The ball carrier still reads the number one (defensive end) to the number two (next adjacent defensive lineman inside) defender.

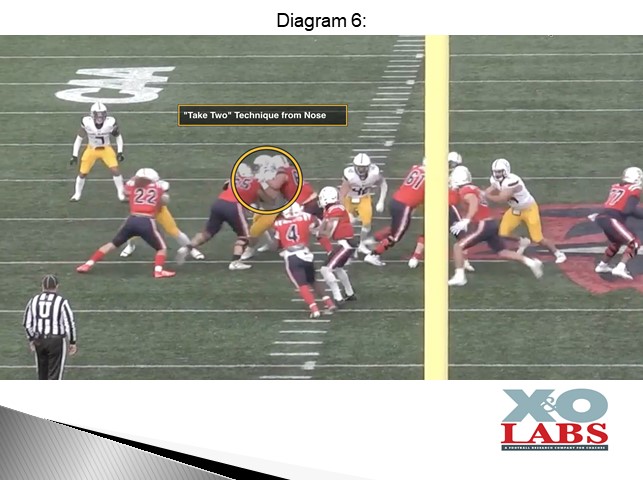

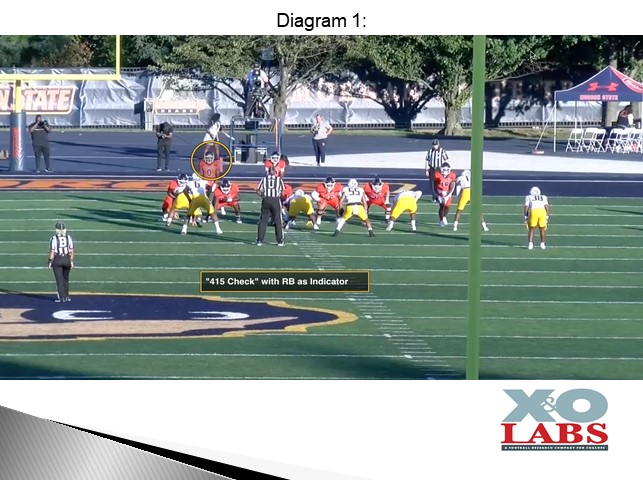

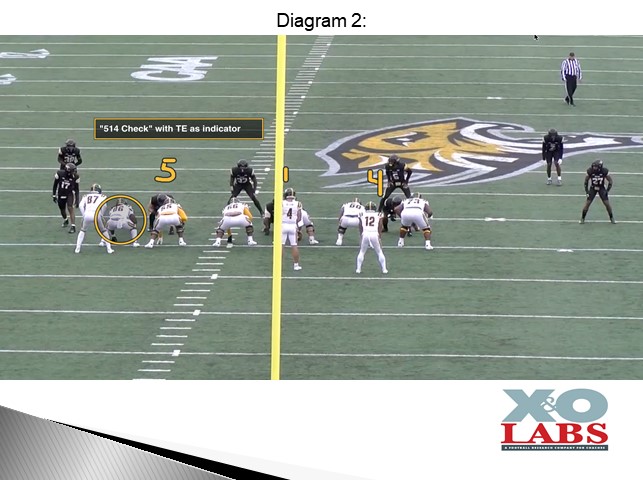

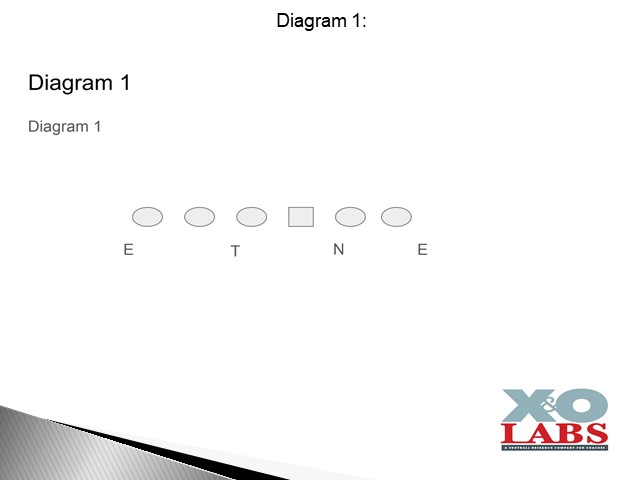

Simple Box Count System:

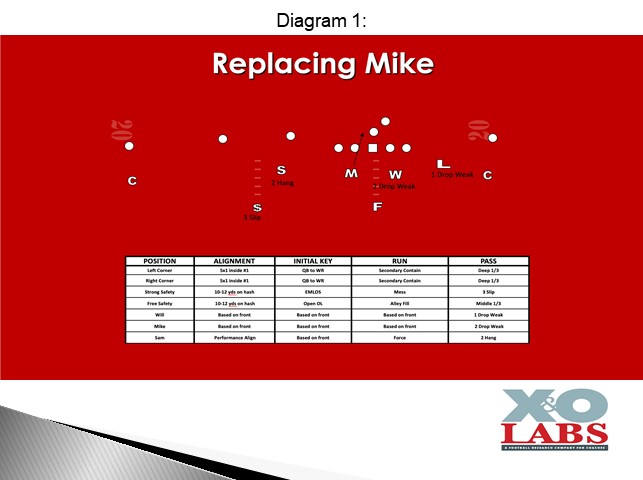

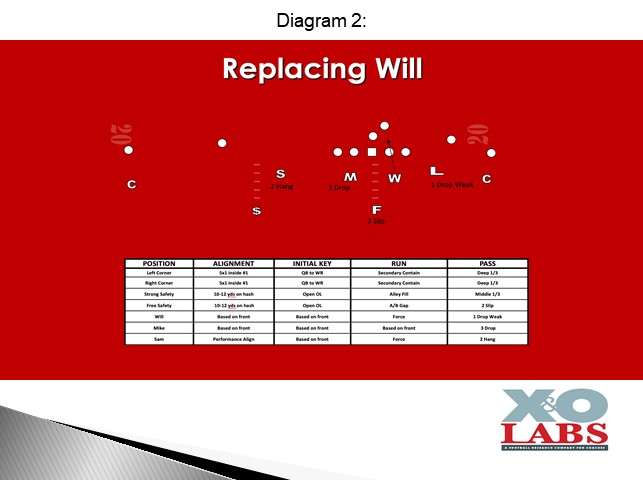

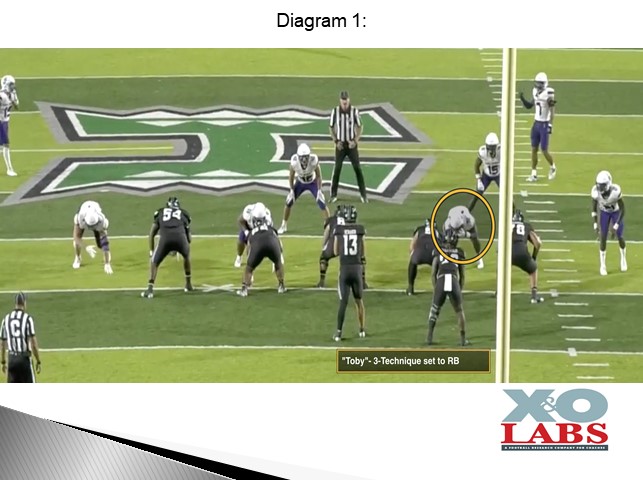

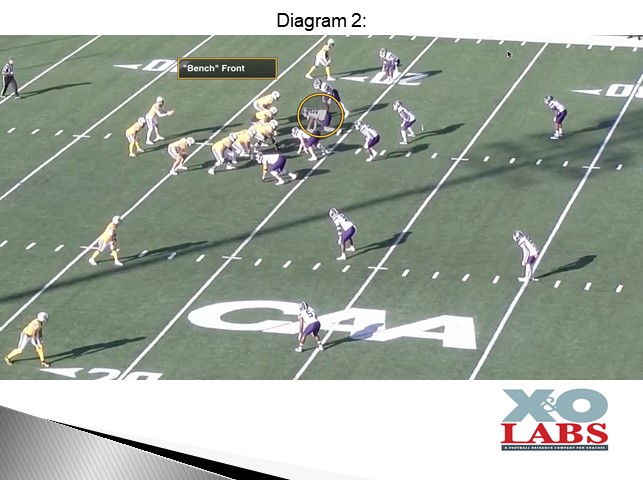

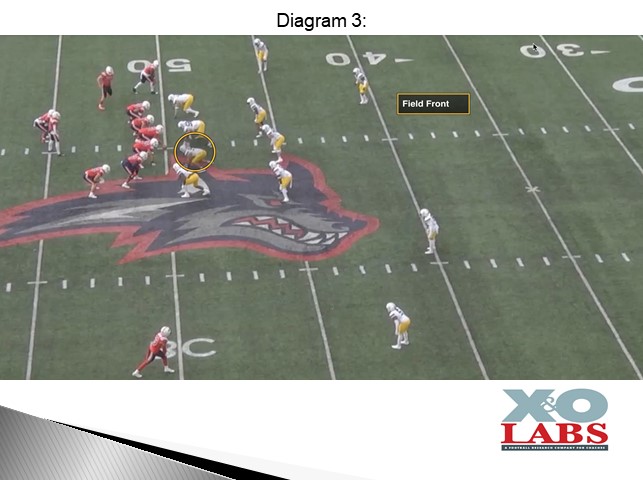

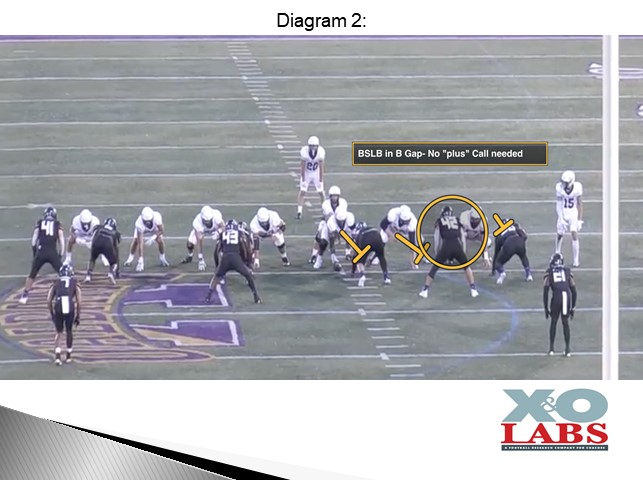

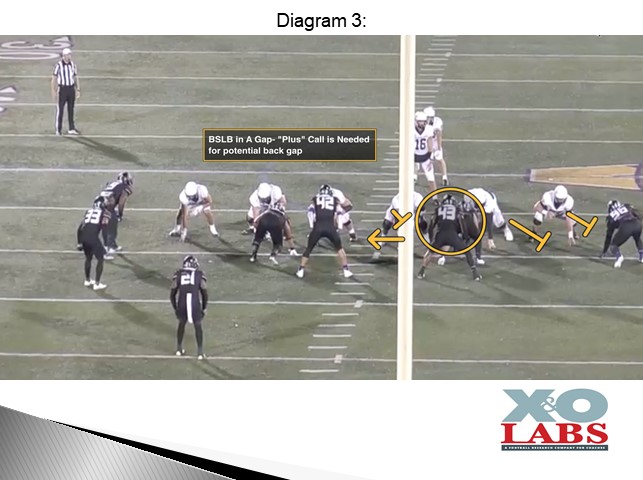

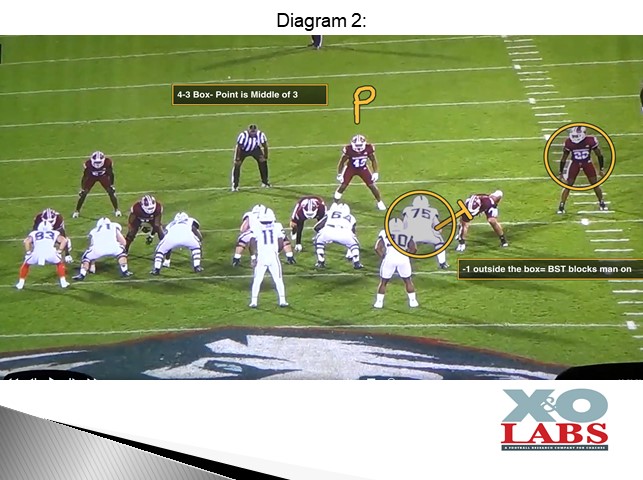

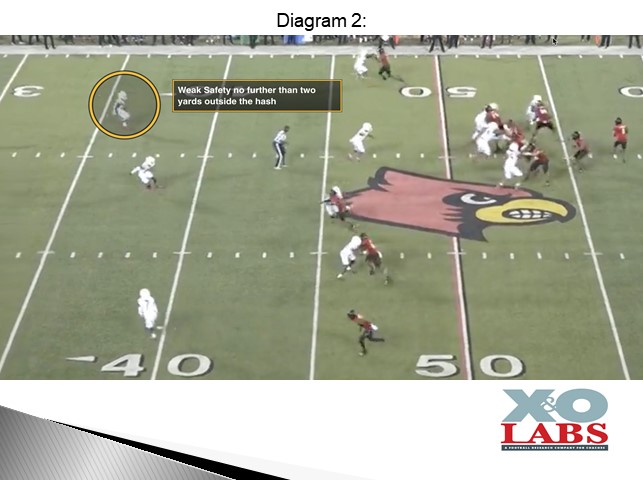

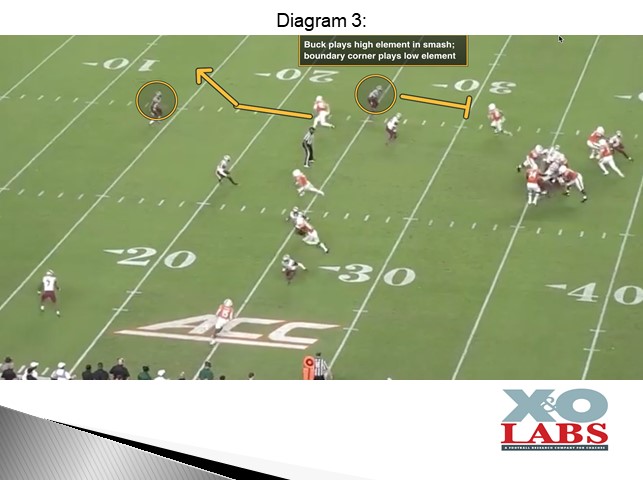

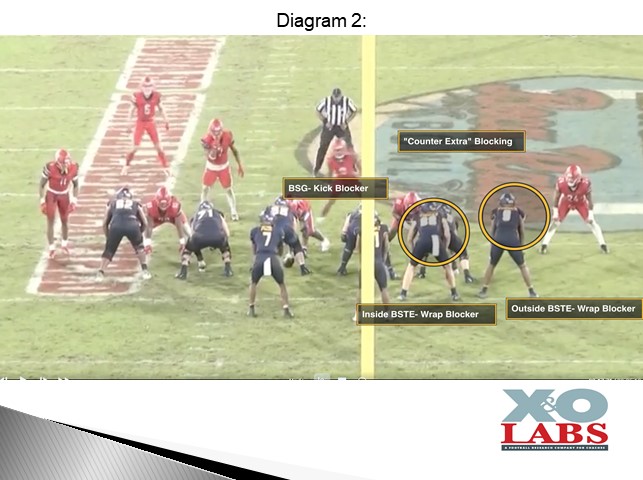

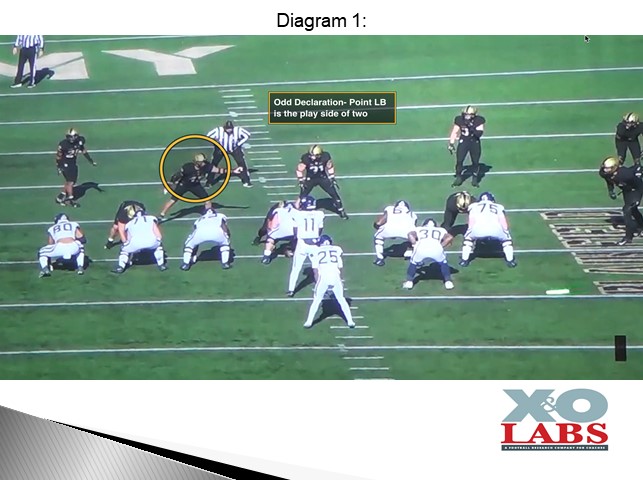

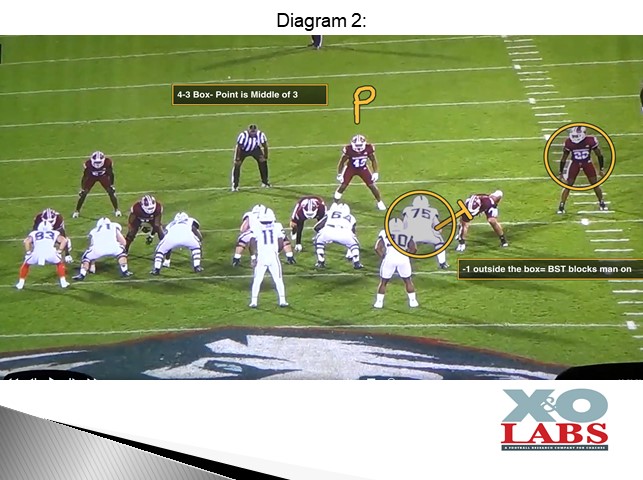

At UCONN, the emphasis in the scheme is blocking people, not gaps or areas. “We declare the front first and then everything off of the backers in the box,” he says. Once the front is declared it’s all about the plus-one backer or the minus-one backer and everyone knows their rules from there. The Mike is always declared as the play side of a two-linebacker box and the middle of a three-linebacker box. Anytime there is a plus one to the play side it’s considered the closed side, and the tight end is asked to handle that defender. “We care about the point but we are working as independent contractors from the front side to the backside,” he said. “Backside guys know that we can never make a combination call to Mike linebacker. If the Mike linebacker is backside, we should be in a man situation.”

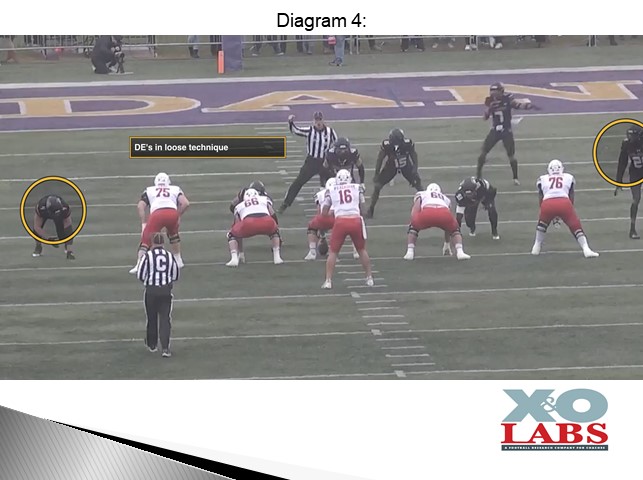

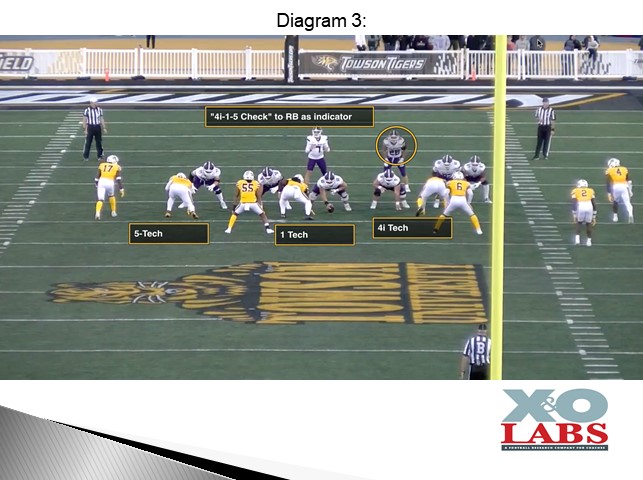

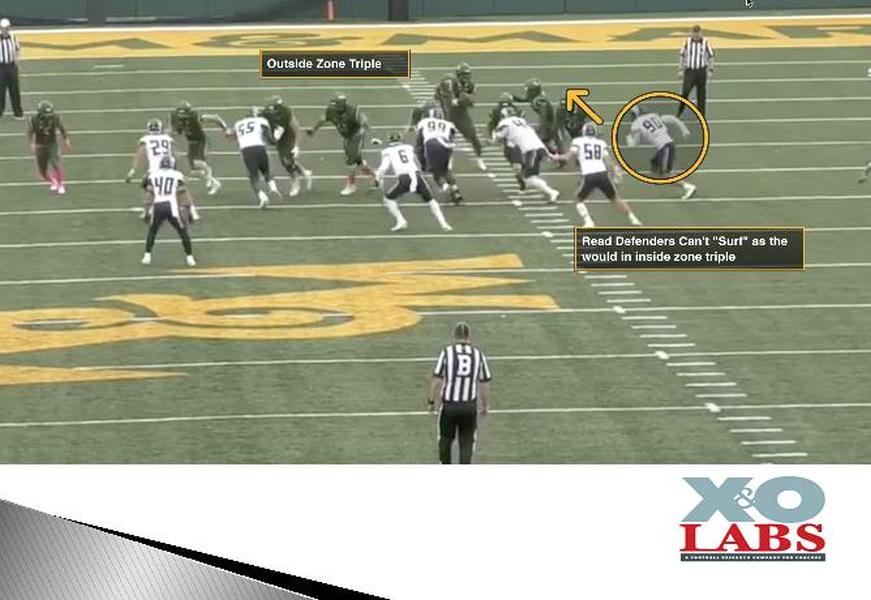

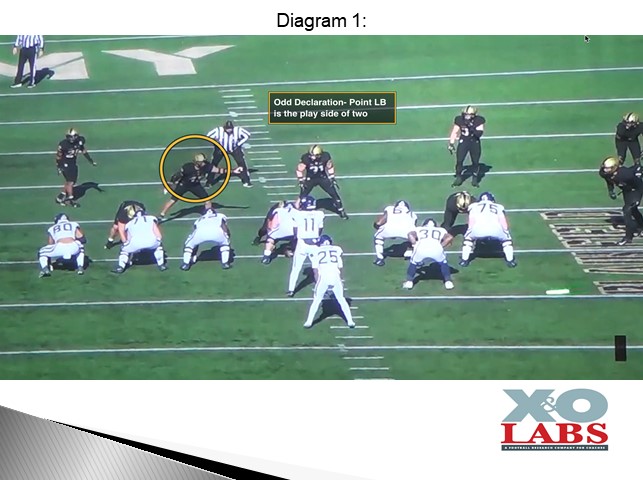

Methodologies in Attacking Odd Looks:

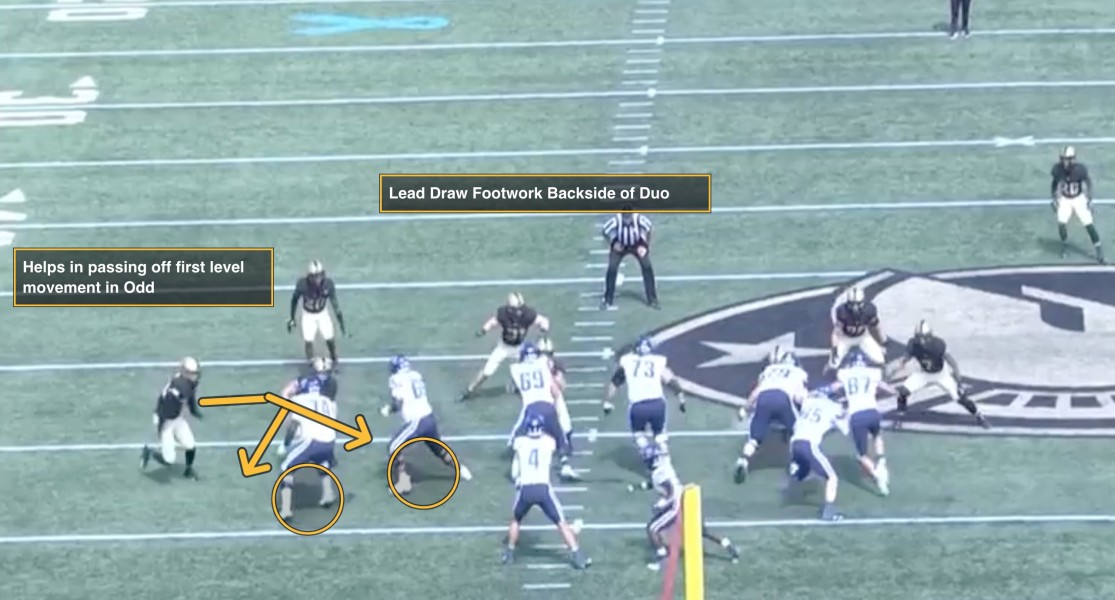

UCONN has created different names for the wide zone, particularly against Odd, particularly on the backside where the Tackle had to alert the tight end whether to fan or not. “We had to get that related to the Tackle in a tempo system and we had more missed assignments on the backside than anything else,” said Coach Sammis. This is why the point is on the front side against Odd, because that linebacker is the play side of two.

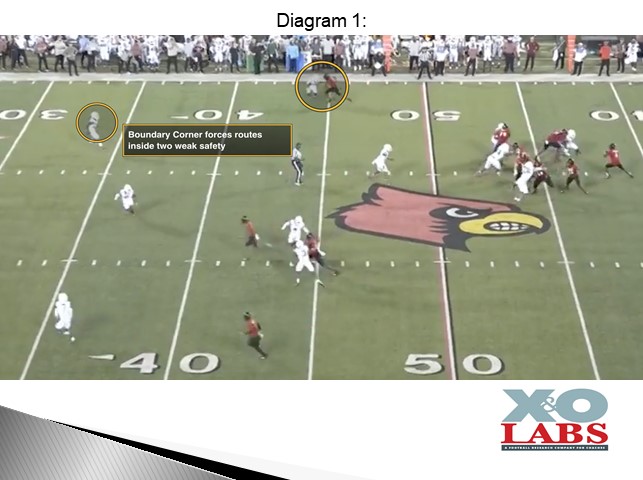

If the backside tackle has man on or man outside, so they don’t sift and anytime the minus one is wide, they will just man block the backside. “It helps against defenses to the boundary because we got leverage on the backside,” said Coach Sammis. “If the Tackle was to the closed side he knew he had to sift. If it was open-sided, he could full reach. He didn’t need to hear the call. He just knew.”

This is why the outside zone became a great boundary-side run against Odd looks because defenses put their smaller defenders to the boundary, who may be a hybrid linebacker or rush defensive end, which allowed UCONN to get their bigger blockers on these types.

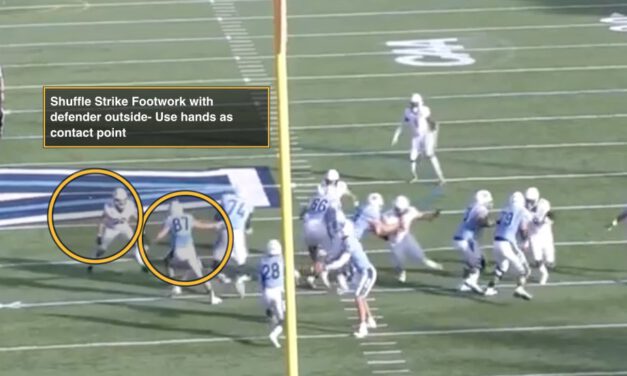

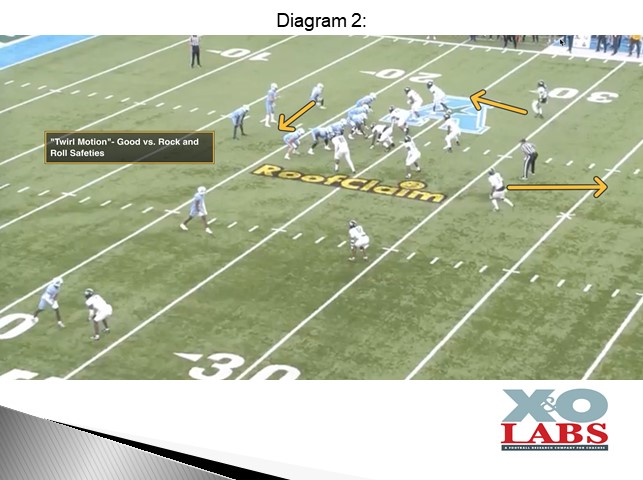

“No Fly (Motion)” Zone:

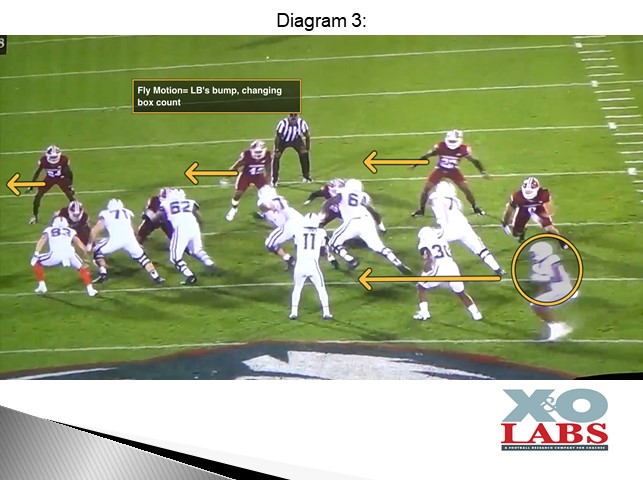

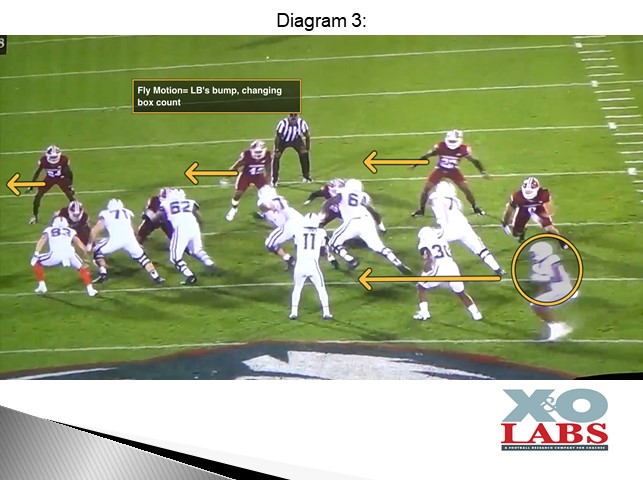

According to Coach Sammis, the issue with jet motions is that it presents a four count to the open side of the formation. Second-level players bump and the box count gets construed. “You’re presenting a picture and then you’re taking a blocker away at the point of attack,” Coach Sammis told us. “If they start rolling 3 strong or 3 buzz you’re going to be short a blocker.

We no longer can block a hat for a hat. Again, we don’t want to double to an area. We want to go to people. If that motion causes us issues with LB’s falling into the box play side, I don’t want to live in that world that week. I want them to get the safeties to rock and roll. Then we can bring that fly motion and run it the other way. We don’t want the minus one to become the Mike. We don’t want to screw with the box.”

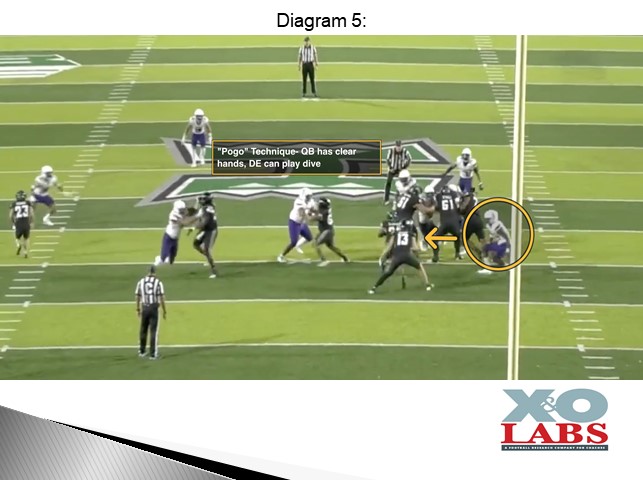

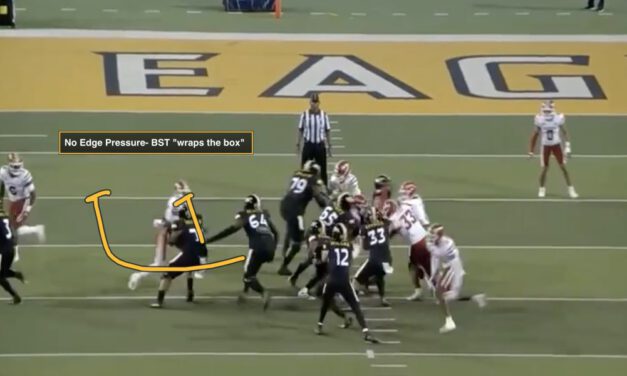

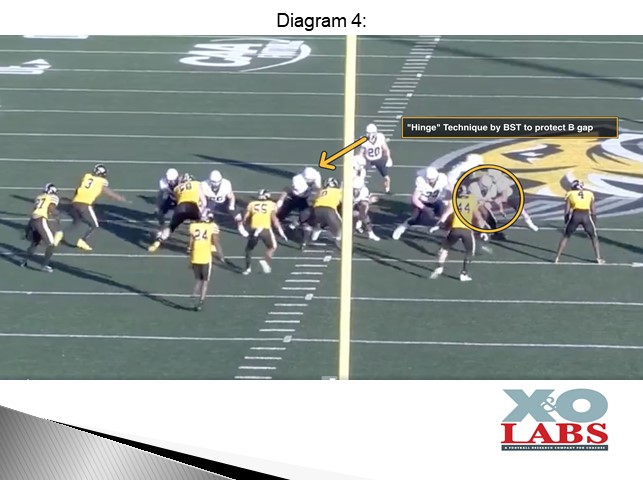

Backside Blocking:

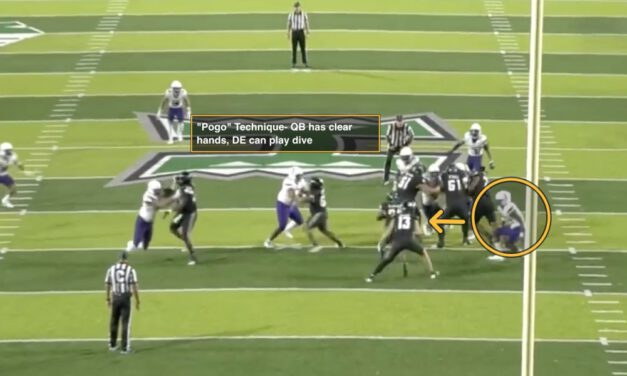

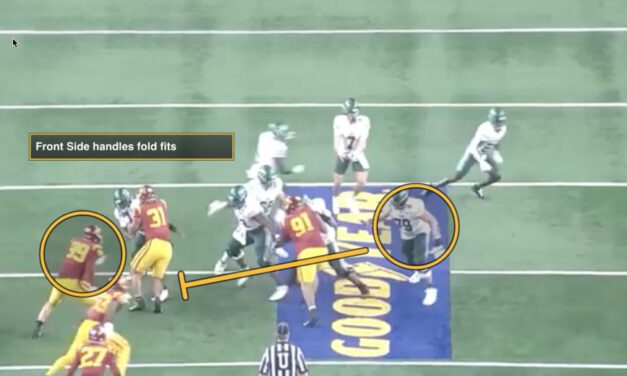

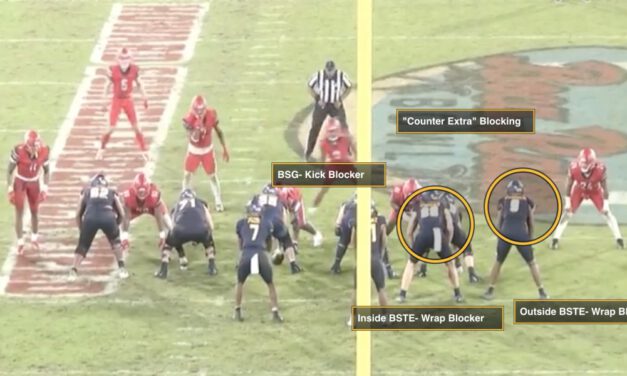

Before getting into how UCONN controls the backside of the wide zone scheme, it’s important to note that they no longer treat the frontside and backside the same. They used to but wound up torquing defenders right into the ball against ball carriers who were reading one to two on the play side. Now, it’s purely cutoff blocks only.

Now we will get into the various tags Coach Sammis and his staff will utilize to control the backside of wide zone.